Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Thursday, 24 October 2019 00:27 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The Planters’ Association of Ceylon sounded a cautionary note with regard to the health and sustainability of the entire tea industry – including Regional Plantation Companies (RPC), and Government and smallholder sectors at large – as tea and rubber prices at the Colombo auction continuously plummeted in 2019.

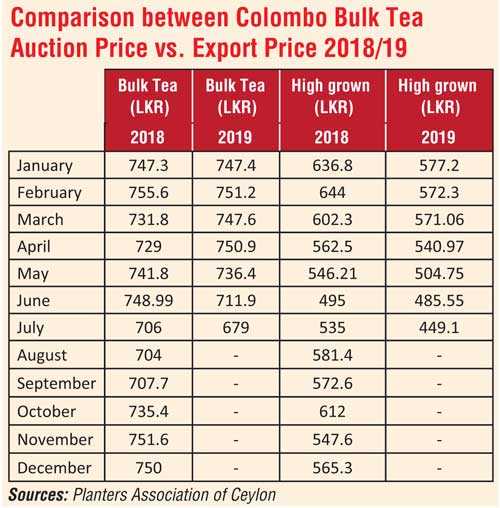

At the start of 2018, the high grown sales average – which is comprised mainly of RPC teas – stood at Rs. 636.8 per kilo, before dropping to an annual low of Rs. 495 per kilo and concluding the year at a price of Rs. 565.3 per kilo.

Similarly, the high grown average in 2019 peaked in January at Rs. 577.2 before plummeting over each successive month down to Rs. 449.1 per kilo by July while all indications point to a continuing weakening of prices across the high grown sales average.

By way of contrast however, the PA drew attention to a substantial and growing discrepancy in the trends of export price of bulk tea which had essentially been kept stable – if not improved - despite plummeting auction prices – an unprecedented development in the local industry.

In January 2018, bulk tea was exported at a rate of Rs. 747.3. Despite the massive reduction in prices at auction, bulk tea export prices one year later stood at Rs. 747.4, and reached a two-year low of Rs. 679 per kilo in July 2019.

According to the PA these sharp reductions in the price available to Sri Lankan tea producers at auction are also clear evidence of the entire tea industry’s urgent need to rapidly transition into a revenue share model for plantation sector workers, and away from the traditional wage models introduced during the time of colonisation and state control of the tea industry.

“It has become clear beyond a shadow of a doubt that the current wage model which remains totally uncoupled from productivity simply cannot stand – let alone current demands for a Rs. 1,000 daily wage irrespective of tea prices or productivity. Aside from the fact that Sri Lankan plantation workers are comfortably the best-paid in the global tea industry – our industry is increasingly unanimous in our demand for an immediate shift to a revenue share model as the only feasible path to long-term sustainability. These are serious challenges that threaten the stability of the entire industry. Low prices have already resulted in factory closures, and even smallholders are facing severe difficulties. Without a rational and supportive policy framework in place, such reforms will not be possible. The Government must intervene in consultation with all stakeholders on a priority basis,” the PA stated.

Commenting on the Sri Lanka Tea Board allowing imports of cheap South Indian teas to be value-added under the category of speciality teas for re-export, the PA further noted unscrupulous importers had already been caught sending these cheaper teas back to estate factories for bulk packaging, and called for much stricter controls and monitoring of importers for re-export.

“Particularly at a time when we are facing some of the worst prices on recent record, the move to allow importation of cheap South Indian Teas, and the lack of controls and enforcement by the Regulator to prevent individuals and firms from abusing this dispensation, is only adding fuel to the fire. What we need to be doing is supporting and encouraging local producers instead of facilitating others overseas to sell us their lowest quality tea to be blended with – or passed off as – Ceylon Tea.

The margin between tea auction and export prices has always been a constant, largely owing to the value addition and logistics management necessary between the auction and export.

“The PA reiterates the vital importance of all stakeholders carrying out their business operations in a manner which ensures the sustainability and continuing commercial viability of Ceylon Tea as a whole. As producers, our members are already facing massive challenges on all fronts. The wages we pay to harvesters and tappers are among the highest in the world, yet we struggle to maintain productivity owing to a combination of factors. This means that our total cost of production is also the highest in the world – of which labour wages account for almost 70% of total costs.

“All operations, development and maintenance of RPC tea and rubber estates are funded by revenue generated by each RPC. Given the high cost of production and prolonged low prices, the entire industry – including but not limited to RPCs – will be compelled to cut back spending except for the most essential operational expenses, eventually leading to a drop in volume and quality of yield,” the PA stated.

Tea producers under pressure from all sides

In that regard, the PA strongly cautioned all stakeholders against entering into a short-sighted ‘race to the bottom’ in relation to tea prices. “As producers, we are well aware of the fact that when it comes to bulk tea exports – it is the international buyer who wields the most bargaining power today, especially with the rise of global competitors. If such a negative cycle is allowed to continue indefinitely, it will spell doom for tea producers, and without them, all other components in the value chain will also go out of business.”

Over the past year, bulk tea exports have been able to maintain and even improve prices Year-on-Year while our best high grown teas receive continuously weaker prices at auction. These dynamics were once again brought to the fore at the recently concluded PA Annual General Meeting when PA Chairman, Sunil Poholiyadde called for State intervention to set and guarantee minimum prices at the tea auctions in order to cushion the entire sector against protracted periods of low prices.

After tea is initially processed and packed in bulk for sale at auction, it is the responsibility of the producers to transfer the tea to the broker and exporter warehouses following which value addition takes place for export to international markets. Notably, leading Tea Brokers too have acknowledged the clear and significant discrepancy which emerged over the past year.

High-grown teas are just one component in bulk tea exports that are often blended with medium and low grown teas in order to create flavours suited to the palettes of specific markets – particularly those in the Middle-East. While these and other perennial challenges have helped to keep prices low, these dynamics alone are insufficient to explain the widening gap between auction and export prices.

In that context, the PA also drew attention to the importation of teas permitted under the speciality tea category, noting that some firms had sought and received permission from the Sri Lanka Tea Board to import cheap South Indian teas of lesser value than what is produced domestically in Sri Lanka. Typically the classification of ‘speciality teas’ are exotic varietals which cannot be grown in Sri Lanka such as Darjeeling, Malawai, and East African CTCs, by contrast with low-quality teas currently imported from South Indian estates which are currently being brought into the country and disingenuously labelled as ‘Packed in Ceylon’

Immediate action needed to revive auction prices

Moving forward, the PA highlighted several areas in which stakeholder action could be mobilised to help revive Colombo tea auction prices including the development of mechanisms to secure payments from exports to major tea importing nations like Iran and Russia which are currently under sanction.

Meanwhile, RPCs and tea producers around the country would have to continue to maintain a rigorous focus on quality throughout the value chain in order to preserve the strong brand equity of Pure Ceylon Tea.

Crucially however, the PA advocated for immediate steps to be taken to protect the local industry through the imposition of a minimum value of at least $ 3 per kilo on speciality teas in order to prevent $ 1.5 South Indian teas from being included in the same category. In this manner, local producers would be provided with even a small measure of immediate protection which would support efforts to maintain and enhance quality in the local production process.