Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Saturday, 8 December 2018 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By S.S. Selvanayagam

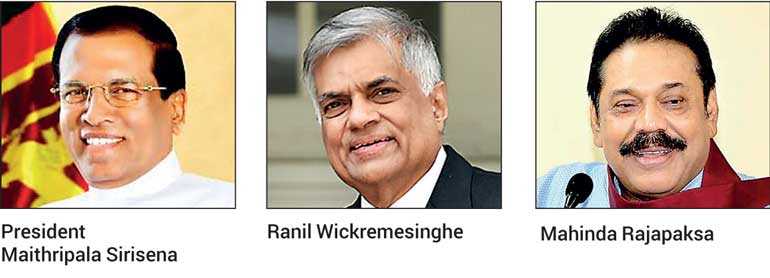

The Supreme Court yesterday concluded the hearing of multiple Fundamental Rights petitions against the move to dissolve the Parliament by President Maithripala Sirisena as well as several intervening petitions, and extended the Interim Order against the Executive action till the judgment is delivered.

The seven-member Supreme Court Bench, over the past four days, listened to submissions connected to the 10 Fundamental Rights petitions against Sirisena’s move as well as eight intervening petitions.

“Judgment was reserved with date to be notified to Counsels later,” legal sources told the Daily FT. Pending the delivery of judgment, the Interim Order against President Sirisena’s move was extended.

Previously, the Interim Order was originally issued until 7 December (yesterday) and on Thursday (6 December), it was extended till today.

The Supreme Court Bench comprised of Chief Justice Nalin Perera, Justices Buwaneka Aluwihare, Sisira J. de Abrew, Priyantha Jayawardena, Prasanna S. Jayawardena, Vijith K. Malalgoda, and Murdu Fernando.

The 10 Fundamental Rights petitions were after the President moved to dissolve Parliament on 9 November following instability after he, on 26 October, removed the sitting Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe and appointed nemesis Mahinda Rajapaksa instead. Following litigation by MPs, political parties and civil society, a three-member Supreme Court Bench, on 13 November, issued a Stay Order against the Gazette dissolving Parliament.

President’s Counsel K. Kanag Iswaran yesterday, countering the arguments of the Respondents and the Intervenient Petitioners, underlined that the immunity conferred on the Executive President is only on his person not his action or acts.

Counsel Kanag Iswaran, appearing for R. Sampanthan, made his reply to the Respondents’ submission before the Supreme Court Bench.

Counsel Kanag Iswaran, continuing his reply, said he does not propose to deal with the jungle of arguments of single instances put forward by the various Respondents, on account of the time constraints.

He stated that President’s Counsel Sanjeewa Jayawardene and the other Counsels of similar persuasion have sought to submit to Court their interpretations of the relevant constitutional provisions on the basis of the Sinhala text of the Constitution.

He said that, not being competent in that language, he has requested President’s Counsel Thila Marapana and the other Counsels for the Petitioners to deal with that aspect. He informed Court that they assure him that the Sinhala version is in no way different to the English version. He claims he knows for a fact that the Tamil version is no different.

He stated that, therefore, he propose to only the Attorney General with a response in respect of his submissions, principally on the question of the jurisdiction of Supreme Court to hear and determine his Petition on the two grounds urged by the Attorney General, namely:

“The provisions of Article 38 (2) provide a specific mechanism ‘for the Supreme Court to exercise jurisdiction over allegations of, intentional violations of the Constitution, misconduct or abuse of power by the President’;

“Dissolution of Parliament by the President does not constitute ‘Executive or Administrative action’, falling within the purview of Article 126 of the Constitution; Ouster of Jurisdiction.”

He said that where the objection premised on Article 38 (2) is concerned, it is clear that the said objection is based on the supposition that Article 38 (2) operates as an ouster of Articles 17 and 126 vis-à-vis the Fundamental Rights Jurisdiction of the Supreme Court.

He contended that one section of the Constitution cannot oust another section of the Constitution.

The constitutional jurisdiction of Supreme Court to grant relief for the infringement of Fundamental Rights by Executive or Administrative action cannot be ousted in the absence of a constitutionally valid derogation from that jurisdiction, he pinpointed.

Ex facie the Constitution, such an ouster cannot be validly asserted, he emphasised.

He brought to cognisance that a total ouster is found in the interpretation section of the Constitution, namely, Article 154J (2) – Public Security.

He stated that the said interpretation section reads: “A Proclamation under the Public Security Ordinance or the law for the time being relating to public security, shall be conclusive for all purposes and shall not be questioned in any Court, and no Court or Tribunal shall inquire into, or pronounce on, or in any manner call in question, such Proclamation, the grounds for the making thereof, or the existence of those grounds or any direction given under this Article.”

He submitted that the Article 170, defining a judicial officer as ‘judicial officer’ means any person who holds office as a Judge of the Supreme Court or a Judge of the Court of Appeal; any Judge of the High Court or any Judge, presiding officer or member of any other Court of First Instance, Tribunal or institution created and established for the administration of Justice or for the adjudication of any labour or other dispute but does not include a person who performs arbitral functions or a public officer whose principal duty or duties is or are not the performance of functions of a judicial nature. No court or Tribunal or institution shall have jurisdiction to determine the question whether a person is a judicial officer within the meaning of the Constitution but such question shall be determined by the Judicial Service Commission, whose decision thereon shall be final and conclusive. No act of such person or proceeding held before such person, prior to such determination, shall be deemed to be invalid by reason of such determination.”

He stated that the above ouster clauses seek to even exclude the Fundamental Rights jurisdiction of the Supreme Court.

He prevailed that, therefore, Article 38 is no ouster at all.

He submitted that the Petitioner is well within his rights to have invoked Articles 17 and 126 of the Constitution, because it is an acknowledged principle of law that there is no justification in law for holding that only one of the available remedies can be availed of and that the other consequently stands extinguished, nor can it be contended that the aggrieved party be confined to only one remedy.

He further said that passionate presentations were made on the question of the sovereignty of the people and the franchise of the people and the obligation of the President to heed that and for the Supreme Court to take note of that fact.

He mentioned in passing that the sovereignty of the people and who the depositories of that are is to be seen in Article 4 and that Article 4 (a) provides that the sovereign Legislative power of the people is in the Parliament and that Article 4 (b) provides that the sovereign Executive power of the people is in the President.

He maintained that, therefore, under the Constitution, the President cannot interfere with the Legislature except as strictly provided by the Constitution.

The dissolution of the Legislature must, therefore, strictly be in terms of the Constitution and the President is not a monarch, he too is a creature of the Constitution. It is settled law that the official acts of the President constitute ‘Executive’ actions, he said.

He submitted that the concept of ‘Executive and Administrative’ action is much wider than Executive power.

He stated the Petitioners invoked a right given to them under Article 17 read with Article 126, read together with the proviso to Article 35 (1).

In terms of the proviso ‘anything done or omitted to be done by the President in his official capacity’ are in fact ‘Executive or Administrative’ acts in terms of Article 17 and, therefore, the reference to Article 126 is made in the said proviso, he stressed.

The contention of the Attorney General that the President’s act is not ‘Executive or Administrative’ action is in terms of the Constitution wholly untenable, he contended.

The issue of dissolution which the Supreme Court is called upon to decide is not justiciable because it is a political question, he claimed.

He recollected that another interesting, if not intriguing, submission was about a ‘Legislative-driven process’ and an ‘Executive-driven process’.

This description, curiously, lays emphasis only on the driver and forgets the vehicle, which is Article 70 (1), he said.

Without the vehicle, the driver cannot move. Whether Legislative-driven or Executive-driven, you need to have a Proclamation, he stated.

The functionaries of the three wings – namely, the Legislature, the Executive and the Judiciary – derive their authority and jurisdiction from the Constitution. The Constitution is the fundamental document that provides for constitutionalism, constitutional governance and also sets out morality, norms and values which are inhered in various Articles and sometimes decipherable from the constitutional silence, he said.

Its inherent dynamism makes it organic and therefore, the concept of constitutional sovereignty is sacrosanct. It is extremely sacred as the authorities get their powers from the Constitution and nowhere else. It is the source that is the supremacy of the Constitution, he highlighted.

He reminded that passionate speeches had been made, mostly political, warning the Supreme Court of the impending dangers and the like if the dissolution is not upheld. It went as far as calling the challenge to the dissolution as terrorism, he said.

He recalled the words of Dr. Ambedkar: “I feel that the Constitution is workable; it is flexible and it is strong enough to hold the country together both in peace time and in war time. Indeed, if I may say so, if things go wrong under the new Constitution, the reason will not be that we had a bad Constitution. What we will have to say is that man was vile.”

There were 10 Fundamental Rights petitions filed against the declaration of dissolution of Parliament by the President. Five sought to intervene to counter the main petitions.

The petitions seek a declaration that the proclamation of dissolving Parliament infringes upon the Fundamental Rights.

They ask the Court for a declaration that the decisions and/or directions in the proclamation are null and void ab initio (ineffective from the beginning) and of no force or effect in law.

The petitions were filed by Kabir Hashim and Akila Viraj Kariyawasam of UNP, Lal Wijenayake of United Left Front, CPA, Member of the Election Commission Prof. Ratnajeevan H. Hoole, Attorney-at-Law G. C. T. Perera, Sri Lanka Muslim Congress, All Ceylon Makkal Congress, MP Mano Ganesan.

K. Kanag Iswaran PC, Thilak Marapana PC, Dr. Jayampathi Wickremaratne PC, M. A. Sumanthiran PC, Viran Corea, Ikram Mohamed PC, J. C. Weliamuna PC, Ronald Perera PC, Hisbullah Hijaz, and Suren Fernando appeared for the Petitioners.

Gamini Marapane PC with Nalin Marapane, Sanjeeva Jayawardane PC, and Ali Sabry PC appeared for the intervenient Petitioners opposing the main petitions.