Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Wednesday, 24 October 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Text and Pix by P.D. De Silva

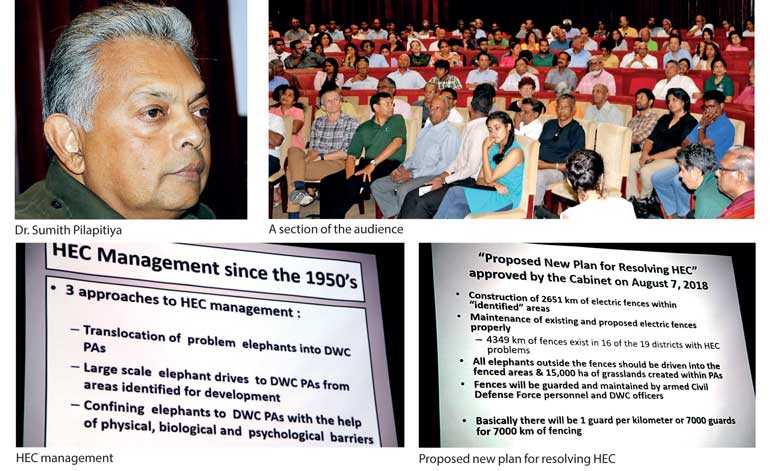

“In most instances, it’s not the elephants that kill humans; it’s the humans that get themselves killed by the elephants, due to their stupidity and negligence” said former Department of Wildlife Director General Dr. Sumith Pilapitiya, delivering the monthly lecture of the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society (WNPS), ‘Focus on human-elephant conflict management’ at the BMICH on 18 October. “70% of the human deaths by elephants are due to human irresponsibility,” he added.

He also said that the human deaths caused by elephants were a mere fraction when compared to the number of deaths due to motor accidents. Humans should take more responsibility for their lives; in most instances, it is people under the influence of alcohol that have got themselves killed, by challenging the elephants rather than avoiding them. Dr. Pilapitiya said that there were instances where people had been so negligent that they have crashed into elephants and got themselves killed. “If we are more responsible, and do not act stupidly, we can reduce the number of human deaths significantly,” he said.

In his opening remarks, Dr. Pilapitiya said that in the 1950s the Prime Minister of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, had said that he hoped someday Singapore will be like Ceylon, but from the mid1970s onwards every successive government in Sri Lanka has hoped that Sri Lanka would be like Singapore. “But we are far from it today. One of the main reasons is that we continue to keep making mistakes, and keep on repeating them without learning from them. When it comes to the management of the human-elephant conflict (HEC), once again I think we are in a similar situation,” he added.

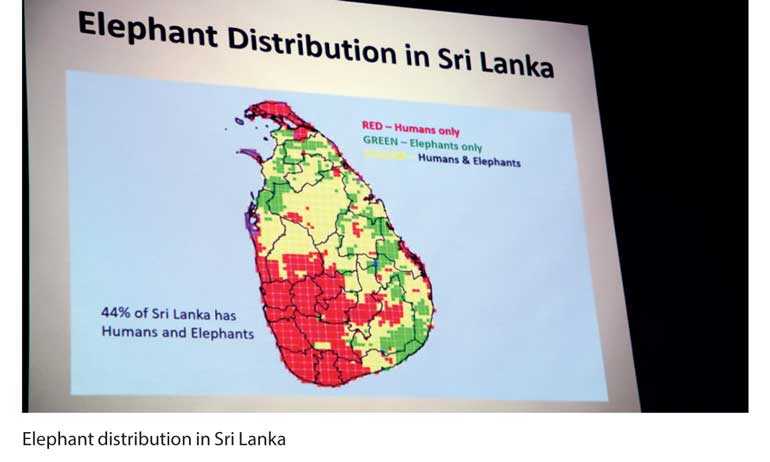

Referring to research material and statistics obtained from Dr Pruthuviraj Fernando and the Centre of Conservation and Research (CCR), Dr Pilapitiya said that in Sri Lanka, there are known to be about 6000 elephants in the wild. Sri Lanka has the highest density of Asian elephants, as well as a very high population density of humans, inasmuch as it has a declining natural resource base. “Unless we plan our development better, conflict is inevitable,” he warned. “HEC cannot be eliminated fully. As long as there are humans, and as long as there are elephants, there is going to be conflict. The only thing we could do is manage and minimise the conflict.t”

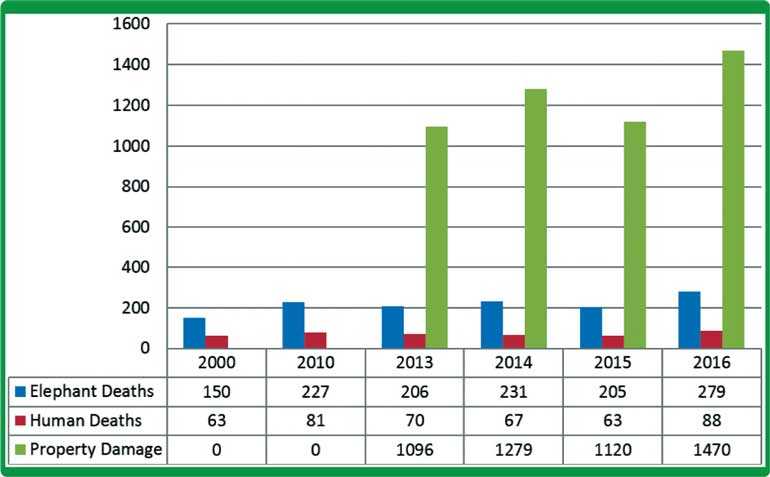

The HEC conflict started increasing with the large-scale irrigation and agricultural development drive commencing in the 1950s. In the year 2000, 150 elephants died, while only 63 humans were killed by elephants, but in 2017 256 elephants have died, while 87 humans have been killed by elephants.

The committee for the preservation of wildlife, appointed in 1959, came up with a plan to manage the HEC in the island, by driving all the elephants from developing areas to Department of Wildlife and Conservation (DWC)-protected areas through identified corridors, and fencing them in.

There were three approaches to manage the HEC, namely:

1. Translocation of problem elephants to DWC-protected areas

2. Large scale elephant drives from areas identified for development to DWC-protected areas

3. Confining elephants to DWC protected areas with the use of physical, biological and psychological barriers

If this strategy was successful, the HEC would have been minimal today. A survey done by the CCR shows that 44% of the land area of the island is being shared by humans and elephants. He said that research had shown that capture and translocation was not successful, nor could biological fences confine elephants within protected areas.

Dr Pilapitiya said that most national parks were at their maximum carrying capacity, and driving more elephants into such DWC-protected areas would result in the death of many elephants and calves due to starvation. He mentioned of one elephant drive that cost the Government Rs. 62 million to drive 225 elephants and calves into a DWC-protected area. He said that the end result was that the problem was not solved, as it was only the she-elephants and calves that were driven, while the single males and male groups had remained to forage on crops, and many of these elephants that were driven died due to starvation. “No one was held accountable for the fiasco and the waste of public funds. It was the development sector that should be held accountable, as the wildlife department was under severe pressure to carry out orders.”

The National Elephant Conservation Policy (NECP), which is in effect today, was drawn up by a multi-stakeholder committee, and approved by the Cabinet in 2006. Some of the goals of the policy are: to ensure the long-term survival of the elephant in the wild of Sri Lanka; to mitigate the human-elephant conflict; and to promote scientific research as the basis of conservation and management in the wild. The key point is managing as many viable populations of elephants as the land will support and the land holders will accept, both within and outside the system of protected areas. The policy also specifically states that when elephants lose their range, they die.

Dr Pilapitiya said that a new plan for resolving HEC was approved by the Cabinet of Ministers on 7 August, which is more in line with the 1959 plan and contradicts certain aspects of the 2006 policy. “To the best of my knowledge, policies should be driving plans, and plans should not be driving policies,” he stressed.

He also said that there are many positives in the recent Cabinet Paper, such as constructing 2651 km of electric fences within identified areas, which shows that there was still room to construct the fences on ecological boundaries, rather than the administrative boundaries. “It is imperative that the new fences are constructed on the ecological boundaries, and all existing fences should be relocated to ecological boundaries,” Dr Pilapitiya emphasised. Among his concerns was arming those who are to be entrusted with maintaining the fences with sophisticated weapons that are capable of killing an elephant in its tracks. “Accidents do happen!” he quipped.

Dr Pilapitiya said that development plans should be made accepting the elephants presence, and by working around them, rather than driving them away. “A win-win situation could be achieved by relocating the development project, rather than creating conflict.” He also said that it was scientific findings and past experience that should govern decision-making. “All options should be looked at. Community-based village fences and seasonal agricultural fences would be a viable alternative, if it is not possible to construct fences on the ecological boundaries,” he said.

“These were some things that I intended to do when I was the Director General of the Department of Wildlife and Conservation, but I resigned as I was unable to perform my duty due to political pressure,” Dr Pilapitiya admitted. “As conservationists, we can lobby and convince decision-makers to make the correct decisions, rather than repeat the mistakes we made in the past.”