The oil palm plantation industry is also facing turmoil with a temporary ban being enforced for the cultivation, based on emotional agitation by some groups with vested interests, sharply interrupting an entire development programme. Plants to the value of almost Rs. 400 m propagated with imported seeds with the necessary government approval is currently running the risk of being destroyed if they are not planted at the correct time.

Large-scale diversifications of innovative crops include arecanut, macadamia, pineapple, rambutan, soursop, lemon, oranges, papaya, avocado, passion fruit, pears, and vanilla together with spices like pepper, cloves, cardamom, and forestry initiatives from khaya, giant bamboo and other fuel-wood plantations.

Meanwhile, the 36 State-managed estates which were also managed by the same JEDB and SLSPC during the nationalised era remain a horrendous burden on taxpayers, being in arrears of close to Rs. 3 billion on their statutory dues of EPF, ETF and Gratuity and the Government continues to subsidise them to the tune of Rs. 1.5 billion a year. Here, the State has ample opportunity to turn its attention to the massive loss making State-managed plantations and implement so called ‘alternative models’.

(The writer is Chairman, Planters’ Association of Ceylon.)

Government and stakeholders must clearly understand that plantations cannot be managed in the historical manner given the current political, environmental and economic issues and continue to be viable business entities. Provisions for changes are available in the lease document and RPCs must be given a free hand to exercise the rights without interference and subsequent directives which interrupt the development programmes. Each RPC has a business plan based on indicators such as location of the plantations, crop mix, availability of workers and several factors which are not common across all plantations.

In the spirit of a privatised plantation sector

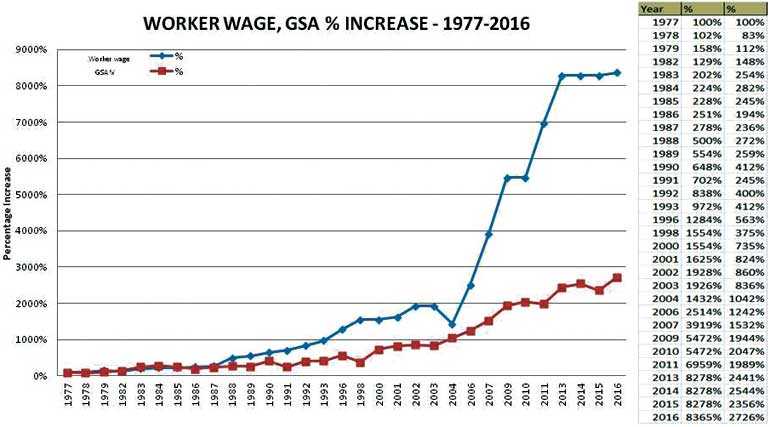

RPCs have invested a cumulative Rs. 70 billion between 1992 and 2016, contributing seven billion in lease rentals and a further 1.72 billion in income tax, coupled with dividends to Sri Lankan shareholders, totalling Rs. 8.17 billion, despite continuing challenges from diminishing availability of labour, incessant increases in labour wages not linked to productivity. The emergence of competitors like Kenya, operating on significantly larger economies of scale to produce volumes of tea, at drastically lower costs of production poses a big risk.

In addition to the clear superiority of RPC management in terms of productivity, it has only been under our stewardship that more uncompromising, environmental protection standards have been adopted. These include Rainforest Alliance certifications secured only upon the completion of a stringent process of auditing and the implementation of extensive environmental safeguards. To date most RPCs have secured the Green Frog seal of compliance propelling them to the prestigious Global Sustainable Agriculture Network standard.

Similar efforts have been channelled towards forest conservation and rehabilitation, with the majority of RPCs certified with the Forest Stewardship Council. Membership requires organisations to develop national forestry standards, localised to meet the unique requirements of each natural habitat, as per global standards.

To-date RPCs have cultivated in excess of 20,000 ha of forestry.

We wish to recognise and thank the Governmental authorities for commencement of guidelines towards a national policy for commercial forestry, on a request by the Planters’ Association. Despite a five-year forestry plan in place, a sudden ban, imposed five years ago on felling timber which is grown for fuel wood, meant that estates had to transport their requirement of fuel wood at an additional cost, causing additional and unnecessary burden on the bottom-line.

At present, there are 688 International certifications for 297 RPC factories including HACCP, ISO 22000, Fair Trade, Forest Stewardship Certification (FSC) ISO 9000, Care Quality Commission (CQC), Ethical Tea Partnership (ETP), UTZ, Rainforest Alliance (RA), Global GAP, SA etc., thereby ensuring the maintenance of extremely strict production and processing standards that ensure the safety of consumers, workers and the wider environment.

Furthermore, the ‘Ceylon Tea’ image and the branding of Food Factory Concept, Chemical Free Tea, Cleanest Tea in the world, Ethically Managed Plantations, Zero Child Employment, Ozone Friendly Tea, Sustainable Agriculture, Product Traceability to Source and Single Origin Estate Marks are predominantly RPC standards which is a huge plus for the image of Ceylon Tea and its branding.

Other internationally-accepted certifications which entail rigorous compliances with environmental, agricultural, economic and social standards of conduct, obtained by RPCs include Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) for Rubber and Cinnamon processing, Global Organic Latex Standard, for rubber ISO 9001:2008 Quality Management Systems Certification, for Oil Palm & Fruits, while the Round Table on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) certification is work in progress.

To-date not a single estate worker has been laid off; instead, their opportunities have increased with the productivity linked clause attached to their daily wage. Living conditions have improved vastly with two-bedroom houses with en-suite toilets built to replace the line rooms. A total of 50,000 such homes have been built in an ongoing effort for the 180,000 families that still live on RPC estates – all of whom may not be actually working in the fields.

From schools to hospitals, crèches to retirement homes, ongoing welfare activity to one-tenth of the country’s population is a priority of the RPCs which constitute the Plantations Human Development Trust (PHDT) along with trade unions and Government. Today an estate worker has the ability to earn in excess of Rs. 25,000 per month, in addition to all other infrastructure facilities provided by RPCs.

The true strengths of Sri Lanka’s plantation industry and their source

In light of these and many other achievements by the RPCs, standards of Sri Lanka’s plantations have been elevated far beyond its difficult past and therefore we assert that in truth, many of the strengths that remain in our industry today are initiatives taken by the RPCs. Environmental protection and quality standards have been implemented across the RPC sectors, where none were in place before privatisation. Our produce continues to fetch favourable – and often times record breaking prices from international buyers.

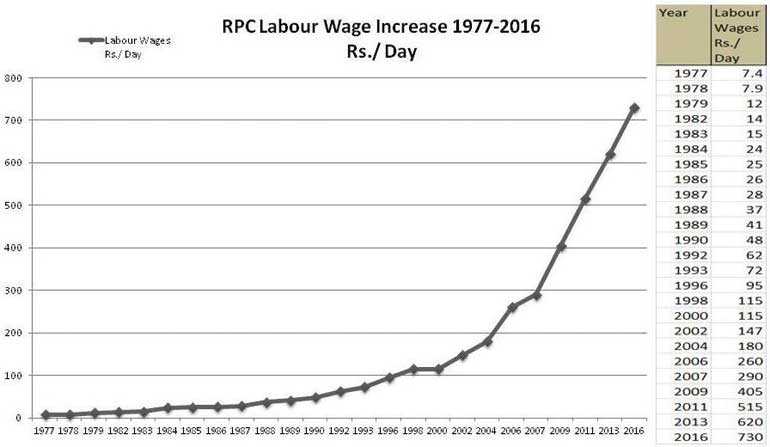

To say that worker wages have been increased periodically is an understatement. Wage increments have been awarded not commensurate with productivity, politically prodded and not considering the competitiveness of the company. Holding back wage increments was never the RPC agenda; however linking it to productivity will be the future of the plantation industry in Sri Lanka.

Despite constant politically motivated interference, many RPCs have commenced investments into crop diversification in order to consolidate revenue streams, even when various Governments have continued to vacillate on vital policies such as the importation of seed material. Meanwhile, important progress is being made to emulate the successful examples of RPCs who have partnered with large conglomerates to enter into value addition; something which did not exist during the time of State management.

Diversification through tea tourism is hugely successful. These include tea factory tours, hotels and niche luxury tea trails experiences –attracting high-spending tourists from across the globe – helping to further raise the profile of the island as a vibrant tourist destination. Many others are working on investments into this sector with the Planter’s Association committed to supporting the relentless exploration of innovative diversifications.

Favourable policies that will look at the industry 50 years from now and start sowing the seeds to propel it to a future-ready, economic power base, is the need of the hour. As an industry we cannot afford any more random ad-hoc policy decisions. Extending leases is an economic imperative, given crop cycles of rubber and oil palm. RPCs must be assured that leased land will not be annexed or encroached through political heavy handedness.

Ultimately, the RPCs each need to be allowed to draw upon their precious experience gained from the last quarter century of management, in a rapidly changing environment, to autonomously decide on the best course of action for each company, in alignment with a common ethic of sustainable, profitable, diversified plantations.

(The writer is Chairman, Planters’ Association of Ceylon.)

While coffee might seem to be the ‘go-to’ drink for those seeking a hot beverage, the world actually runs on tea. Aside from water, tea is the most popular beverage in the world and in the United States alone; tea imports have risen over 400% since 1990. It would be futile if we don’t capitalise on the trend and re-instate our position of being the number one exporter in USD terms.

While coffee might seem to be the ‘go-to’ drink for those seeking a hot beverage, the world actually runs on tea. Aside from water, tea is the most popular beverage in the world and in the United States alone; tea imports have risen over 400% since 1990. It would be futile if we don’t capitalise on the trend and re-instate our position of being the number one exporter in USD terms.