Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday, 29 March 2018 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sri Lanka suffers a staggering 850+ recorded deaths a year by drowning, falling short quite dismally in delivering on health and safety obligations in the water. In fact, the country has the 12th highest drowning rate out of 61 countries analysed in the 2014 World Health Organisation Global Report on Drowning and the 10th highest when compared with 35 Low and Middle Income Countries.

Sri Lanka suffers a staggering 850+ recorded deaths a year by drowning, falling short quite dismally in delivering on health and safety obligations in the water. In fact, the country has the 12th highest drowning rate out of 61 countries analysed in the 2014 World Health Organisation Global Report on Drowning and the 10th highest when compared with 35 Low and Middle Income Countries.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that recorded deaths are understated due to poor data surveillance on drowning. There is also no centralised analysis of serious injuries related to near drowning incidents – for example where people are hospitalised with sometimes long-term impairment. Drowning is not limited to the accidents you may hear at beaches, but encompasses all inland national governing entity waterways and disasters such as floods.

A lack of leadership and a national plan are keeping these numbers high – despite untiring efforts by Sri Lanka Life Saving (SLLS), dedicated lifesaving teams in the forces and a small pool of grassroots organisations and government agents.

In addition to not addressing drowning deaths, there is a significant missed opportunity in not taking a strategic and planned approach to how Sri Lanka can maximise the tourism and economic value from our beaches and waterways. The benefits of prioritising water safety start with helping save lives and quickly leads to increased tourism, employment creation and small to medium size enterprise development.

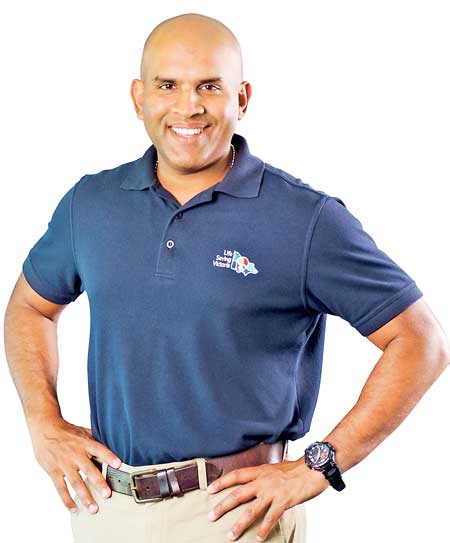

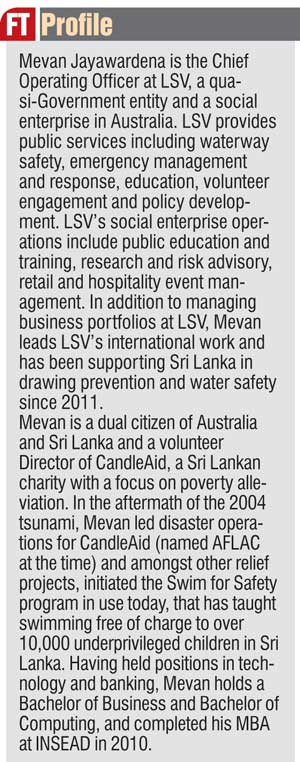

“The main thing that is lacking is leadership. We need to strategically prioritise drowning prevention and water safety, develop a national plan and charge an entity with the responsibility for delivering that plan,” asserts Mevan Jayawardena, who is the COO of LSV, an Australian organisation in the forefront of international best practice in this field that has supported Sri Lanka over the past 6 years.

The lack of a sense of urgency in addressing Sri Lanka’s second highest cause of death is alarming.

While there has been some progress, there needs to be a much more concerted effort, driven by the humanitarian need and the potential for economic upside.

Following are excerpts of an interview with Jayawardena on water safety, Sri Lanka’s lifesaving operations, recommendations of the proposed national plan, action that can be taken to make our waters safe, and the culture of volunteerism in Sri Lanka:

By Marianne David

Q: Sri Lanka has a very high drowning rate. What are the key steps that need to be taken to arrest this situation, create awareness and highlight the dangers?

A: The occurrence of drowning is multifaceted, it can happen at beaches, lakes, rivers, damns, pools, flood situations, open wells and buckets of water. It can happen to anyone in any age group. Therefore, the steps that need to be taken to address are multifaceted.

In a simplified way, the steps in the next year are: deploying prioritised lifesaving services at location and times at frequently visited by people, e.g. beaches on Sundays; making sure people who visit waterways are made aware of how to be safe – for example going to places where lifesaving services are present, taking something that floats with them and avoiding currents; getting the media active as a major supporter and enabler – the more news the better from both a messaging and prioritising perspective; developing a data surveillance system to understand clearly and in a timely manner where people access waterways, where people drown or nearly drown and what they were doing when this happened; and getting a multifaceted national plan in place that is endorsed by the highest levels and an entity in place to deliver on this plan.

The next two to three years is all about implementing the national plan in a prioritised manner. The plan will have elements of regulations and guidelines that need to come into place – for example requiring swimming pool operators to follow standardised safety practices such as having trained lifeguards and securing appropriate rescue equipment – not the prehistoric fibre glass rings on walls. It is extremely important to get early runs on the board for economic value. For example, uplifting the Sri Lanka’s ratings by major foreign tour operators on safety measures at beaches and swimming pools to encourage larger groups travel from Europe.

The most important strategy in the longer term is making sure every child leaving primary school attains a minimum level of basic swimming competency and understanding of how to be safety in the water. We don’t need swimming pools for this, there are plenty of open waterways, such as lakes, dams and rivers, that can be used for children to learn swimming. Achieving this outcome will bring about the behavioural change to address drowning and better utilise the natural water assets in the country. It will also lead to better health outcomes for children.

Q: What is the current state of lifesaving operations in Sri Lanka?

A: There has been major progress in the last seven years from an operational ground-up perspective. Examples of progress include the ability for SLLS to train lifesaving locally people to international standards, reaching thousands of people through education programs, deployment of first level lifesaving services by the SLLS volunteers and the forces (Police, Coast Guard, Navy, Air Force, Army and Civil Security Department). Another major step has been the pilot of the ‘Swim for Safety’ program across the country in open water locations. Through this program, children are taught basic swimming in 12 lessons – please find Swim for Safety Sri Lanka on Facebook to see it for yourself.

From a the top-down perspective, in terms of a strategic national approach to drowning prevention and water safety, we have been running in the same spot for the last two years. We have drafted a strategic approach in terms of what needs to be done, but lagging in formalising this and commencing the implementation through a dedicated entity.

The last major action I am aware of from a strategic perspective was a five-day multi-sectorial workshop conducted in July 2017. A number of stakeholders were convened, by Ministry of Disaster Management and the Disaster Management Centre. The stakeholders, from education, the forces, police, tourism and health validate the draft plan and the prioritised actions. The outcome of the workshop was a report comprising prioritised recommendations linked to the draft plan.

Q: Could you outline the recommendations from the last workshop?

A: 1.Finalise the National Action Plan and establish a national governing entity for drowning prevention and water safety. The role of the national governing entity would be to implement the National Action Plan and monitor progress, assigning steering and technical committees to decentralise the solutions. The entity should be linked to provincial, district and local governments, bringing together national and district stakeholders. There isn’t an issue of not knowing what to do and there is no shortage of expertise locally and internationally. An entity for water safety is crucial as we can only get so far with a fragmented approach. The entity does not need many people, we need a good head and a couple of operators. The entity must have a mandate to push the water safety agenda nationally.

2.Develop and operate a National Drowning Data Surveillance System to look at where people drown, what they were doing when they drowned, age, where they reside and so on. When we published the drowning report in 2014, we were years behind in terms of the data we received. The data we get does not include the proper information relating to a drowning, about where exactly the person drowned, what they were doing prior to drowning and where the person lived. That is important as well. The drowning might be in Mount Lavinia but the person could be coming from somewhere else so the interventions need to match that. We plan to release the second drowning report in September this year and it will have updated statistics and information about all the lifesaving coverage that we provide, broken down by provinces.

3.Formulate a risk profile for beaches and waterways for Sri Lanka. For example, if you take Mount Lavinia beach, there are certain risks there based on the formation of the beach, the bays and so on. That risk is compounded by demographic factors, the number of people who go there, etc. Taking natural and usage burden into consideration, for every water location there is an element of risk you can define. For example, the risk is high at water bodies in Anuradhapura during pilgrimage time. A risk profile will inform what areas are at risk during which times of the year and can deploy lifesaving personnel accordingly. It is also important to have a water safety app to inform the public and tourists where to go. The feeder to the water safe app is information from the risk profile and where lifesaving services are provided.

4.Develop and implement a National ‘Swim for Safety’ program. Every child has to learn to float for a minute, how to swim 25 metres in any stroke and how to be safe in water. We have a proven model for this which does not even need a pool; we can train anywhere in any water body. How do you make this available for every child? Through the schools. We have the people to train. If you take the forces network alone, there are plenty of people. What is the gap? Someone to strategically plan all this at a policy level. The best thing to do is to put this program in the school curriculum.

5.Establish National Beach and Pool Safety Guidelines.

Q: How can tourism maximise on economic benefits through safe water-related activities?

A: Recommendation six addresses maximising economic benefits for tourism through safe water-related activities. There is a simple five-point plan (prioritise, standardise, resource, promote and evaluate).

First point is to prioritise water safety where the tourism sector makes a concerted effort to do better in water safety, understanding the benefits and the missed opportunities.

Second point is to standardise water safety. Lifeguards should be trained to the same standards by the same authority, which covers the risk management chain. Training, uniforms, rescue crafts and pool equipment – all this has to be standardised.

Third point is to resources water safety. There is no point having the standards without people and financial resources to implement them. One of the biggest issues is whether we can get personnel locally. We absolutely can. You can easily train someone to be a pool lifeguard. People are not an issue. In terms of cost, a lifeguard can earn around Rs. 40,000 a month. A security guard earns Rs. 30,000 on average. It is an affordable cost. When it comes to equipment, it must be visible and recognised, which gives an image of safety.

Fourth point is to promote water safety. At a national level, there can be a country level marketing campaign about safe enjoyment of water. There can be an app that promotes where the safe waterways are. As a hotel chain, if you have done steps one to three, you can talk to top travel groups and show the steps you have taken to ensure safety in the water. You must integrate everything you do here into your marketing and promotion strategy.

Fifth point is to evaluate water safety. We need to be able to measure the value that we are getting from this water safety, which will help sustain steps 1 to 4.

Q: If a hotel wants to make its beach and pool safe, what immediate action can it take – what is the checklist?

A: Firstly they would invite SLLS and the process starts off with a risk assessment. Second is the output, an implementation plan that will state how many lifeguards and what equipment are needed. SLLS can provide the lifeguards as well. Three is implementation. The implementation plan also makes some marketing recommendations. SLLS has the ability to provide these services. Four is promoting it, which the hotel has to do.

Q: How long has LSV been working with SL and what does the relationship entail?

A: LSV has been working in Sri Lanka since 2011. It started off with capacity building for core lifesaving services – training the local personnel, giving them resources and educating them. Then in 2014 it moved into identifying the problem in depth with the reporting side of things. After that it has moved more to helping set up the National Strategic Framework.

Amongst all that, every year we have a group of young people travelling from Australia to gain experience in international work in a different work environment and they actually learn from going to Sri Lanka.

Q: What would you say are Sri Lanka’s strengths in relation to its beaches and lifesaving and what are its weaknesses?

A: The strengths, the most obvious ones, are beautiful beaches, natural environment, warm water all year round and accessibility in terms of roads and so on. There are natural strengths and also the people. Natural disasters have shown that Sri Lankans are naturally resilient and caring. There is an innate need to help someone. If you take the core of lifesaving, it is to help someone. I think the natural instinct people in a country like Sri Lanka as opposed to more Westernised countries lends itself more to lifesaving.

Weaknesses is the complete lack of understanding of the problem and the opportunity; the problem being people not learning to swim and the high rate of drowning and the opportunity is the fact that we are not utilising all these natural benefits we have and an understanding of how to actually strategise towards this end.

Q: What role can hotels play in developing lifesaving and making beaches safer?

A: The role of the hotel is to firstly identify there is an economic benefit from better utilising the water assets. Then secondly is implementing strategies to actually reap that benefit. If they are doing those two things, they are going to be engaging the local population and creating more visitation and participation and economic activity.

Q:What role can schools play?

A: The role of schools is that for anyone to get in the water, they must learn the basics. Schools must make it a priority for children to learn basic swimming and water safety so that they have a foundation, an understanding from a young age on how to use water, enjoy water and gain some value from it.

Q: Given the high drowning rate, what can we do immediately to address it in terms of preventative action?

A: If you look at how you are going to have the biggest impact, it is to have a public awareness campaign so that people are educated about the issue and you actually encourage the right behaviour. That could be simple things like, ‘if you are going to a beach, here’s a rip current, here’s what it looks like,’ give a sense of how to identify what it looks like and how to avoid it. Then the importance of learning to swim – implementing a proven model such as ‘Swim for Safety’ in schools. Thirdly, making sure that the national priority is driven through a national plan and a national entity.

Q: The culture of volunteerism propels lifesaving in Australia. What is the strategy Sri Lanka should adopt in setting up a volunteer service and encouraging volunteers?

A: The most important thing to understand is that it has been done in Sri Lanka. We have the two schools, Ananda College and Nalanda College, which have lifesaving teams that patrol at Mt. Lavinia beach. They have been doing that for years, so how do you adopt that model in other schools? That’s the starting point.

Secondly, there are lifesaving clubs that people can join and volunteer. The key point is to understand what is there and the models that have been trialled already so that we can have maybe five other schools doing it.

Then the third point from a Government point of view is recognising the value that these volunteers are creating and putting in reward, recognition and resource programs to enable them to flourish. For example, if there is a team of volunteers doing lifesaving in Matara, recognise them, give them some equipment, and provide the structure so they can flourish.

Q: What is your key message to the public on staying safe in the water?

A: My first message is go and enjoy the water. Second message is to find a safe way to enjoy by either going to places with lifesaving services, going with people who know or having something that floats with you. Thirdly, find a way to learn basic swimming and how to be safe in water.