Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday, 1 February 2019 00:20 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Much has been made of it. If you haven’t heard about CPI 2018, you’re probably living under a rock. And if you don’t want to see what creepy-crawlies dwell there alongside a pure in heart you, don’t pick it – the rock, or CPI 2018 – up.

But for those of us who like to know, the latest edition of the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) makes fascinating – if disappointing – reading. For those of us who follow Sri Lanka’s progress – or otherwise – on it, it’s an essential insight into how well we’re doing overall (we’re not). And if Transparency International’s rankings can be taken at face value, our island-nation has miles to go before we sleep.

It’s probably because many promises have been made – on the campaign trail and in parliament among other corridors of power – that we have yet to keep. For one: to bring sundry culprits from a previous regime to book in a transparent manner. For another: to ensure that the introduction of good governance into the administrative milieu would keep present powers accountable. For posterity: to drive the reforms agenda whereby the seeds of a new political culture would be sown in notoriously hard soil.

By the way

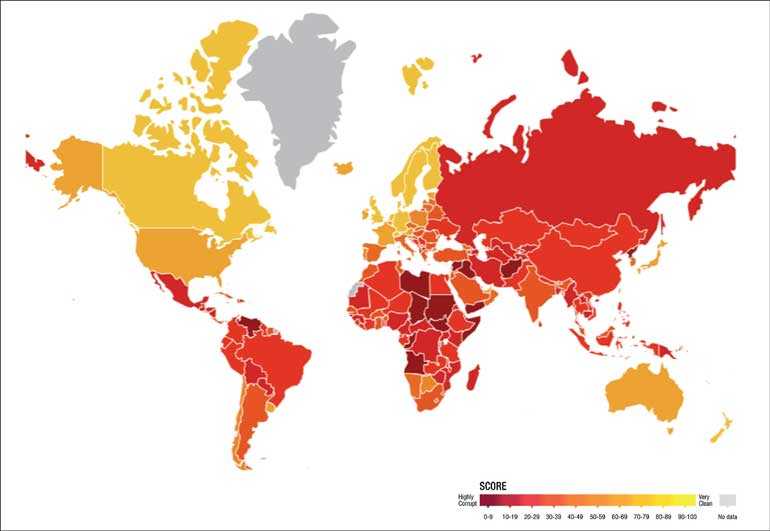

For now, it seems that those seeds – and Sri Lanka’s seeding in terms of how corrupt it is perceived to be – have fallen by the wayside. Though where once (2016) we were ranked 95th of 176, today we’re in 89th place with a score of 38 on an index where 0 is ‘highly corrupt’ and 100 is ‘very clean’. Last year, we had the same score (91st of 180 ranked countries). And our failure to improve our score despite a slightly higher ranking means that Sri Lanka may be as beautiful as Bali on Lonely Planet’s 2019 brochure. But we swim with the likes of Swaziland (90/180) on TI’s CPI 2018, where the average global country score is 43 and South Asia’s is 44. (In general, TI says most countries worldwide have failed to stem or stymie leave alone reverse the tide of corruption.)

While we’re nowhere near as bad as Somalia (score 10), Syria and South Sudan (both at 13), Sri Lanka is perceived as being the third most corrupt country in South Asia after Bhutan (25th of 100) and India (78/100). Sri Lanka averaged 83.53 from 2002 until 2018, reaching an all-time high of 97 in 2009 – the year our 26-year war ended and a record low of 52 in 2002… another year of political turmoil when CBK pulled the plug on the then UNP’s Govt. In more recent times, our country score has ranged from 32 in 2010 (rank 91 of 178) to 40 (2012). In the main, we bobbed about in the 37-38 score range in 2013-14-15.

All right-y then! So what does this all have to do with the price of eggs?

Bad eggs

One thing we must keep in mind is that the index is based on perceptions, which have a tenuous (if tenaciously researched) link to reality. TI tells us that CPI deals with “perceived levels of public sector corruption”, adding that “as such, the existence of a legislative framework – without the will or operational ability to ensure timely justice – reflects on Sri Lanka’s clear lack of progress to date.”

Its Sri Lankan chapter chief elaborates: “With the likely conclusion of several high-profile corruption cases in 2019, it is essential that all authorities uphold their impartiality and independence. If the application of the law is interpreted as selective or politically motivated, it could prove detrimental to the anti-corruption drive and the justice system.”

Still, what of the price of eggs in our island republic?

Basket case

An important conclusion to reach might be – as Transparency International itself has inferred – is there is a link between corruption and the health of nation-states. So-called ‘full democracies’ tend to score an average of 75 on the CPI, more towards to the ‘clean’ end of the perceptions spectrum. Those defined by TI as ‘flawed democracies’ rack up an average score of 49. And ‘hybrid regimes’ – a mix of democracy with elements of authoritarianism – score in the range of 35. (Autocratic regimes register average scores of 30 or so on the CPI.) So the think tank version of Sri Lanka’s CPI score plunks it between a flawed democracy and a hybrid regime. Tell us about it, TI!

If the CPI suggests that it’s time to make “real progress against corruption and strengthen democracy around the world”, TI’s call on all governments to strengthen vigorous checks and balances over political power, and ensure the ability of democratic institutions to operate without intimidation, is timely. In fact, the watchdog in tandem with civil society has been agitating for anticorruption legislation, practice and enforcement since our war of nearly three decades ended 10 years ago.

Fickle bureaucracy

We in the Fourth Estate must also nod to TI’s desire to support a free media milieu by ensuring the safety of journalists and their ability to work without intimidation of any ilk. The organization’s call to support civil society institutions, which facilitate critical political engagement and public oversight over government spending, particularly at the local level, is also salutary in terms of arresting alarming trends in how the state sector is perceived.

We endorse them, and can add a few more mirrors in which to reflect back at the Berlin-based ‘anticorruption coalition’ (as it styles itself) our own perception of state/national corruption. Be TI’s yardsticks for measuring corruption as they may – a rigorous methodology bolstered by meticulous research – we have our own gauges. It is far more fly-by-wire than any index. But perhaps far more perceptive and insightful! And rather than a rank or score, it is a finger – index or otherwise – that we use to show our corrupt bureaucrats and politicos what we think of them…

Failed statesmen

For as long as presidents declare egregious street-level warfare on drug pushers but pal up to traffickers in minister and mandarin ranks, perceptions of high-level national corruption will remain rife. And as long as prime ministers who promised to introduce and sustain a new political culture hobnob with goblins allegedly culpable of genocide and gremlins guilty of murder and grand larceny at public events, perceptions of corruption will dismay the sea-green incorruptible civil society champions who still mouth platitudes about Mr Clean. And the less said about how leftover cheats, thieves and robbers from previous regimes still seem to be at large, to pursue life, liberty and happiness, the better – it seems.

In fact, for as long as progressive legal reforms such as giving citizens the right to freely access asset declarations of public representatives (vide RTI) and the National Audit Bill fail to deliver – at least in terms of raising Sri Lanka’s anticorruption profile – we’ll be left holding the baby of a lack of bureaucratic probity and also think political will has been thrown out with the bathwater.

That is probably why TI’s Sri Lanka chief said last year after CPI 2017 was released: “It would seem that the anticorruption drive has limited momentum.” We wouldn’t be surprised if he repeated himself in 2019. And CPI 2018 – for all its rigour – is only the tip of the iceberg.

We know! think! suspect! that the rot runs rather deeper than that. It is time to dig, expose, uncover. The inauguration of a centre for investigative journalism in Sri Lanka in the same week as the CPI was released harbours some hope in this respect. Sure there’s miles to go but it seems some old hacks and serious journalists are not going to sleep soon… unless it’s with the fishes. So once more into the breach to close the wall and bridge that gap!

(Journalist | Editor-at-large of LMD | Writer #SpeakingTruthToPower)