Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Saturday, 23 December 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Aysha Maryam Cassim

As you pass the fruit stalls in Horagolla, Nittambuwa, a few kilometres away, along the Colombo-Kandy main road lies another street spectacle – the Kajugama in Bataleeya.

Boasting a long history of over 200 years, the cashew colony of Sri Lanka was established and revamped during late President Premadasa’s tenure. Roadside stalls were erected as a part of his vision to help the villagers in Kajugama whose livelihood depends solely on the sale of cashew to travellers, especially foreigners.

Cashew, the evergreen tropical tree has become a cash crop today. But it has never produced easy money for anyone.

It’s believed that cashew orchards first originated in Brazil. From the 16th century, Portuguese sailors moved South American plants around the world, introducing their native fruits and nuts to people in Malacca and East Africa.

Cashew cultivation entails a lot of risks. The shelling process is laborious and time-consuming.

Cashew season in Sri Lanka begins in March and continues through April. The vendors in Bataleeya get their nuts from Wariyapola, Wanathawillu, Wewagama, Giriulla, Kuliyapitiya, Puttalam, Ampara, Mahiyangana, Galgamuwa, Galewela and villages in the Eastern Province.

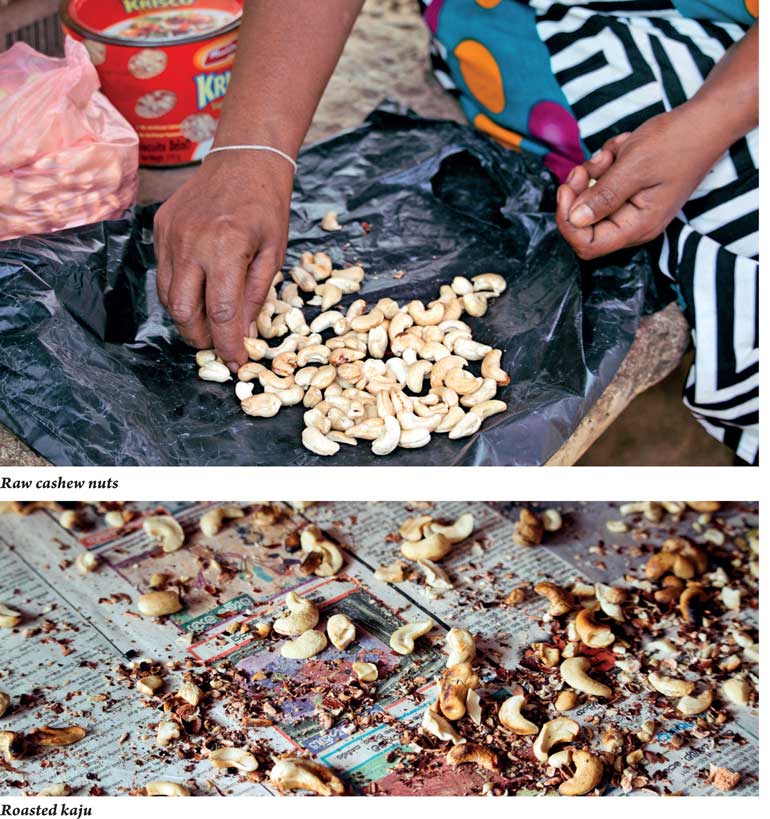

The nuts are consumed as edible snacks and being sold as expensive value-added products ranging from raw, roasted, spiced and fried kernels.

The global cashew economy is booming and Sri Lanka has to compete with some of the largest cashew exporters in the world including Africa, Brazil, Vietnam, and neighbouring India.

While the cashew economy has a positive macroeconomic impact on our local industry, the prosperous years are coming to an end due to many weaknesses. Even though Sri Lanka is endowed with fertile soils, abundant water and a climate favourable for cashew cultivation, over the last three years, production has dropped significantly.

The lack of investment and adequate financial mechanisms, labour intensive production methods, shortage of harvest are some of the reasons that caused the local cashew market to stagnate. The cashew cultivators are experiencing the hard times of their industry as much as the vendors in Kajugama.

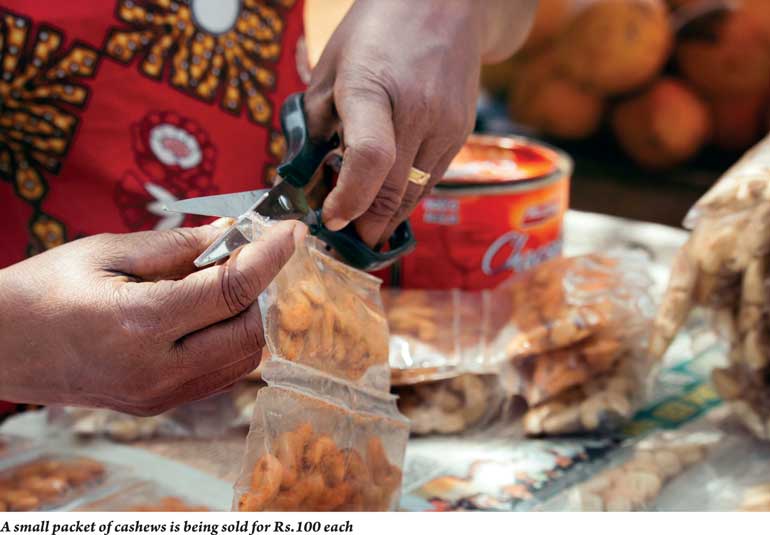

I spoke to few kaju sellers in Bataleeya – Kajugama. Today, you seldom see women clad in ‘reddai hattei’ (cloth and jacket) waving their hands to hail vehicles which pass by on the A9. Stores displaying a smorgasbord of cashew products have replaced the traditional makeshift huts sheltered with coconut leaves. A small packet, which consists of around 10-12 nuts inside, is being sold for Rs. 100 today.

Kaju curry, a delicacy in Sri Lankan cuisine, is best served as an accompaniment to your favourite rice and curry plate. Cashews are commonly used as an ingredient to garnish some of the local festive desserts like watalappam. Raw cashew nuts for cooking purposes can be bought for Rs. 2,500 per kilo whereas a 1kg packet of roasted nuts cost Rs. 3,500 in the market today.

The vendors purchase 1kg of leli kaju (nuts with the shell) for around Rs. 600. The profit margin is extremely low and price fluctuations throughout the year make their industry even more cumbersome.

The relatively reasonable prices of Indian cashew put the local cashew sellers and thousands of cultivators into a vulnerable state. According to a few locals, there is a distinct difference between the taste of the local and Kerala Kaju. Even the Indians seem to prefer the ‘kiri raha’ – the creamy taste – of Sri Lankan cashews over the Indian variety.

Mallika has been engaged in the cashew industry for the last 18 years sells thambili along with cashews in her small hut. She says villagers are losing their business because no one buys kaju as they used to now. She blames it on the high prices.

People have now opted to put up juice stalls and refreshment huts that sell pineapple and thambili which attract quite a lot of travellers.

Bataleeya Kajugama has lost its old charm now. Only a few locals stop at the cashew colony on their way to Colombo or Kandy. Occasionally, tourist coaches pullover near roadside huts. But their daily business depends on the guide’s preference as he directs his tourist to selected stalls.

There are customers who would stop by a hut and purchase a packet or two to support home-based industries. Kaju sellers do not want their children to follow in their footsteps or see them whiling away their days in the sun-dappled thatched huts, selling cashews.

The youth in Bataleeya, Kajugama don’t see a future in their cashew colony and move out of their village in search of education and better job opportunities.