Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Thursday, 15 December 2022 03:35 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

|

Only a democracy re-load can prevent socioeconomically driven civil upheaval in 2023 by providing an alternative pathway. If the legal intervention spearheaded by Prof. G.L. Peiris on behalf of the combined Opposition (SJB, FPC, SLFP, TNA, with the JVP-JJB a significant absentee) to secure the local authorities’ election on schedule succeeds, and the electoral heart of Sri Lanka begins beating again healthily, the country will avoid another bloodbath and a fourth civil war, also saving the democratic system. If not, not.

2022-2024: An arc

2022 will not be known as the year that Ranil Wickremesinghe became President. It will be known as the Year of the Aragalaya, just as 1818 and 1848 were the years of the great rebellions against colonialism, 1953 was year of the great Hartal, 1971 was the year of the April Insurrection and 1976 the year of the nationwide student struggle (following the Weerasooriya shooting).

2022 is Sri Lanka’s equivalent of ‘1968’ which is known in contemporary world history as the year of youth revolt.

2022 dislodged a powerful President, Gotabaya Rajapaksa from office and overthrew the rule of the Rajapaksa oligarchy. It was an unfinished uprising –as many tend to be—and the year 2022 culminated in the selection by the retreating Rajapaksa clan, of Ranil Wickremesinghe as President. That abnormality, that distortion, cannot be normalised. President Wickremesinghe will almost certainly lose a presidential election in 2024, and is utterly unlikely to lead his government to an electoral victory at any level, local authorities, provincial or parliamentary, before or after that. The real question is whether he will have the wisdom to open the electoral safety valves as early as he can next year (2023) or will delay till he is forced by unremitting mass pressure to hold elections as the least bad outcome for him.

I perceive 2022-2023-2024 as comprising a single arc of struggle (‘Aragalaya’) albeit with different stages, phases, interludes, modes, emphases and tides.

2023 will be the year of serious social struggle against the Wickremesinghe presidency as it attempts to force the citizenry to swallow ‘bitter medicine’ without any popular consent through an electoral mandate to do so. In sum, 2023 will be the Year of Economic Resistance.

The struggle may not end politically in 2023, and may do so only in 2024, the year of the presidential election with a resounding defeat of the incumbent, but it will consist a single trajectory or dynamic of struggle going back to the 2022 Aragalaya.

‘Arthika Aragalaya’

Is there an austerity program, be it propelled by the IMF or a government’s own neoliberal proclivity, that has been successfully seen through by an unelected leader in the past quarter-century? Nope. Is there an unelected leader in a democratic country who has politically survived in the last quarter-century? Nope. And yet, against all evidence to the contrary, President Wickremesinghe hopes to do just that, survive and succeed.

In the absence of a scheduled local election in the presence of mounting economic hardship, President Wickremesinghe will face both a conventional political challenge in the form of the SJB, JVP and FPC, as well as an unconventional/asymmetric challenge from the FSP, JVP, IUSF, trade unions, peasant unions and the social movement in general.

Already, the proliferation of pickets in December 2022 exhibits an impressive range in the diversity of composition, from poor peasants to university professors, from university students to white collar workers. 2023 will witness an eruption of peaceful protests on at least five major issues, economic and political:

1. Taxes which hit the professionals, middle classes and small and medium entrepreneurs rather than targeting the top corporates.

2. The attempt to scrap/subvert existing land reform legislation and unleash corporate farming; the transfer of power to divisional secretaries to disburse Mahaweli lands.

3. Attempts to unilaterally scrap labour legislation.

4. Unilateral attempts to privatise higher education.

5. The failure to hold elections; the circumscription of civic space for protest and the repression of legitimate dissenters.

The intention of the Wickremesinghe administration to change both land and labour policy may bridge the gap between town and country, workers and peasantry, and lay the foundation for the realisation of that dream of every left movement: a worker-peasant alliance.

Given the intended or intimated policy of privatising and foreignising higher education, 2023 is likely to see not only a worker-peasant alliance but also a worker-peasant-student-alliance.

Add the anti-middle class tax policy and it is likely to be a worker-peasant-student-professional alliance.

The demonstrations this December have already shown a new phenomenon: cross-sector alliances.

The presidential policy of selling strategic national assets and profit-making state enterprises will add a nationalist/patriotic dimension to the resistance, broadening it out into what the Latin American left calls (in a bow to Antonio Gramsci) a “national-popular bloc”.

How will the military and police respond to peasant and worker protests when their families are themselves affected by the hardships that the protests are targeting?

How will the military, intelligence and Police hierarchy act towards the mainline democratic Opposition which it knows is the next—imminent—government and the authority upon which it will have to depend for its own security in Geneva and at accountability hearings overseas? Will its loyalty to Ranil Wickremesinghe and the Rajapaksas be higher than its loyalty to itself?

Agrarian agitation

Unlike in the rest of South Asia – most notably India and Nepal—Sri Lanka has never had peasant rebellions because of the prudent policies of successive administrations since Independence. In the year that we celebrate the 75th anniversary of Independence that may change, thanks to the myopic, polarising policy concerning land tenure and administration now being signalled by President Wickremesinghe.

The shocking ‘exceptionality’ of Ranil Wickremesinghe is evidenced by the fact that the peasantry which benefited from the Accelerated Mahaweli Project, a landmark achievement of the Jayewardene UNP, piloted by Minister Gamini Dissanayake, is protesting against a UNP President’s plans to divest power and responsibility from the Mahaweli Authority.

The UNP always nurtured its peasant base, beginning with the days of D.S. Senanayake. Ranil Wickremesinghe lost that base utterly at the parliamentary election of 2020. The ruling SLPP lost its peasant base with the lunatic policy on fertiliser of the Gotabaya administration. Thus, detached from its two traditional pillars, the UNP and the SLFP/SLPP, where will the vastly important peasantry go? What mode of mass activity will the peasantry which harvested votes for the UNP and SLFP/SLPP, switch to in the face of Ranil’s extremist economics?

There were two waves of progressive reform oriented towards the peasantry in the past half-century. These were Hector Kobbekaduwe’s Land Reform legislation of 1972 – Dr. Colvin R. de Silva’s 1975 follow-up prong being focused on the foreign-owned plantations—and Premadasa’s Presidential Task Force on Land Redistribution of 1990. Both waves were in the aftermath of, and responses to, the two radical left armed uprisings by educated rural youth, in 1971 and 1986-1989.

If President Ranil Wickremesinghe rolls-back these two major pieces of state policy he will radicalise the rural areas and peasant communities that were never radicalised before, while re-radicalising the educated rural youth—the stratum that rebelled while their peasant parents and villages remained dormant.

When the J.R. Jayewardene administration attempted to open up lands in Monaragala to foreign corporate farming, a strong spontaneous protest movement arose from among the peasantry of the area, which then attracted many left activists and was most successfully led by Chandrika Bandaranaike herself (as chairperson of the newly formed Sri Lanka Mahajana Party) in 1984.

President’s political defeat

Colombo is the hometown of both President Ranil Wickremesinghe and the Opposition leader Sajith Premadasa. Even with Wickremesinghe now in office, Colombo has remained Premadasa’s city. He commands the streets, Ranil commands the suits.

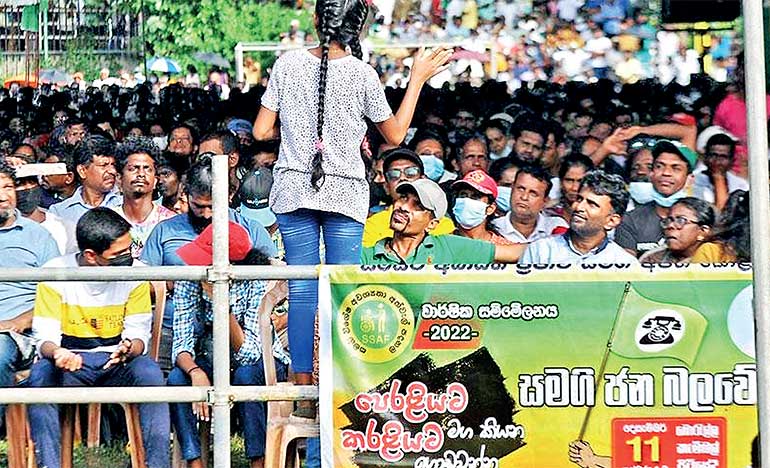

Wickremesinghe’s strategy of building himself a political base by encouraging defections from the ex-UNP Samagi Jana Balavegaya (SJB) collapsed in full public view with the TV news coverage of the impressive second convention of the SJB at the Campbell Park on Sunday, 11 December.

Ranil’s attempt to encourage collaboration on an ideological and policy basis (“we are the same, both rightwing”) failed too, with Sajith demarcating the SJB’s distinctive policy paradigm and the new party throwing down the gauntlet of open confrontation over the holding of elections, beginning with local authorities elections, next year.

Ranil’s third prong, of undermining Sajith Premadasa’s leadership by encouraging challengers, also crumpled pathetically, with young Premadasa clearly being the entrenched, unanimously endorsed leader of the main Opposition formation.

|

Sajith and SJB surge

Sajith’s speech and the SJB’s endorsed resolutions emphasised that if the local government elections are not held on schedule, then the party will return to the practice of mass mobilisation, taking it to the streets, without making that mode of action contingent “upon permission from the regime”. He recalled that before the Galle Face protests began on 3 April this year, the SJB had demonstrated at the Presidential Secretariat on 15 March and that the party had braved Police blockades and marched through Colombo in November 2021.

Premadasa passionately saluted the “Jana Aragalaya” in his speech:

“The Jana Aragalaya is relevant even today…There are a large number of youths imprisoned because of the citizens’ struggle. We will not only stand for them but also take charge of the Aragalaya that arose from the hurt, tears, pain and stresses of the people to launch a massive revolution to rebuild this country.”

The SJB’s National Organiser Tissa Attanayaka declared that 2023 will be the year of pushing for elections—including a presidential election.

Of the two national alternatives, namely the SJB and the JVP-JJB, only the SJB has so far articulated any big ideas which are easily understood in global terms. Avoiding extrapolation, I use below the terminology/phraseology contained in Sajith’s address to the SJB convention at Campbell Park:

1. “Social Democracy centred on a humanistic capitalism; social market forces for the purpose of generating wealth”.

2. Rejection of extreme capitalism and extreme socialism; a Middle Path, eschewing ideological extremes in economics. Rejection of “the notion of that free-market forces can solve all the country’s problems. This is incorrect. It requires government intervention, contribution, and strength.”

3. Restructuring loss-making enterprises “while retaining the ownership of the enterprise, and making the enterprise profitable through joint public-private partnerships and without mass retrenchment”.

4. Rejection of the notion that the public service is a negative factor. The public service is a valuable asset which must be protected but also reformed and modernised.

5. Rejection of the strategy of contraction of the economy and price rises of essential commodities and public services (electricity, water).

6. A “programme to eliminate all forms of poverty including income poverty, consumer poverty, investment poverty, unemployment, and high inflation through targeted programmes such as those implemented during the tenure of President Ranasinghe Premadasa.”

7. “Working to establish and protect not only political and civil rights, but also to make economic, social, religious, and cultural rights the basic rights of the people.”

8. Resolving the ethnic problem through maximum devolution within a united, undivided, unitary, single, sovereign country (“eksath, nobedunu, ekeeya, svairee, eka ratak thula”).

9. Law and order, justice and equality, zero-tolerance of corruption. Field Marshal Sarath Fonseka to head the suppression of corruption.

10.“No caste or class divisions”.

This can hardly be defined as rightwing or even centre-right, still less a neoliberal sibling of Ranil’s UNP. This is a centrist social democracy with a progressive populist appeal. Where Sajith Premadasa is coming from and the ground on which he has chosen to make his stand, was explicit:

“There are forces attempting to destroy the SJB. But as long as I, Sajith Premadasa, the son of Ranasinghe Premadasa am alive, no one will be able to harm the SJB.”

There were three (resoundingly applauded) invocations of President Premadasa in Sajith’s speech.

Dr. Harsha de Silva was correct when he observed in his speech at the SJB convention that “Sajith Premadasa is the only leader who has a grasp of, and the ability to grapple with, the complexity of the crisis and the necessary solution”.

The JVP-JJB’s AKD (and AKD’s JVP-JJB) fail to qualify. I would add that Sajith, with his grasp of the grassroots sentiment as well as of macroeconomics, has the best sense of a sustainable policy mix and its optimal balances and ratios.

New populist centrism

Following the Hartal of 1953, a victory for the UNP’s Sir John Kotelawala in 1956 ranged from wildly improbable to unthinkable. He was absolutely the wrong choice of Prime Minister in the aftermath of the Hartal of 1953. The writing on the wall spelled the victory of the emergent centrist-populist mainstream formation led by S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike.

Ranil Wickremesinghe was the wrong choice in post-Aragalaya 2022. His personality and discourse are as angular, jarring and polarising as those of Sir John. The electoral end of President Wickremesinghe in 2024 —if he is lucky enough to enjoy one—is a foregone conclusion.

Sajith Premadasa and his SJB have a considerable mass base. Like Sir John Kotelawala, Ranil Wickremesinghe has an elite fan-club but no mass base. The SLPP has a marginal, residual base. 2023-2024 must be regarded as in effect, a single year, a year of decisive struggle transitional to a Sajith Premadasa presidency and an SJB-led (SJB-FPC) government.

In 1956 the writing on the wall was invisible to the recalcitrant rightwing elite and the orthodox left opposition, just as their contemporary successors, ranging from professorial Trotskyists to left-liberals, post-modernists and neoliberals who thought it impossible for Premadasa to beat Sirima Bandaranaike in 1988 and the JVP in 1989, Mahinda Rajapaksa to defeat Ranil in 2005, and Mahinda and Sarath Fonseka to smash Prabhakaran’s LTTE in 2009, find it impossible to see that both Ranil’s UNP-SLPP and AKD’s JVP-JJB can and are likely to be beaten by Sajith and the SJB.

The blind-spot shared by the Right and Left is both attitudinal and theoretical-perspectival: the inability of the intellectual ‘constructs’ of the (elitist establishment) Right and the (non-Gramscian) Left to comprehend the protean phenomena—distinct though interactive—of populism and centrism.

I must confess that I am building on and extending a critique made over half-century ago by my father, Mervyn de Silva (aged 37 at the time) while reflecting on ‘1956’ in his multi-part think-piece “1956: The Cultural Revolution That Shook the Left” and “The Left Awakens from Romance to Reality”, full-page articles published in the Ceylon Observer Magazine Edition, 16 and 23 May 1967.

TNA-Ranil entanglement

It was authoritatively reported last Sunday that “...two major demands TNA would place were the need for self-determination and a federal form of governance.”

Most federal or quasi-federal systems do not have any mention of self-determination and many proscribe it. No Southern political party will agree to federalism with or without self-determination (or vice-versa). The overwhelming majority of the island’s citizens rejected both federalism and self-determination even when losing thousands of lives a week at the hands of the Tigers.

- Pic credit: Nisal Baduge