Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Thursday, 13 August 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By R.D.R. Jayanpathi

|

Ministry of Finance

|

Sri Lanka relies on debt to finance much of its public spending. Until recent tax increases (in 2016) almost half of all government expenditure to provide services, pay government salaries and pensions was funded by debt. Since 2007 when the first international sovereign bond was issued, an increasing proportion of this debt was foreign commercial debt.

Commercial debt is relatively hassle-free but short-term and expensive.

Multilateral agencies (World Bank, ADB) on the other hand require detailed feasibility studies prior to funding and then require constant monitoring and evaluation of the project. Thus the loan application and administration process for multilateral debt is time consuming, cumbersome and complex, requiring technical, financial, environmental, social and risk evaluations.

These are the “strings” that the Government complains that come attached to multilateral loans. The advantage of these procedures is that it reduces the likelihood of a “white elephant” project. The country has a “herd” of white elephant projects from cricket stadiums in the jungles to empty airports but none of these were financed by multilateral loans.

Multilateral loans are also much cheaper than commercial debt; between 2005-19 loans from the ADB cost an average 2.62%, World Bank an average of 1.38% compared to 6.61% for commercial debt.

Despite the obvious advantages of multilateral debt the government exhibits a clear preference for commercial debt which has grown from zero (in 2007) to 50% of all foreign debt.

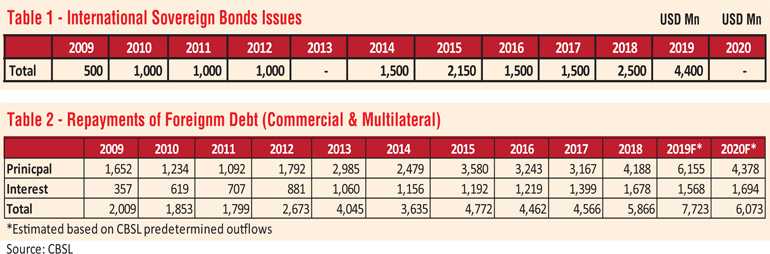

A surge of optimism followed the end of the war and borrowings accelerated post-2010, supported by favourable international trends; low interest rates and a rising investor appetite for emerging market debt. From 2012 onwards repayments on older commercial debts started to kick in (see table 1). The burden of the repayment on all foreign loans is seen in table 2.

Total repayments in 2020 (of capital and interest) amounts to an estimated $ 6 b (capital of $ 4.3 b, estimated interest of $ 1.7 b). Repayments on the international sovereign bonds are around $ 2 b, Sri Lanka Development Bonds (SDB) around $ 1 b and the rest are from multilateral sources.

Sri Lanka’s growing indebtedness is worrying but is it becoming unsustainable?

A debt trap is a situation is where new debt is needed to pay old debts also known as rollover because the country lacks income to pay the old debt she has taken. The growing ratio of debt to GDP is an indicator that the debt burden is getting out of control.

Fitch Ratings forecasts a debt-to-GDP ratio of 94% in 2020 (above the ‘B’ rating median of 66%) and is expected to rise further in 2021. Another indicator of debt sustainability is the ratio of debt to government revenue. Fitch says the ratio for Sri Lanka is close to 900%, far above the ‘B’ median of 350%.

Now conditions have weakened globally and Sri Lanka’s economy has stagnated. After a brief spurt post-war (2010-2012) when GDP growth averaged 8.5% it then dropped in the next six years (2013-18, average 4.13%) as the principal drivers (post-war construction and underutilised capacity) were exhausted. The Easter attacks of 2019 saw growth slump to 2.3% in 2019. Now with the pandemic the World Bank expects GDP to contract by 3.2% in 2020 and remain flat at zero percent

next year.

The outlook on debt is precarious. As Fitch warns:

“Sri Lanka’s recent three-year Extended Fund Facility with the IMF expired in early June after going off track last year when a new government introduced tax cuts that were contrary to the programme’s revenue-based consolidation strategy…. Sri Lanka’s debt servicing obligations over 2021-2025 are substantial, amounting to an average of $ 4.3 billion per year. We cited a further increase in external funding stress, reflected in a narrowing of funding options and weaker refinancing capacity, threatening Sri Lanka’s ability to meet external debt repayments”.

The solution

Needless to say, after reading the above, the Sri Lankan economy is at precarious state and putting import controls to save the rupee like what Dr. N.M. Perera did during 1972 to ’77 simply won’t work as during that time Sri Lanka never had foreign debt problem or at least very little of it to worry about and now it’s completely

different.

So, what is the way out? We must form new partnerships with our old friends such as Japan and the European Union. We need to increase our exports, get their technological and human resource skills development inputs and get funding for projects that generate revenue, employment and value addition to the economy.

Sri Lanka also needs to restructure its debt obligation. We simply pay too high interest on loans taken under the last two decades.