Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Friday, 22 December 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

In his 1930 poem W. H. Auden issued this challenge: “Let us honour if we can / the vertical man / though we value none / but the horizontal one/”. He meant that humanity worships powerful living fellow creatures and forgets the dull dead.

In his 1930 poem W. H. Auden issued this challenge: “Let us honour if we can / the vertical man / though we value none / but the horizontal one/”. He meant that humanity worships powerful living fellow creatures and forgets the dull dead.

But we Sri Lankans are one better than Homo erectus superior of the Western civilisation our poet critiqued: for we honour our ancestors among other ghosts of the past. This is neither good nor bad; but thinking makes it so. If practised by mindless cretins who resurrect the shade of Dutugemunu rather than the spirit of (let us not say it) some more peaceable monarch intent on tranquillity and serenity for all his subjects, more so!

A few of us Easterners inverted Auden’s ask last week. It was the birth centenary of one of Sri Lanka’s brighter suns. Albeit one born in the West… at Minehead, in Somerset, on December 16, 1917. Of course it is Srilankabhimanya Arthur Clarke to whom I refer. And while beautiful Ceylon (as it was known when this mindful adventurer first looked on our fair shores) was less pusillanimous than the Crown of Great Britain in bestowing its accolades, it is not of Sir Arthur’s life or death that I sing. That is left to bards and beloveds. Since my theme is honouring the horizontal man, it is our own space-age prophet’s island-vision I wish to hymn today…

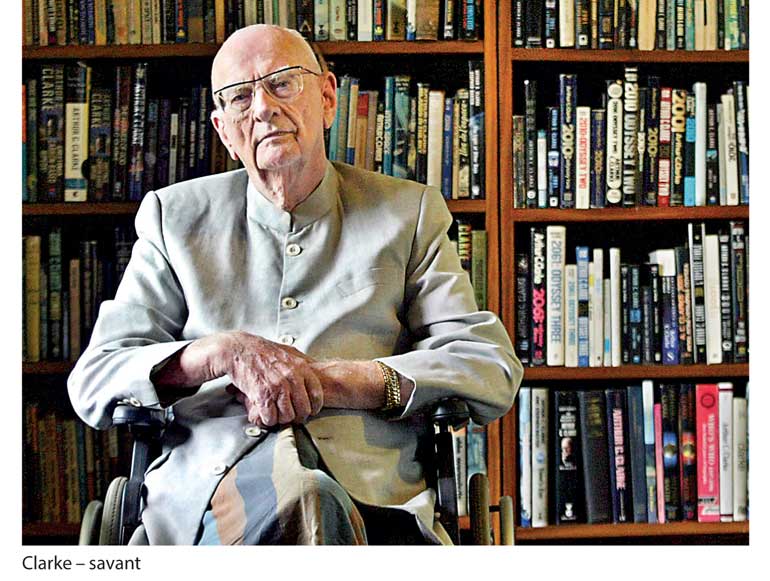

Not his scientific prophecies or technological predictions. But rather his personal wish-list for the land of his adoption. And perhaps the best way would be to hear our late great savant’s words for ourselves. At least as expressed to the people of his island-paradise over a decade ago. So here are Sir Arthur’s words.

When asked – in the aftermath of the tsunami – whether there was an opportunity to rebuild Sri Lanka along model-nation lines, he said: “Yes, every disaster and every calamity can be turned into an opportunity. As Sri Lankans struggle to come to terms with the shared grief and multiple impacts of this tragedy, they need to be aware of this potential. The first priority is to provide shelter and relief. But we must also address the long-term issues of better preparedness, effective warning systems, and disaster mitigation. The best tribute we can pay to all those who perished or suffered in this disaster is to heed the powerful lessons it offers us. Nature has spoken loud and clear, and we ignore it at our peril.”

After being told our nation was in crisis long before that tsunami hit (this month, four days from now, 13 years ago), Clarke rejoined: “I think not just Sri Lanka, but the whole world, is facing multiple crises – in terms of global security, safeguarding democracy, and meeting unlimited human aspirations with the limited energy and resources of our planet.” He added: “Here, in Sri Lanka, I have been unhappy witness to bitter armed conflict for over two decades, which has consumed twice as many lives as did the tsunami and blighted the future of millions more. Peace in Sri Lanka has been my number one wish for many years – I can only hope that the lashing from the seas will finally convince everyone of the complete futility of war and territorial disputes.”

We never heeded Mother Nature’s giving of notice to our nasty island-race. Nor did we hear Clarke and aspire to his tangential orbit in treating the tsunami as an opportunity for reconciliation. With that said, the honorary Sri Lankan expressed far more optimism about our prospects even then.

In a message broadcast over local television only a few days before the devastation of 26 December 2014, he said: “We should not allow the primitive forces of territoriality and aggression to rules our minds and shape our actions. If we do, all our material progress and economic growth will amount to nothing … I have always been an optimist, and I still remain optimistic that Sri Lanka will achieve a lasting peace.”

Well, we have peace now. Whether it will be durable and just is open to the winds of the future. But those volatile fumes of territoriality and aggression still seem to rule our minds and shape our actions.

Nor was Clarke caught short on ideas when he was challenged on what convinced him that Sri Lanka could redevelop itself (say along the lines of Singapore): “My vision in the next 50 years is inevitably shaped by what I have seen and experienced in the past five decades. We must exploit our comparative advantages – such as the high literacy and technical dexterity of our people; and the geographical location and medium size of our island. In a nutshell, Sri Lankans should not just work hard, but work smart in the global marketplace.”

He was keen that we evolve our own business and technical models. Clarke noted that during his half-century association with Sri Lanka, the island’s human population had almost doubled – and that managing this expansion would be one of the country’s “most formidable challenges”. In a nice turn on words he asserted that “the biggest challenge” would be – in terms of human health and welfare – “not so much to add years to life, but to add life to years”. But with the SAITM issue and other related striking issues in the medical and healthcare sectors clouding the horizon, the spectre of a moribund lifelessness looms large for our ageing demographic.

Politics was always on the table, even in a tête-à-tête ostensibly about science and technology. Indeed, the two enjoyed synchronous orbits in Clarke’s philosophical mandala: “Democracy needs to be customised and updated to suit modern-day realities as well as the new possibilities achieved by technological advancement. As the rapidly globalising world tries to eradicate poverty and improve living standards for all, the need for ensuring accountability in government – at local, provincial, and central levels – is an urgent priority.”

Perhaps, on the eve of Good Governance’s third anniversary, with transparency westering and promises slipping slowly over the horizon of island forgetfulness, even more urgent but increasingly less-prioritised?

A decade before the Arab Spring, Arthur C. Clarke saw how technology could give social media the status of a Fifth Estate: “Around the world, people typically respond to bad governance by rejecting governments at elections, or occasionally by overthrowing corrupt or despotic regimes through mass agitation. But there is now a realisation that this is not sufficient. The solution must lie in not just participating in elections or revolutions, but in constantly engaging governments and keeping the pressure on them to govern well…”

Told you so, folks. Some of us heard him. With a prime example being manthri.lk – perhaps other visionaries will follow suit, and maybe other modes of keeping government accountable will be en vogue sooner than later in the new year.

Clarke continues to speak into our context from beyond the cosmos’ further shores: “This relatively new approach involves the careful gathering of data, its systematic analysis, and knowledge-based engagement and negotiation with elected and other public officials. Crucial to this process is accessing and using critical information – about budgets, expenditure, excesses, corruption, performance, etc.”

The incumbent administration’s accomplishments in this regard – at least in theory – have to be acknowledged, even lauded, especially in the context for the fear-driven and rumour-ridden approach of the previous regime. In practice, journalists and civil society have far to go in tapping into the potential of RTI among other salutary breakthroughs – lest the bureaucracy rest on laurels they never won.

Ever the global visionary, Clarke was a prophet with a savvy approach to even a people-oriented mode of government: “The new breed of ‘citizen voice’ is thus about using information in a way that leads to positive change. In the emerging knowledge-based society, citizens are increasingly using knowledge as a pivotal tool to improve governance, use common property resources and manage public funds collected through taxation or borrowed from international financial institutions. We in Sri Lanka need to be aware of these trends and adapt the relevant ones.”

Asked by LMD what his aspirations were for the land where he had lived more than half his adult life were, Clarke replied: “I have seen my adopted homeland advance in various ways, but sometimes it has taken wrong turns. If we have the humility to learn from past mistakes, the next half-century can be far better than the last. I can only hope that we learn these lessons quickly and apply them resolutely.”

Let us honour if we can this horizontal man – though we seem to value none but the vertical one.

Let Clarke have the penultimate word…

“Lasting and tangible peace will be crucial, and I say this advisedly. In my youth I lived through the worst and most devastating of all wars in history. That enables me to feel the anguish of this once-peaceful nation caught in a prolonged conflict from which it is still struggling to extricate itself. I am optimistic that the land which has shown tremendous resilience over the centuries, and practised a rare type of tolerance, could still return to normalcy – although we should ensure that the grounds for conflict are eliminated forever … Peace is not a condition granted or secured by agreements. It is a state of mind that we all need to cultivate.”

Indeed. Neither guaranteed by constitutional reform nor enforceable by government fiat, no matter how good… Perhaps the pity of the matter may still well be that our prophet is not honoured in his own country or his adoptive and obviously much-loved homeland.

(A senior journalist, the writer is a former Editor of LMD. In May 2005, he interviewed Sir Arthur C. Clarke in LMD in what was later known to be one of his last long-interviews.)