Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Thursday, 15 October 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

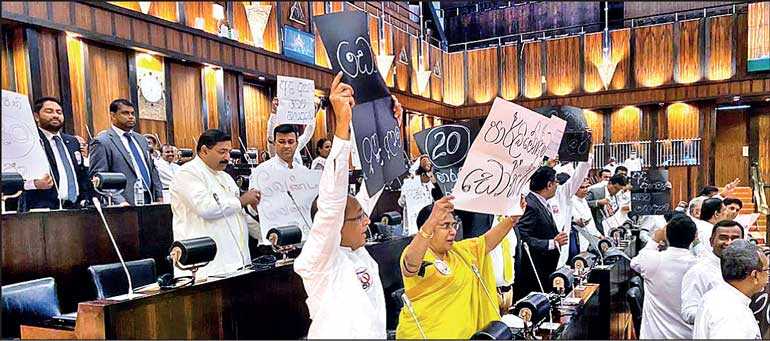

The Women and Media Collective has expressed concern over the impact the 20th Amendment to the Constitution in its present form will have on the fabric of democracy of the country, particularly in relation to the implications on media freedom, the right to information, the separation of powers, the plight of independent commissions, accountability and corruption and the restrictions placed on Fundamental Rights

The Women and Media Collective as a women’s organisation engaged in advocating social justice and human rights, is concerned over the impact the 20th Amendment (20A) to the Constitution in its present form will have on the fabric of democracy of the country.

Among other provisions in 20A we are particularly disturbed by the implications on media freedom, the right to information, the separation of powers, the plight of independent commissions, accountability and corruption and the restrictions placed on Fundamental Rights.

Free media and the right to information

The proposed 20A introduces a duty on all media institutions to comply with any guidelines issued to them by the Elections Commission in respect of the holding of any election or Referendum (clause 20(3) of 20A). We are concerned by any indication of State control over media and the consequences on the access to information during a critical period for exercising franchise.

The operationality of the Right to Information mechanism is at risk by its exclusion from clause 6 of 20A. The Right to Information Act requires appointments to the Commission to be made on the recommendation of the Constitutional Council. The Parliamentary Council that replaces the Constitutional Council, in the proposed amendment, has not been empowered to make these appointments.

As a fundamental right and crucial element of modern democratic societies, access to information must be safeguarded. This mechanism was widely used since its enactment, and therefore potential restrictions to access and availability of information is regressive and should be condemned.

Separation of powers

The separation of powers is a fundamental ingredient of democratic governance. It enables for each branch of government to function independently. At the same time a system of checks and balances are put in place to prevent absolute power being concentrated in one arm of government. Through the proposed 20A these core values are blurred rendering unfettered power to the Executive office of the President and other organs of Government under the President’s rule.

Dissolution of Parliament – Clause 14 of 20A

Under the proposed amendment, the President has the power to dissolve Parliament at any time except in limited situations and must wait one year from the date of such General Election only if the election was held consequent upon a dissolution of Parliament by the President.

Additionally, Members of Parliament can by resolution of a simple majority request the President to dissolve Parliament at any time. This renders the Legislature at the mercy of the President and weakens the Parliament of the day. It is also troubling that the mandate of the people is being compromised through these provisions.

Independence of the Judiciary – Clauses 6, 23 and 25 of 20A

Under the proposed 20A the President may appoint and remove the Chief Justice and Judges of the Supreme Court, President and Judges of the Court of Appeal and members of the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) without the approval from the Parliamentary Council. The President can also make such appointments without reference to their seniority or judicial experience. These amendments directly compromise the independence of the Judiciary.

As guardians of the Constitution and an important check on other organs of Government the independence of the Judiciary must be considered sacrosanct.

Independent Commissions – Clause 6 of 20A

The Parliamentary Council (PC) which replaces the Constitutional Council (CC) does not in any way reflect good governance and its powers in the democratic process are made negligible by this amendment. Members of the PC will only be Members of Parliament and will no longer include independent members of eminence and integrity.

Unlike the CC, the PC can only make observations which have no binding effect on the President. The President therefore has unfettered power to make appointments to; the Election Commission, the Public Service Commission, the National Police Commission, the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka, the Commission to Investigate Allegations of Bribery or Corruption, the Finance Commission, the Delimitation Commission, the Attorney-General, the Auditor-General, the Parliamentary Commissioner for Administration (Ombudsman) and the Secretary-General of Parliament, in addition to the judicial appointments mentioned above.

All these bodies have been set in place as regulatory mechanisms to ensure transparency, accountability and justice. By solely concentrating power in the President to make these key appointments, the very independence of the entities that keep persons in power accountable is compromised.

Unless Parliament enacts additional laws, three key bodies within the transitional justice framework namely the Right to Information Commission, the Office of Missing Persons and the Office of Reparations could be rendered non-operational by their exclusion from 20A (clause 6 of the 20A).

Under 20A, the PC that replaces the CC has not been empowered to consider these appointments. Since their establishment in 2018 these three bodies have enabled members of the public and especially women to access rights and justice. We are therefore deeply concerned by the Government’s intentions to ignore access to justice provisions.

Accountability and anti-corruption

The Election Commission is restricted from issuing directions on any matter relating to the public service (clause 20 (2) of 20A) which will prevent them from taking action against the misuse of public property during elections. A large number of election related offences are connected to the misuse of public property which serve to benefit those in power.

In addition, the National Procurement Commission has been abolished (clause 55 of 20A), impairing an essential monitoring mechanism on public spending. Such clauses depict the absolute disregard of the drafters of this amendment to the misappropriation of public finances.

The proposed 20A restricts the powers of the Auditor General and the Audit Service Commission (clauses 32-40 of 20A). The Office of the Auditor General will no longer be required to subject the Secretary to the President and the Office of the Secretary to the Prime Minister to an audit, meaning that the financial transactions of the leaders of the country will not be transparent.

Further, clause 40 (1) of 20A omits the requirement under Article 154 (1) of the Constitution to audit “companies registered or deemed to be registered under the Companies Act No. 7 of 2007 in which the Government or a public corporation or local authority holds fifty per centum or more of the shares of that company”.

This effectively means that companies, relating to airlines and power for example, that have been making loses to the Government will no longer be open to scrutiny. The constitutional recognition of the Commission to Investigate Allegations of Bribery and Corruption has been repealed and a government in future can abolish the Commission altogether by a simple majority (clause 54 of 20A). The powers of the Commission to initiate investigations on its own accord have also been taken away. These amendments expose the Government to corruption and removes important elements of accountability that should be part of governance processes.

Citizens’ right to be heard

The proposed 20A repeals the citizen’s right to file Fundamental Rights applications against executive decisions of the President (clause 5 of 20A). Taking away the citizen’s right to hold their elected President responsible for his executive actions severely undermines the progressive democratic right through which recent landmark cases have stayed the course of political whim.

The case concerning the premature dissolution of Parliament and the case concerning arbitrary pardoning of persons on death row are examples of citizens challenging executive decisions. In addition, any Bill certified by the Cabinet of Ministers as “urgent in the national interest” is not required to be published in the gazette (clause 27 of 20A). This process completely evades the public’s right to know the contents of a bill and challenge it if necessary.

The President shall refer the bill to the Supreme Court to decide on the Constitutionality of the Bill within a maximum period of only 72 hours. The restriction placed on time, runs the risk of the law-making process being unduly rushed and thereby affecting the quality of judicial review.

Duties of the President

The proposed 20A takes away the obligation on the President to ensure that the Constitution is respected and upheld (clause 3 of 20A).

The fact that the leader of the country will not specifically commit to upholding the values enshrined in its Constitution is a serious cause for concern. It poses a danger that provisions, such as fundamental rights, protecting the environment and protecting the rights of vulnerable groups that are meant to inform governance for the establishment of a just and free society could be open to interpretation.

Clause 3 also removes the duty of the President to promote national reconciliation and integration. In light of post war rebuilding efforts and the recent violent extremist movements, it is alarming that the country’s leadership should not be guided by notions of national reconciliation and integration in the best interest of all citizens. Constitutional reform requires careful consideration through an inclusive and engaged process.

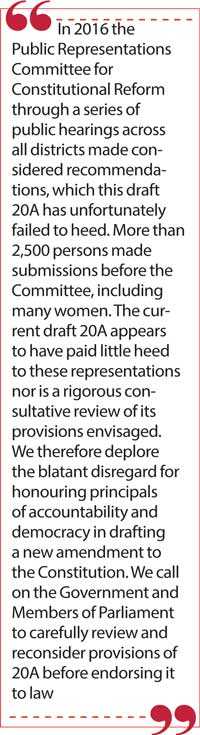

In 2016 the Public Representations Committee for Constitutional Reform through a series of public hearings across all districts made considered recommendations, which this draft 20A has unfortunately failed to heed. More than 2,500 persons made submissions before the Committee, including many women. The current draft 20A appears to have paid little heed to these representations nor is a rigorous consultative review of its provisions envisaged.

We therefore deplore the blatant disregard for honouring principals of accountability and democracy in drafting a new amendment to the Constitution. We call on the Government and Members of Parliament to carefully review and reconsider provisions of 20A before endorsing it to law.