Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Thursday, 12 April 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Another year’s growth data has been released and some of us may be red-faced!

Another year’s growth data has been released and some of us may be red-faced!

The economy grew by 3.1% in real terms, which has been the lowest for 16 years. Sri Lanka was ranked 71st among 138 nations in the 2016/17 ranking of the Global Competitive Index and 90th among 127 economic entities in the 2016 Global Innovation Index ranking.

These are not healthy positions and as some unofficially express, if one is below the 25th position, you may skip additional details. None of these rankings and the underlying set of data are encouraging and should be inputs for decision making by the planners.

Sri Lanka today, though identified as a middle-income country, has a structurally poor, non-competitive industry sector. Over the years this sector mostly has lacked the vision and the direction required to be a competitive contributing sector to the economy.

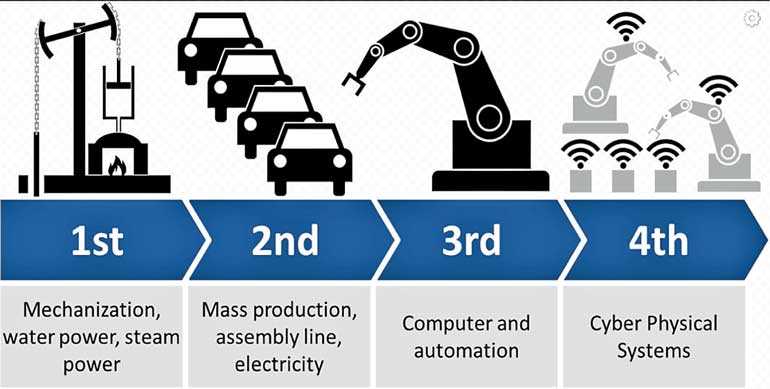

The world is marching towards Industry 4.0 (cyber physical systems) whilst the Sri Lankan economy is still seeing remittances from Middle East labour as the most important and the planners consistently claim Sri Lanka to be an agricultural country and direct policy with that underlying basis. Thus Sri Lanka has never aspired to be strong in manufacturing or in processing.

Industry 4.0, the new technology revolution, is considered to be revolutionary and with the ability to fundamentally change humankind. Eng. Wimalasurendra who is a pioneer pushed for industries once electricity was realised and he specifically identified salt-based industries and this was in 1932.

Today our electricity production is mostly to satisfy home consumers and that too at night-time. The night-time peak is effectively killing the CEB. It is time manufacturing is given its due place for an economic upswing.

An observation made by World Bank in 1952 is that ‘the rate of development in Ceylon is actually limited less by finance than by lack of technology at all levels’. Today we may have finance problems as well as technology problems. Sri Lanka has witnessed different stages of industrialisation efforts. In the period of 1920 to 1977 the country witnessed policy applications in varying ways to support import substitution. The post-1977 era suddenly witnessed markets opening up and export-driven manufacturing strategy adopted.

Sri Lanka’s journey to Middle Income Level status had been via services and with remittances added to good measure. As Central Bank in its Annual Report for 2016 pointed out, Sri Lanka has leapfrogged from an agrarian society to a service-based economy.

What is usual to observe is that developed nations usually have achieved such status through industrialisation. Another feature is that the contribution from manufacturing has weakened too with substantial contribution coming from the non-manufacturing industrial sectors.

Consequent to manufacturing becoming weaker it is not surprising to observe the steady falling of exports relative to GDP. The proportion of the value from high technology manufactured exports compared to all of the manufactured exports is amounting to only about 0.9%, which is an extremely low figure. Since independence in almost all the years it has been the norm for export income to be less than the expenditure on imports. The direct interpretation is that what the Sri Lankan economy has to offer in terms of exports is much less exciting. Similarly the interest internally is also on external goods and this unbridled consumerism has meant that the import expenditure is significant and thereby resulting in an even more difficult situation.

Sri Lanka can identify the industry development from the 1920s. An exception from the textile industry is the birth of Wellawatte Spinning & Weaving Mills in 1888, which had a chequered history till 1981 when it was closed down. It has been stated that post 1977 when it failed to meet with competition it had the largest collection of textile machinery of ‘antique value’.

The plantation industry sector had its beginning during the colonial times from around 1830 starting with coffee, when Ceylon became the birthplace for the desiccated coconut industry. The reason for the industry to start was simply due to the colonial interest in taking coconut products abroad but without incurring costs on transporting associated moisture. The tea industry today has a history of 150 years but in many situations if you visit a factory it is like walking into a museum.

Around the 1920s there was the view that the island should strive to be less dependent on the plantation industry. Report of the Industries Commission in 1922 identified a number of new industries glass, paper, soap, cement, Cyanamid, charcoal, acetic acid, alcohol and other chemical products, fish oil, fish manure and tinned fish as suitable to be set up in Ceylon.

The Government did launch pilot industrial projects from 1930 to entice the private sector to be engaged in manufacturing. However, these never yielded any results due to poor technology adoptability, lack of capital for investment and with a private sector which lacked experience as well as interest.

Sri Lanka in the 1950s had a better economy and a foreign exchange reserves due to war years and a bumper income from tea benefitting the nation. However, the gains have been frittered away with the Government engaged in welfare expenditure and without much of an effort in bringing structural reforms to the economy.

This lack of foresight and the complacency meant Sri Lanka slipping in the economic ladder since 1960s. Sri Lanka too may have had an entrepreneurial class that did engage in primary product processing but they never elevated themselves with additional influx of technology and investment to the next level. Innovative behaviour has not being evident at all.

The early 1960s witnessed some development in the industrial activities of the country, with restrictions imposed on the import of manufactured articles, which actually was due to acute foreign exchange crisis facing the country. The renewed policy interest in industrialisation with the State taking charge was subsequent to the report of Director of Industries (1957) and the 10-year plan (1959-68). However, political developments along with the deteriorating current account balance prevented much of the execution of these plans.

In the 1970s the Government again set up a committee with an emphasis on heavy chemicals to identify and prepare feasibility studies on manufacturing industries. It recommended an expanded caustic soda industry, ilmenite TiO2 industry, calcium carbide and associated industries (acetic acid, formalin and PVC), charcoal and other forms of carbon, sulphuric acid, soda ash, lime, alcohol and yeast industries.

There was never a major drive for the development of process industry in Sri Lanka. Even though the country is surrounded by the sea, Sri Lanka continue to import salt and fish. Perhaps it was through the misunderstanding that job creation was the major intention and chemical process industry usually is not a major job provider.

The chemical industry can thrive only in an industrial climate and integrative planning is important. With decision-makers consistently identifying Sri Lanka to be an agriculture-based country, this conducive climate never materialised.

Naylor who visited Ceylon in 1966 raised many questions with regard to all industries that were managed by State industrial corporations. An extract on paper is indicative of many of the pitfalls in decision-making that plagued all most all the industrial enterprises.

Paper – How did they err in choosing the wrong raw material? As a result, the plant is now uneconomically sited. Why couldn’t irrigation authorities and the Police protect the corporation’s water supply? How come irrigation authorities permit the tank to be exhausted without reserving an adequate quantity for the paper plant? How come irrigation authorities fail to repair the anicut? Why does Paper Corporation have to lose money to subsidise Government departments through sales at prices below the cost of production?

His report was an indictment of the way the industries have been managed from conception to operations and indicate the problems faced by the industry sector. Most of the industries were outright grants and only with the mindset of a trained workforce to run the system given there was no clear industrial work ethos that was developing. Some industries were clearly not planned with sustainability in mind and consequently became liabilities not because the objective was unsound but the adopted scale of operations.

Post-1977 era witnessed the establishment of Export Processing Zones and inducing Foreign Direct Investments (FDI). The opening up of the Katunayake EPZ in 1978 was quite an important event. Yet one cannot forget that Sri Lanka had the first industrial estate in this region going back to fifties when the Ekala Ja-Ela industrial estate was opened up for operations.

In 1989 the Government adopted an industry strategy, placing specific emphasis on export-led growth with the private sector taking a lead role. However, to date Sri Lanka cannot defend the comment that it still predominantly is a nation that ‘exports rubber and imports erasers’ in almost all its trade segments.

When perusing history of industry in Sri Lanka in modern times it is clearly seen that the change of political regimes with different political ideologies had meant industrial policies taking a serious beating. Industrial development needs foresight but short-termism has reigned.

Sri Lankan policymakers can be reminded of the advertisement once placed in ‘The Times’ by the Engineering Council of UK when British Government was moving with a very much service sector-based development mindset – No nation can have a well-fed, well-clothed healthy population with a service and a tourist-based economy! This was the essence of the full page advertisement that the Engineering Council ran as an open message to the Government. Sri Lanka needs to understand the same.

There is a critical need for revitalisation of the manufacturing sector. Coming in line with nations that have realised development status, this is the most likely path available to Sri Lanka in obtaining sustainable economic growth. Modernisation of industry and especially the manufacturing sector can have definite beneficial impacts on the other two sectors as well. Agriculture should be coupled to the industry sector in this modernisation.