Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday, 19 May 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Diaspora is defined as the dispersion of people from their traditional homelands. There could be over 1.2 million Sri Lankan Tamils living in various parts of the world. The majority of Sri Lankan Tamils fled the country due to political and economic reasons. The number of Sri Lankan Tamils living abroad is even greater than the Tamils currently residing in the Northern Province.

Diaspora is defined as the dispersion of people from their traditional homelands. There could be over 1.2 million Sri Lankan Tamils living in various parts of the world. The majority of Sri Lankan Tamils fled the country due to political and economic reasons. The number of Sri Lankan Tamils living abroad is even greater than the Tamils currently residing in the Northern Province.

Tamil diaspora shaped the Sri Lankan political landscape through its financial and ideological support during the military struggle. Subsequently the term “Tamil diaspora” was associated with a negative connotation amongst majority of Sri Lankans. It was also perceived that the Tamils residing abroad had immense financial capacity and cared more about the Tamils residing locally.

Eight long years have passed since the end of the war and three years of Yahapalanaya (Good Governance) yet the diaspora seems sceptical about the happenings in Sri Lanka. Currently the diaspora’s comeback is most anticipated, yet they seem to be missing from the development agenda. Disappointments and frustrations are brewing internally, as diaspora lacks any interest to invest their hard-earned money into northern development.

At this crucial juncture, it’s vital to have a detailed understanding about the diaspora’s motives, potentials and barriers faced by them, regarding investments in north and east.

The Sri Lankan Tamil diaspora population is vastly spread across numerous countries, Canada, UK and France with significant concentrations. Prior to 1983, only a small number of Tamils left the country, largely due to professional and economic gains.

concentrations. Prior to 1983, only a small number of Tamils left the country, largely due to professional and economic gains.

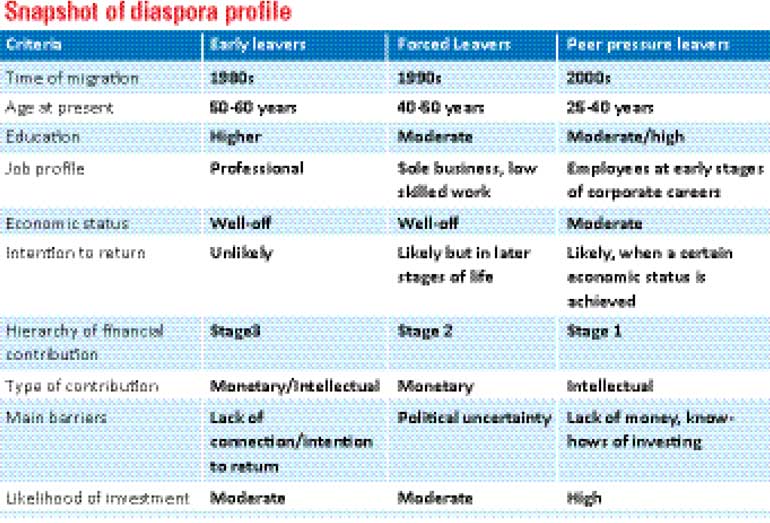

However, post 1983 the scenario changed and a large number of people started fleeing the country to escape the ethnic issues and civil war. Tamil diaspora population can be classified into three broad segments based on the period of migration. There could be few exceptions, but the intention is to give an overview about their profiles, especially regarding, investment capacity and likelihood of returning to the north.

Early leavers: the initial group which migrated during the 1980-’90s are the wealthy and affluent segment, working as professionals or in decent jobs within their host countries. This segment left early before the war intensified as they were already well-off, had connections abroad and wanted to secure a peaceful life. Now, they would be around 50-60 years of age and have established themselves within their respective host countries. Currently they have few/no connections in Sri Lanka.

Forced leavers: This segment was forced to leave the country during the 1990-2000s as the civil war intensified. The group was interdependent on each other, as the first to leave had to help his/her family members migrate. They found any means, even illegal avenues to escape from their home land which was rapidly transforming into a war field. This segment was largely unprepared and didn’t have proper education/qualifications during the time of migration. As a result, forced leavers suffered the most within both their home and host countries. Upon their arrival in the host country, some started working on their own sole proprietor business whilst others found employment in less skilled/blue collar jobs. Once settled, suitable marriage partners with similar background looking for opportunities to leave the country were sourced from north. Most of them are in the age group of 40-50 years of age currently.

Peer-pressure leavers: Migrated after2000. Tight procedures were in place during this time to prevent illegal migration and people started looking for alternate avenues, such as student/sponsor visas. This segment possessed fair educational/professional qualification, prior to migrating. They extended visas and secured employment upon completion of their higher education in host countries. Currently, they are at an early stage regarding profession, family life and trying hard to establish themselves within the respective countries they call home now.

Contrary to local belief, diaspora do not possess abundant financial capacity. Most importantly, they too have their own demanding priorities and commitments.

If observed closely, diaspora’s financial contribution to Sri Lanka can be summarised into a hierarchical order. The first stage of financial contribution came in the form of remittances sent to family members. The second stage includes rebuilding their belongings (renovating homes affected due to war) and acquiring assets for themselves in Colombo and the north. Only when these two stages are fulfilled, would the diaspora seek to invest in northern development to sustain their status quo.

Diaspora’s remittance contribution to the northern economy is significant. More than one-third of the houses obtained monthly remittance from the diaspora, backing up the excessive consumption capacity of the families residing in north. They have significantly contributed to meet the family’s household expenses, rebuild ancestral properties, purchase household equipment, vehicles, etc. There have been criticisms regarding the household’s easy access to money through remittance, as it has been one of the reasons for northern youth to not engage in any employment/employment creation.

A fraction of diaspora is investing efforts towards obtaining dual citizenship, mainly with the intention to purchase a property for investment and retirement purposes. The Department of Immigration and Emigration claims the Government of Sri Lanka has provided over 20,000 dual citizenships so far. Over the past few years, the diaspora has heavily contributed to the construction and real estate boom in Sri Lanka.

Diaspora would start looking for investment opportunities in Sri Lanka once their basic commitments/desires such as acquiring assets are fulfilled. Such types of people should be tapped to access the opportunity to translate the diaspora into potential investors. If an appropriate and reliable investment climate exists, the diaspora would look for further investment opportunities to meet their self-actualisation needs.

The diaspora’s investment interest is rather a complex situation, where they could be motivated with a mix of both financial and non-financial related components. The motivation to invest could be subdivided into Financial, emotional, political and social status related aspects.

The diaspora has been unrealistically perceived as a segment holding massive wealth within their host countries. However, large proportions are struggling to provide continuous financial support for their family members residing in the north.

As highlighted previously, the early and forced leavers could have the financial capability to invest. However, whether they have such an intention is questionable.

Peer-pressure leavers could adapt well within the growing tech start-up culture and provide intellectual support rather than a financial one. They can easily play a catalyst role in terms of transforming startups.

The popular belief that diaspora would permanently return one fine day remains as an illusion. Even diaspora plans of returning home as part of post-retirement plan might just remain a dream. As their generations are deep-rooted in the host country they increasingly feel a sense of disconnection as majority of their relatives/friends aren’t residing in Sri Lanka anymore. The diaspora residing in Western countries would not leave their host countries just like over 150,000 Sri Lankan Tamil diaspora residing in India, mainly in concentration/refugee camps. As they have become connected and started to accept their host countries as their own homeland.

The diaspora is also concerned about the political stability of the country just like any other investor. In addition to that, they are cautious about recovering investment and considering the risks involved. They have strong negative sentiments on political factors, as they once left the country empty-handed.

It’s a common scenario where Government/Provincial Council invites a group of potential investors for discussions, investment forums, followed by visit around Jaffna. However, the happenings beyond this point remain a mystery. Are these potential investors converted into investors? Are there any follow-ups? What are the KPIs established and achieved? It’s difficult to assess whether the potential investors are willing to proceed with next steps and establish without a formalised structure in place.

Besides the three key segments explained above, the second generation diaspora are increasingly concerned and interested in participating in the north and east development agenda. This group was born in or grew up in their host countries. Even though they are citizens of other nations, they have an emotional connect and desire to make an impact to help develop the north and east. Second generation diaspora is highly unlikely to return to Sri Lanka yet their intellectual contribution and the strong network of professionals can help rebuild the livelihoods of Tamils in Sri Lanka.

Harnessing the power of diaspora for the national development is essential for a country like Sri Lanka. The National and provincial government are organising events, investor forums, etc. in isolation to attract diaspora investments. These initiatives aren’t sufficient and fail to provide a comprehensive picture, thus resulting in limited impact.

All the efforts need to be integrated, with proper KPIs in place to measure progress effectively. Various countries around the world have a large diaspora population; tried and tested models to engage diaspora to the development of the country could be implemented. Sri Lanka certainly needs to have a rigorous approach towards attracting the diaspora for the development of the Northern Province.

(The writer is a Market Research expert specialised in demand-side estimation and segmenting consumers. He is the Head of Research at Sparkwinn, a market research agency specialised in studying consumer and social issues in Sri Lanka. He can be contacted through [email protected].)