Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Friday, 14 July 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Anvar Alikhan

I remember once writing an ad for Ceylon tea for an international audience. The image showed a shattered tea cup, and the line said: ‘Sorry, but your tea cup is probably not good enough for this tea’. The ad then went on to talk about how to appreciate a good Ceylon tea – starting with getting yourself a delicate China tea cup to drink it from, because a regular pottery cup ruins the experience. Talking with tea-tasters to collect the information for that ad was my first introduction to the world of tea appreciation, and its rituals. And that set me on a journey of learning that still continues. Which is why reading ‘Ceylon Tea: The Trade That Made a Nation’ was a special pleasure for me.

I am fascinated by the idea that ‘Geography is History’. I suppose that concept holds true for most countries in some way, but it perhaps holds particularly true for Sri Lanka. And what Richard Simon does, essentially, is to explore this theme. He begins with Marco Polo, who apparently said of Sri Lanka, ‘For its actual size, it is better circumstanced than any other island in the world’. And from there he brings us down through the centuries – from the time Sri Lanka was the ‘Spice Isle’ of the Dutch, supplying cinnamon to titillate the palates of 17th century Europe, through the glory days when it became the world’s largest supplier of coffee, to the ‘Great Coffee Disaster’ of the 1870s. And then, from the felicitous replacement of coffee with tea, through the various upheavals of the 20th century – economic, political, ethnic and military – he brings us to the present day.

Along the way, Simon touches upon fascinating subjects, like how Rajasinha II, the 17th century king of Kandy, regretted having supported the Dutch against the Portuguese, bitterly remarking that he had merely ‘traded ginger for cinnamon’; how a Scotsman named James Taylor transformed Sri Lanka’s future with a little experiment at a place named Loolecondera; how Sir Thomas Lipton created the global market for tea, by making it more affordable; and why, unlike in the case of wine, there is no ‘Grand Cru’ of tea. But even more interesting, perhaps, are some of the what-ifs of history that Simon suggests, like: what if the British had not mistaken the ancient Sinhalese custom of ‘rajakariya’ for laziness, and used local labourers instead of importing Tamil labourers? And what if, instead of cultivating tea, they had decided to cultivate some obscure crop like cinchona, or indigo (as it may well have done)? Thought-provoking questions, indeed!

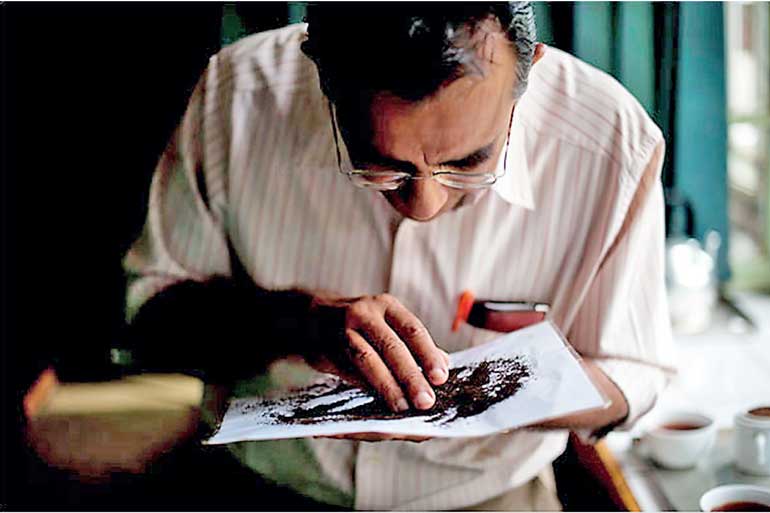

Ceylon Tea is, indeed a story of geography inextricably intertwined with history, and Simon tells it with vivacity, elegance and delightful turn of phrase. He notes, for example, that the nineteenth-century planter made up for his dietary deficiencies ‘by frequent recourse to spirituous consolation’. Of the incompetent Governor Torrington, he writes that he ordered his army to suppress rebels, ‘which they did with sanguinary enthusiasm’. Of planting in the mid 19th century, he says it was it was a career for ‘poor lads with broad shoulders and narrow prospects’. And he describes the tea taster as ‘the practitioner of a dark art whose lore was for long decades a closely guarded secret amongst the brotherhood of tea’.

Ceylon Tea is a splendidly produced book, thanks to Dominic Sansoni’s sumptuous photography and the charming archival images that accompany the narrative (having worked on similar books myself, I am filled with admiration for the painstaking pictorial research that has evidently gone into this). In fact, the book is perhaps a little too good-looking for its own good: the danger is that people might treat it as just a ‘coffee-table book’, simply admiring the images, and keeping it as a living room adornment – thereby missing out on the richly detailed and pleasurable narrative.

In a sense, reading ‘Ceylon Tea’ reminded me of ‘The Panama Hat Trail’ by Tom Miller, about the Panama hat industry in Ecuador –one of my favourite business books, because of the way it describes the workings of the industry in great detail, and yet does so in the engaging manner of a best-selling travel book (I can’t think of anything duller than the inner mechanism of Sri Lanka’s tea auctions, for example, and yet Simon presents it in an entirely readable – almost entertaining – manner). In another sense, Ceylon Tea reminded me of L’Aventure du Sucre, that wonderful museum in Mauritius, set in an abandoned nineteenth-century sugar mill, which presents the history of Mauritius and its people – the colonial eras of the Dutch, French and British; the slave trade; the hypocrisies of the indentured labour system – all through the history of the sugar industry, upon which the island’s economy was built. The parallels with Sri Lanka and its tea industry are striking.

(The writer is Strategy Consultant, J.Walter Thompson, India. He spent some of the best years of his life working in Colombo. He can be reached at [email protected],