Tuesday Feb 10, 2026

Tuesday Feb 10, 2026

Saturday, 20 August 2016 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By D.C. Ranatunga

It was the first day of the Randoli Perahera in Kandy. In keeping with the age-old custom, Veddah Chief Uruvarige Vanniyale clad in a checked white sarong and bare-bodied, with the axe over his right shoulder and a container of bees’ honey on the other, visited the Dalada Maligawa. Accompanied by around 80 villagers from Dambana, he handed over the bees’ honey to the Diyawadana Nilame to be offered to the Sacred Tooth Relic.

Then he paid courtesy calls on the Mahanayaka Theras of Malwatta and Asgiriya Chapters and alerted them of the challenges faced by his fellowmen living in 62 villages in six districts. He stressed that it is with much effort that they continue to observe traditional customs and traditions.

Even collecting bees honey for the annual ‘pooja’ faces problems. According to him sometimes the law is against them in following these. They have had to change their lifestyles with development projects making inroads into their territories. There have been instances when they had refused to move out of their abodes.

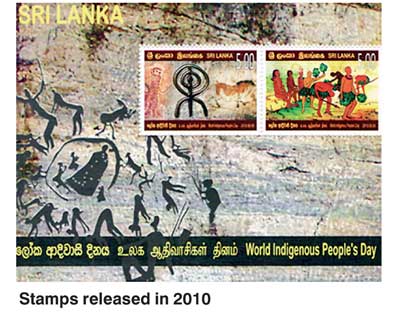

The previous week Uruvarige Vanniyale met with Government officials to discuss common issues. That was on the day commemorating the International Day of World’s Indigenous Day. August 9 is set apart to promote and protect the rights of the world’s indigenous population. The day is being observed since 1995 when the General Assembly of the United Nations declared the International Decade of the Indigenous People.

The United Nations had been concerned about the rights of the indigenous people and appointed the UN Working Group on the Indigenous Populations on the Submission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights. Its first meeting was held on 9 August 1982.

The theme of this year’s Indigenous Day was devoted to the right to education. Article 14 of the on the Rights of Indigenous People states that “indigenous peoples have the right to establish and control the educational systems and institutions providing education in their own languages, in a manner appropriate to the cultures of teaching and learning.”

Over the years in Sri Lanka young ones of ‘Vanniyalaththo’ – that’s how these ‘aasi vaadeen’ (indigenous people) like to be called – had no problem in attending the same schools as the other children. They have been enjoying the benefits of free education. I remember going for the launch of a book written by the first Veddah university graduate a few years back. T.M. Gunawardena graduated from the Colombo University offering Arts subject and started teaching at the Dambana Government school.

Now a fast-diminishing community, a member of this tribe is generally identified as a bare-chested man, carrying a short ‘porava’ – an axe and a bow and arrow on his shoulder with the hair tied behind in a ‘konde’. In the early days both the male and the female wore only a short loin cloth round the waist. Things have gradually changed over the years. They wear very much as the others do but the elders prefer to maintain the traditional look.

Origins

There are several theories about the origins of the indigenous people of Sri Lanka, the ‘Vanniyalaaththo’ – dwellers of the forest. Whenever the beginnings were, all evidence is to the fact that they were primitive people who lived by hunting in the forests. The origin of the term ‘Veddah’ is derived from the Sanskrit word ‘vyadha’ meaning the hunter with a bow and arrow.

According to some, they descend from a direct line from as far back as 16,000 BC while other researchers believe they have come down since 12,500 BC when there were settlements and civilisations within Sri Lanka.

According to the Mahavamsa, however, their lineage is directly connected to Vijaya, the first king of Sri Lanka, dating back to 5th/6th centuries BC. When Vijaya abandoned Kuveni, whom he met as soon he arrived in the shores of Sri Lanka from India, for a Pandyan princess, his two children by Kuveni had left for the valleys of the Ratnapura District where gradually the population grew leading to the present Veddah community. Among the anthropologists supporting this theory is British anthropologist C.G. Seligman (1873-1940) who had done a detailed study of the Veddahs.

Anthropologist Dr. Nandadeva Wijesekera says that the word Sabaragamuwa, the province where Ratnapura is located, has derived from the dwelling of the Veddahs – ‘Sabaras’ – interpreted as ‘forest dwellers’. The existence of several villages in the Sabagamuwa District like ‘Vedhi Gala’, ‘Veddah Ala’ and ‘Vedhi Kanda’ strengthens this thepry.

Balangoda Man

Former Director-General of Archaeology, Dr. S.V. Deraniyagala points out that the Veddahs can find a common ancestor in the ‘Balangoda Man’ going back to even further than the time periods mentioned above.

He describes the Balangoda Man: “These anatomically modern prehistoric humans in Sri Lanka are referred to as Balangoda Man in popular parlance (derived from his being responsible for the Mesolithic ‘Balangoda Culture’ first defined near sites in Balangoda). He stood at an estimated height of 174cm for males and 166 m for females in certain samples, which is considerably higher when compared with genetics of the present-day population in Sri Lanka. The bones are robust, with thick skull-bones, prominent brow-ridges, depressed wide noses, heavy jaws and short necks. The teeth are conspicuously large. These traits have survived in varying degrees among the Veddahs and certain Sinhalese groups, thus pointing to Balangoda Man as being the common ancestor.” (‘The early man and the rise of civilisation in Sri Lanka: Archaeological evidence’ -1992)

Over time the original community had spread across the country setting themselves up in rural parts of the country. Dambana close to Mahiyangana is considered the ‘capital’ of Veddah community while some had moved to the North Central and Uva Provinces and integrated with society.

Hunting and gathering has been their main occupation. They engage themselves in slash and burn cultivation and do some livestock herding as well.

In the modern era the name ‘Veddah’ is synonymous with Tissahamy. As head of the Veddah community he sought due recognition of his clan with much success. He maintained a constant dialogue with successive governments and was spokesman even at international level on issues related to indigenous people. His son, the present chief, Vanniya is considered a strong, tactful, sharp character compared to his father.

Around 300-350 families are estimated to be in around Dambana. While they are exposed to the present day pattern of living, they continue with their ancestral beliefs and rituals. They are proud of their dialect and insist on talking their language. However, with the assimilation into mainstream society it is anybody’s guess as to how long Sri Lanka’s ‘aadi vaasi’ will survive.