Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Saturday, 19 September 2015 00:45 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By D.C. Ranatunga

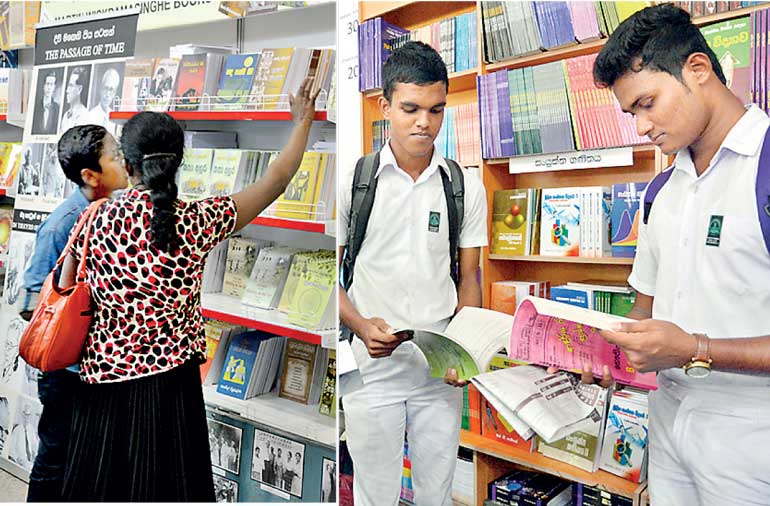

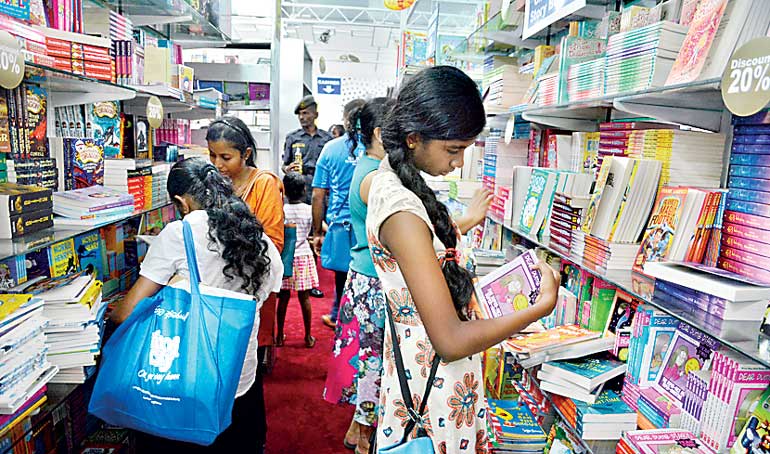

A few years back a friend told me that he sets aside five rupees every day and picks up the lot at the end of one year. Being a ‘bookworm,’ he takes the money and goes to the Book Fair – not once but several times. At the end of the Fair Week, he has collected a couple of bundles. His wife’s response every year is “Where are you going to keep these?” He somehow finds space. “The garage is also virtually full,” he confesses. Yet he keeps on buying more!

Come Book Fair time, there are many who cannot resist the temptation. They sometimes pick the same books they had bought earlier. But they are happy.

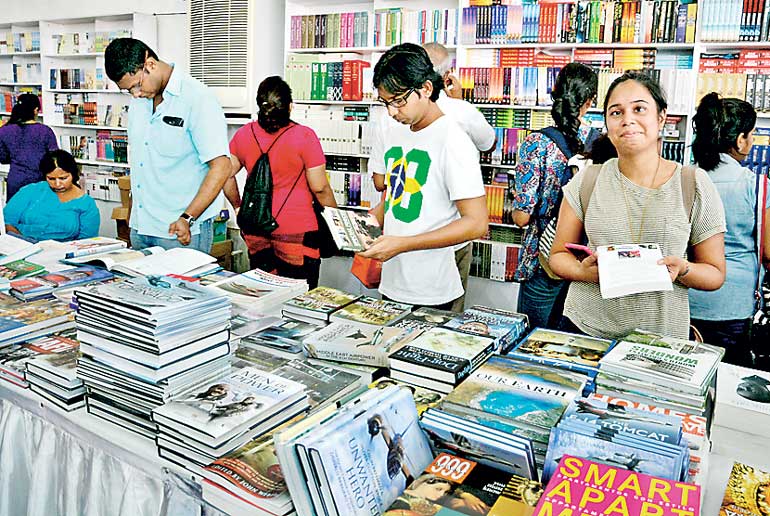

This year’s Colombo International Book Fair (CIBF) has just opened and goes on till Sunday, 27 September, covering two weekends. It is not only Sri Lanka’s largest-attended book fair, but is also a premier fair in South Asia. All the leading book publishers take part along with hundreds of others who are virtually unknown. The fair is popular with Indian publishers who make it a point to participate every year.

The fair is so successful obviously because the young and old alike still like to read books. Just as much as newspapers are still being bought in spite of TV, so is the reading of books.

It’s amazing how Sinhala books are coming out in numbers on varied topics. Every time you walk into a bookstore there are ‘new arrivals’ in numbers. I haven’t checked on Tamil publications but possibly the trend is the same.

True, the printing industry has come a long way with improvements in machinery, types of letters, layouts and designs making books more and more attractive. The Sinhala publications are keeping pace alright.

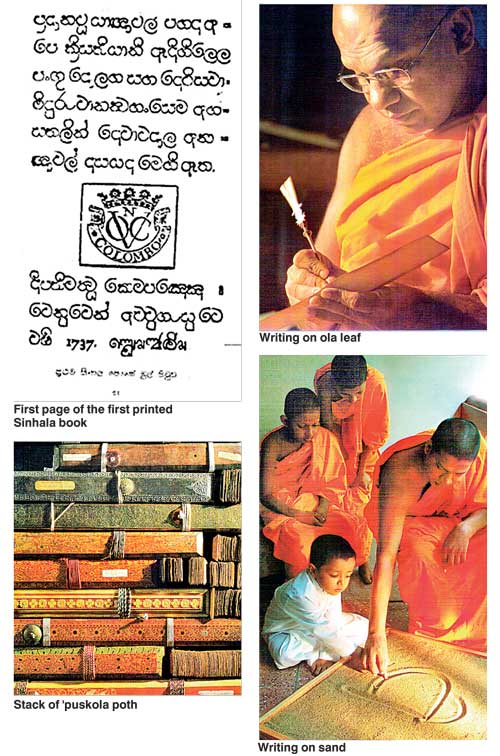

What a long journey it has been since the days we wrote the first letters on ‘veli’ (sand)! I remember the days I started schooling at the Sinhala school joining the ‘hodiya’ (kindergarten). We wrote on the ‘gallella’ (slate) using the ‘gal koora’ and read the ‘hodi potha’. As we grew up and sat on a long bench with at least four others with an equally long desk in front, we started writing with ink using nib pens (we had to use only a ‘g nib,’ which we were told, was the best to get the right curves of the letters) dipping the pen in white inkstands.

The desks had round spaces cut to shape for the inkstand to go in so that the ink was not spilt. They were constantly refilled from big ink bottles. This continued when we ‘graduated’ to sit on a desk and chair for oneself. At university level we used fountain pens when the pens were filled with ink and then came the ballpoint era.

Looking back it was a fascinating experience when today even the ballpoint pen is kept aside “for an emergency” and most of us use the laptop. As the President recently said in his opening address to Parliament, technology is moving so fast that “we should aim at getting the students to use iPads by the year 2020”.

Our great writer Martin Wickramasinghe vividly describes the days he learnt to write on sand. That was in the 1890s. In ‘Ape Game’ – ‘Lay Bare the Roots,’ he wrote: “I feel an eager curiosity to look back into the past stirring in me when I recall how I used to write, my forefinger pressing my middle finger on the sand board… a board painted black and its surface covered with a thick layer of sea sand. As the finger traced the Sinhalese letters upon it, the smooth sand parted, exposing the black board as curving black lines of letters. To a man who looked at them from a distance, they appeared like letters written in charcoal on a white board.”

Writing on ola leaves

Buddhist texts were documented in ‘puskola’ – ola or talipot leaves. The practice of writing on ola leaves continues to this day although it’s not widely practised. Until recent times horoscopes were written on ola leaves mainly to be preserved for several generations. They were rolled up and kept.

The material for preparing the writing leaf is taken from young unopened tender leaves from young trees. When the tender leaf is about to open, it is cut and taken off and slit open. Then the leaflets within are separated and taken out one by one. The midribs are removed and the strips of leaf blades in rolls are immersed in a pot filled with cold water. The vessel is placed over a slow fire till the water is gradually raised to boiling point. The heat is then reduced and the leaves are allowed to simmer in water for three or four hours. The leaves are later taken out and dried for a few days in the sun. This is followed by the exposure of the leaf in the open air to the dew for three nights for the leaf to be supple.

These leaves are rolled and kept until they are put through a process of smoothing and finishing. For this, each leaf is taken out and a weight is attached to one of the ends. It is then pulled up and down against the smooth surface of a horizontal cylinder of wood. Normally the trunk of an areca palm is used tied to two posts at a convenient height.

The leaf blades are cut into lengths ranging from nine to 32 inches and formed into book leaves. The width of each is two to three inches. Using a steel punch two holes are punched and filed together by passing pegs through each of the holes and through wooden boards on either side.

The writing on a palm leaf is done with an ‘ulkatuva’ – a stylus having a steel point. It is sharpened from time to time on an oiled stone. The lines forming letters are incised on the surface of the leaf. The stylus is made of metal such as gold, silver, copper or brass. Some are plain while some are ornamented.

Once a book is completed the leaves and the covers are strung together with a cord which passes through the punch holes on the left side of the leaves and the boards. A ‘puskola potha’ is thus born.

Invariably the Buddhist texts written on ola leaves are preserved in temples. The ‘pirith potha’ is one such text which is brought out whenever there is an all-night chanting of the stanzas.

Printing – the beginnings

Although the European powers came and occupied the maritime areas in the country from the beginning of the 16th century, it was not until the latter part of the 18th century that the printing of books in Sinhala was started. It was the Dutch missionaries who pursued the idea of printing books in Sinhala solely for the propagation of Christianity.

Setting up of vernacular schools was found to be a convenient way to converting the younger generation. Around 1725 they approached the Dutch Governor who initiated the preliminary work for Sinhala printing. The first step was casting the Sinhala types and moulding the required parts.

When Governor Peilat left, he left instructions to his successor to follow up “the establishment of a Sinhala Printing Office, so that the New Testament may be printed in that language”. However, the new governor did not show any interest and the project did not make any headway. He, in fact, ill-treated the Superintendent of the Arsenal, Gabriel Schade who was given the task of planning the preliminary work. So it was not until 1737 he was able complete the task with the support of a new governor and with the help of the Government in Java.

Referring to Gabriel Schade, one-time Government Archivist J.H.D. Paulusz states: “Vuyst’s ill-treatment had left a mark on him. He was feeble and broken in body, though still stout of heart. With the help of two clergymen, J.W. Konyn and J.P. Werzellius, who trained the required typesetters and mechanics in reading and arranging the Sinhala characters, he brought his work to the final stages. But his death about the middle of 1737 robbed him of the satisfaction of seeing this first Sinhalese book issued from the press a few months later...”

It is recorded that a Christian Prayer Book was the first Sinhala book to be printed in 1737 with movable Sinhala types invented by Gabriel Schade under the patronage and assistance of Governor Gustafi Willem Baron Van Imhoff.

The Buddhist revivalist movement coupled with the rise of nationalism by the middle of the 19th century during the British rule created the need to keep the public educated. The public debates between eloquent Buddhist monks and Christian missionaries had a huge impact.

In 1860, two printing machines were got down from Siam (Thailand) to print and distribute reading material among the Buddhists. These were set up in Galle – one at Dangedera and the other inside the Fort. The early Sinhala newspapers – ‘Lankalokaya’ and ‘Lakmini Pahana’ – had been printed at these presses. They were later given over to the Ranwella temple at Kataluwa in Ahangama and a few years back were caught up in a fire at the temple.

As the years passed, the printing industry in Sri Lanka progressed rapidly with the increasing demand for Sinhala and Tamil books. As technology advanced, printing has become streamlined. Typesetting and printing processes are so quick and easy today.

In the process, even for the reader of Sinhala and Tamil books, the era of e-books has dawned.