Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday Feb 13, 2026

Tuesday, 4 October 2022 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

It is a pity that the 22nd Amendment Bill fails to root out one of the most dangerous features of the current Constitution

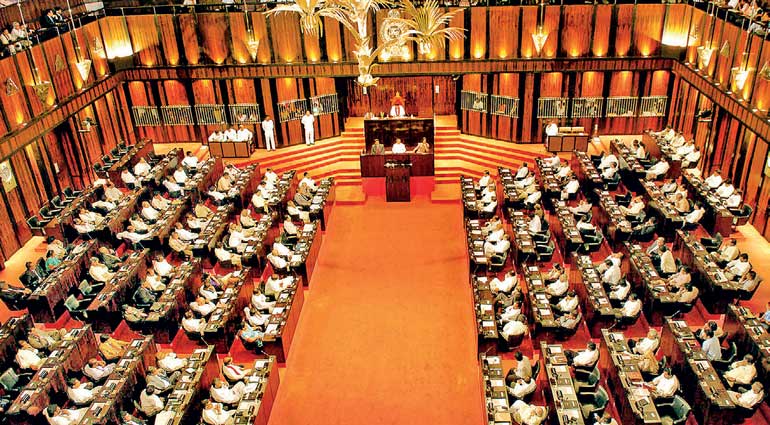

Parliament is about to debate the 22nd Amendment to the Constitution Bill this week. Among its features (both positive and negative), there appears to be one conspicuous gap: the ‘urgent’ Bill process is left untouched.

Parliament is about to debate the 22nd Amendment to the Constitution Bill this week. Among its features (both positive and negative), there appears to be one conspicuous gap: the ‘urgent’ Bill process is left untouched.

One of the most egregious elements of the 20th Amendment to the Constitution was the reintroduction of the ‘urgent’ Bill process. The 19th Amendment had in fact repealed Article 122, which sets out this process. Yet, the Article was reintroduced through the subsequent Amendment enacted by Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s Government.

Article 122 of the Constitution

Article 122 enables Bills that the Cabinet of Ministers considers ‘urgent’ in the interests of national security or disaster management to be fast-tracked. This Article contains two dire features.

First, it dispenses with the application of Article 78(1) of the Constitution, which provides: ‘Every Bill shall be published in the Gazette at least seven days before it is placed on the Order Paper of Parliament.’ If the Bill is deemed an ‘urgent’ Bill, however, it does not need to be gazetted in advance. That means the public, and even the Opposition in Parliament, may not get an adequate opportunity to scrutinise a Bill that is being fast-tracked through Article 122.

Second, Article 122 dispenses with the application of Article 121(1) of the Constitution, which enables a citizen to refer a Bill to the Supreme Court within one week of the Bill being placed on the Order Paper of Parliament. The Supreme Court would then determine whether any provision of the Bill is inconsistent with the Constitution. If the Bill is deemed an ‘urgent’ Bill, however, citizens would not have a one-week window to challenge the Bill.

Article 122 sets out an alternative process through which the Supreme Court may scrutinise an ‘urgent’ Bill. The President must first refer the Bill to the Chief Justice and require a special determination of the Supreme Court as to whether any provision of the Bill is inconsistent with the Constitution. The Supreme Court can then hear petitioners and respondents and, at its discretion, additional parties, and is required to make its determination within 24 hours (or such longer period not exceeding three days as the President may specify). It must communicate its determination only to the President and to the Speaker, who will read out the determination in Parliament.

The 22nd Amendment

The 22nd Amendment to the Constitution Bill (which would eventually become the 21st Amendment to the Constitution, if enacted), extends the period available to citizens to challenge ordinary legislation. That period would be fourteen days if indeed the Amendment is enacted. However, the Amendment does nothing to remedy the terrible process with respect to ‘urgent’ Bills, and leaves intact an opportunity for a Government to mischievously rush legislation under the guise of ‘urgency’ in the interests of national security or disaster management.

Transparency in the legislative process is a crucial feature of any functioning democracy. It is through a process of critical scrutiny that good legislation can be improved, and bad legislation avoided altogether. Sri Lanka does not possess post-enactment judicial review of legislation, and only provides an extremely narrow window of opportunity for the public, civil society, and the Opposition to scrutinise and challenge draft legislation at the pre-enactment stage. Yet, in the case of ‘urgent’ Bills, the new Amendment would fail to ensure even this narrow window of opportunity. Thus, it would fail to safeguard transparency in the legislative process.

Will the PTA’s replacement be an ‘urgent’ Bill?

The most obvious practical consequence of this gaping hole in the 22nd Amendment concerns the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA). Recall that the PTA was enacted in 1979 as a ‘temporary provisions’ law and was classed an ‘urgent’ Bill at the time. That gave the Supreme Court a mere 24 hours to scrutinise the Bill. Cabinet had also decided that the Bill would be enacted with a two-thirds majority in Parliament. The decision effectively meant that the Supreme Court was only required to assess whether the Bill was inconsistent with any of the entrenched clauses in the Constitution. The rest is history. 43 years later, we are still saddled with one of the worst security laws in the world.

The present Government has pledged to repeal the PTA and replace it with a new National Security Act. The relevant Bill, when it is ready, can very easily be deemed ‘urgent’ in the interests of national security. Therefore, there remains a genuine risk that the Government replaces the PTA with a new law that can be fast-tracked through the ‘urgent’ Bill process. A meaningful opportunity for the public to scrutinise any new national security legislation would be lost, and a repetition of a 43-year debacle becomes probable.

Apart from national security legislation, new cyber security and online safety laws might be rushed through the ‘urgent’ Bill process, as Cabinet’s views on what laws concern ‘national security’ may be highly subjective.

Dangerous and redundant

There is absolutely no rationale for using the ‘urgent’ Bill process to enact national security legislation in Sri Lanka. The claim that there may be a national security threat that requires a Bill to be enacted within such a short period of time, and with such opacity, is simply false. Sri Lanka already has a Public Security Ordinance, which enables the president to declare a state of emergency and promulgate emergency regulations. Any crisis can be dealt with through these broad powers. Unfortunately, we are accustomed to the routine abuse of these emergency powers – all the more reason national security legislation should not be fast-tracked through the ‘urgent’ Bill process.

The same rationale may be applied to the subject of disaster management, which is already covered by a Disaster Management Act. Tragically, the Sri Lankan Government neither used this Act properly nor enacted any new legislation through the ordinary legislative process when it encountered the COVID-19 pandemic. So, the case for enacting new laws in the interest of disaster management through an ‘urgent’ Bill process is weak and disingenuous.

It is a pity that the 22nd Amendment Bill fails to root out one of the most dangerous (and in some ways, the most redundant) features of the current Constitution. Parliament, and particularly, members of the Opposition, whose numbers might be important to forming the two-thirds majority needed, must insist that the new Amendment repeals Article 122, and rid us of the ‘urgent’ Bill process once and for all.

(The writer is an attorney-at-law and a senior partner at LexAG – Legal Consultants.)