Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday, 28 May 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

London (Reuters): Sri Lanka’s finances were fragile long before the coronavirus delivered its blow, but unless the country can secure aid from allies like China, economists say it may have to make a fresh appeal to the IMF or default on its debt.

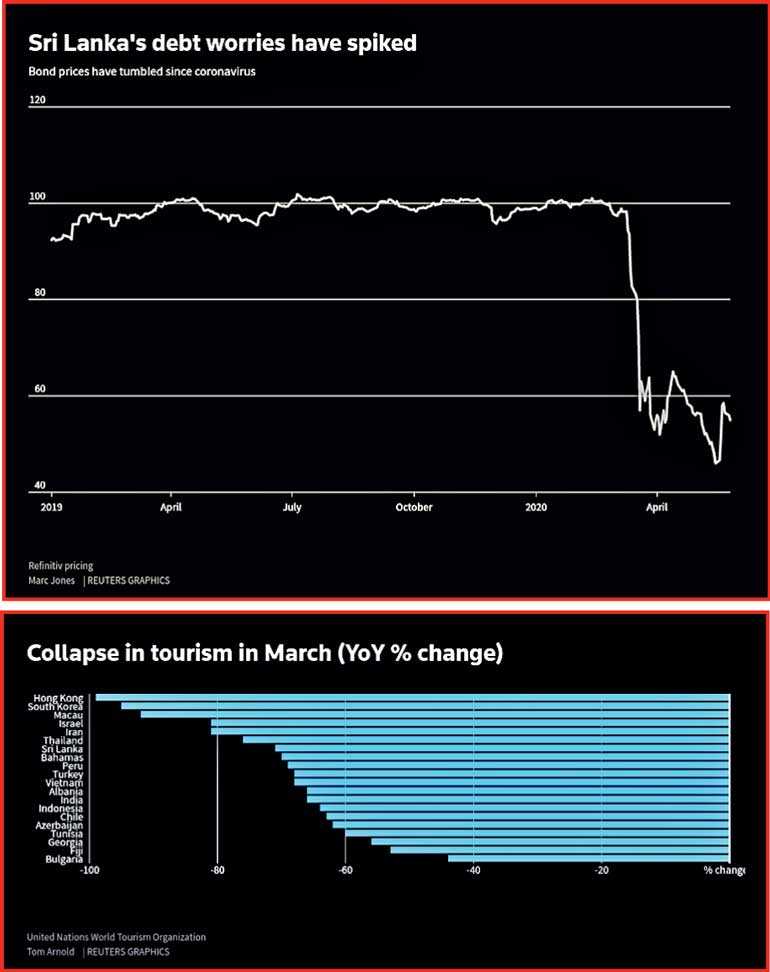

All the tell-tale crisis signs are there: a tumbling currency, credit rating downgrades, bonds at half their face value, debt-to-GDP levels above 90% and almost 70% of government revenues being spent on interest payments alone.

The IMF seems the obvious option — Sri Lanka has already asked the Fund for a ‘Rapid Credit Facility’ — but securing a new longer-term arrangement might not be straight forward.

The new Government veered off its soon-to-expire current IMF program late last year by slashing taxes, including VAT and the ‘nation-building’ tax brought in after the island’s long-running civil war in 2009.

In February, the IMF warned Colombo was set to miss its 2019 primary surplus target “by a sizable margin”, and the economic outlook has deteriorated dramatically since then.

Sri Lanka’s Central Bank sought to allay fears of a default in a statement last week, calling speculation “baseless” and vowing the country will “honour all its debt service obligations in the period ahead”.

External debt payments between now and December amount to $ 3.2 billion. Other costs could bring that up to $ 6.5 billion in the next 12 months, Morgan Stanley estimates, and with FX reserves of just $ 7.2 billion, it has described the situation as a ‘tightrope walk’. The crunch point looks likely to be a $ 1 billion international sovereign bond payment due in October.

“The market is pricing in the risk of a credit event there,” said Aberdeen Standard Investments’ Kevin Daly, pointing to the recent drop in some of country’s bonds to under 50 cents on the dollar and rise in borrowing costs to over 20%.

“If they were to seek an IMF funding program that would at least address some concerns, but let’s not forget the last fiscal measures sent the wrong signal.”

One view, dismissed by the Central Bank, is that delayed Parliamentary Elections may have hampered decisive policymaking, including how to navigate the economic hit from the pandemic.

Ratings firm S&P Global estimates that only recently-defaulted Lebanon spends a larger proportion of revenue on bond interest payments.

Add to that the hammer blow from the virus. Tourism, which accounts for nearly 12% of the country’s economy and 11% of jobs according to World Bank, has been floored again just a year after the Easter Sunday suicide bombing attacks.

IMF or bust?

Sri Lanka’s sizable textiles industry has been shredded too as global retailers shut up shop during lockdowns. Morgan Stanley forecasts the fiscal deficit will reach 9.4% of GDP this year, while a primary balance deficit of 3% of GDP would be more than 4 percentage points off stabilising debt levels.

“The room to kick the can down the road is not really there anymore,” said Mark Evans, an analyst at Ninety One, formerly Investec Asset Management.

Sri Lanka “probably has the capacity to service its debt obligations this year,” he added. “But much beyond that it becomes more questionable without a credible (fiscal consolidation) plan that could unlock IMF and other multilateral support.”

Other bilateral support could potentially come from China, especially as Beijing was a backer of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s elder brother Mahinda, who ruled the island from 2005 to 2015 and is now its Prime Minister.

With one of the deepest ports in the world, Sri Lanka has also long been a target of Beijing’s ambitious Belt and Road scheme, while regional power India has been vying for deals to counter China’s influence.

China’s foreign ministry didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment on the possibility of help. Sri Lanka’s central bank said last week it was engaging with “all investment and development partners”.

It is working on currency swap and credit lines with both India’s central bank and the People’s Bank of China and Beijing, and also seeking assistance from the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and other multilaterals.

Aberdeen’s Daly said any signals of debt help from China could trigger a relief rally in bond prices but IMF support was still likely to be needed and that would come with stringent conditions.

“They would have to do an about face to get an IMF program, but that is probably one of only things they can to address the concerns about debt sustainability.”