Thursday Feb 12, 2026

Thursday Feb 12, 2026

Friday, 22 November 2019 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

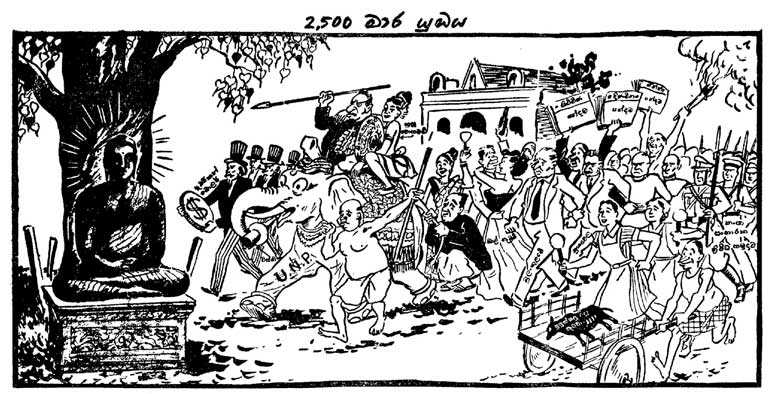

A poster from Sri Lanka’s 1956 Parliamentary Election stirring up ethnoreligious fervour by highlighting a perceived threat to Sinhalese Buddhism

The outcome of Presidential Election 2019 can be regarded as a miracle in the political sphere rather than an ordinary election victory of a political party. The prevailing view in Sri Lanka was that a Presidential Election could not be solely won on the vote of the majority without the support of minority communities. The Presidential Election 2019 can be considered the first time that this theory has been proven false.

The outcome of Presidential Election 2019 can be regarded as a miracle in the political sphere rather than an ordinary election victory of a political party. The prevailing view in Sri Lanka was that a Presidential Election could not be solely won on the vote of the majority without the support of minority communities. The Presidential Election 2019 can be considered the first time that this theory has been proven false.

In the 2005 Presidential Election, there were some close supporters of presidential candidate Mahinda Rajapaksa who argued whether the Presidential Election could not be won with Sinhalese votes alone. However, at that time there was a faction of the Muslim community supporting the SLFP. However, Mahinda Rajapaksa won the election narrowly owing to the policy adopted by Prabhakaran to boycott the election.

The Sri Lankan Muslims can also be considered an ethnic group that had actively contributed to the defeat of Prabhakaran’s separatist war. Not only did they act as a group which obstructed the cause of Eelam while living in the so-called Eelam territory, but they also joined the Government army as an ethnic group fighting Prabhakaran’s war effort.

Although there was a strong group of Muslim supporters in the UNP in the past, there was an equally powerful group that supported the SLFP from the time of Bandaranaike.

Abdul Nassar of Egypt and Ali Bhutto of Pakistan, who were powerful leaders in the Muslim world at the time, were strong supporters of Bandaranaike’s Non-Aligned Movement. During the regime of Sirimavo Bandaranaike, Saddam Hussein of Iraq, who was a powerful leader of the Muslim world and Muammar Gaddafi of Libya remained her most powerful supporters. Mahinda Rajapaksa was a leading figure in the Palestinian Solidarity Movement in Sri Lanka when he was a strong member of the Opposition and he had developed a close relationship with Yasser Arafat, the leader of the Palestine Liberation Organization.

At the time of the 2015 Presidential Election, the good relationship President Mahinda Rajapaksa had with the Muslim community in Sri Lanka had deteriorated considerably. It was a significant factor in the defeat of Mahinda Rajapaksa at the 2015 Presidential Election. The victory of the Yahapalana Movement at the 2015 Presidential Election was seen by the Sinhalese Buddhists in general and Buddhist monks in particular, as an instance in which the minority Tamil and Muslim communities of Sri Lanka had merged to defeat their war hero who had militarily overpowered the Tamil separatist insurgents.

Although the Easter Sunday attacks targeted Catholics and Christians, it caused equally enormous fear among Sinhalese Buddhists. The resignation of all Muslim Ministers in the aftermath of the Easter Sunday attack too had enhanced their doubt and fear. In the end, it can be presumed that they decided to defeat the influence of the minority, in a united action

After the civil war

An atmosphere was created in the aftermath of the internal civil war which was conducive to work closely with the TNA’s leaders. But President Mahinda Rajapakse did not want to take advantage of this opportunity. During the war, I had on two occasions spoken with the leaders of the TNA, including Mr. Sampanthan, about their problems. Though they had acted in compliance with Prabhakaran out of fear for him, they were in fact willing to see the movement of Prabhakaran defeated.

Mr. Sampanthan was of the view that the solution offered by Mahinda, who enjoyed great recognition among Sinhalese Buddhists, would be more acceptable to the Sinhalese Buddhists than a solution offered by a leader like Ranil Wickremesinghe, who did not share Rajapaksa’s popularity.

After the end of the country’s civil war, the TNA did something of symbolic significance. It used the Lion Flag, which Prabhakaran had banned for nearly 25 years, to decorate the hall, and the ceremony commenced with the singing of the national anthem. It can be considered a positive and revolutionary move, but unfortunately President Mahinda Rajapaksa was unable to understand the signal they gave or he may have been constrained from looking for solutions by political forces.

In the end, they resorted to solving their problems by adopting a policy to strongly support General Fonseka, the Opposition’s presidential candidate at the 2010 Presidential Election. They did the same thing in 2015 as well. Although they managed to defeat President Mahinda Rajapaksa, they were able to claim only a relaxed administration. They were unable to realise any of their political ambitions.

’56 Revolution

The victory of the Yahapalana forces in 2015 led to intense ethnic and religious divisions in Sri Lanka. While that victory may have produced a sense of relief to Tamils and Muslims, the Sinhalese Buddhists were deeply shocked and extremely displeased. The Yahapalana Government was unable to play any significant role in integrating the nation by resolving ethnic and religious divisions and building a modern nation. It had neither the courage nor the vision required for that. The passive approach of the Government in this context, invariably augmented the suspicions of the Sinhalese Buddhists, paving the way for the rapid growth of movements based on such impulses.

Even though the political manifestation of Sinhalese Buddhist discontent had only come to the fore at the 2019 Presidential Election, it can be considered the logical outcome of an organised process that had been brewing over a long period. It can be viewed as an instance where the electoral revolution of 1956 had been resurrected in a new form.

The 1956 election victory cannot be considered an outcome of a program implemented by S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike himself. What Bandaranaike did was to mount a Sinhalese Buddhist horse that had already been harnessed by a different pressure group and ride it to victory at the election.

The Buddhist Commission of Inquiry set up in 1953 can be considered as the background prepared by the public for this movement. It was a program implemented by a group of Sinhalese Buddhist leaders like Ven. Henpitagedara Gnanasiha Thero, Gunapala Malalasekera, N.Q. Dias and L.M. Meththananda. The hearings conducted and evidence recorded by the Buddhist Commission of Inquiry going to different places in the country had inspired the people and created enormous religious fervour among the Sinhalese Buddhists. Apart from that, the Buddha Jayanthi, the 2,500th anniversary of the passing away of the Buddha, which had been scheduled to be commemorated in 1956, and the Buddhist Commission of Inquiry set up in 1953 to inquire into the grievances of Buddhists, had stirred great religious fervour among Sinhalese Buddhists. It was a religious movement on one hand and a political movement on the other.

The book titled ‘Ceylon: Dilemmas of a New Nation’ by Howard Riggins, can be considered one of the best reviews of the ’56 Revolution. It can also be described as a unique book that analyses the grievances and emotions of Sinhalese Buddhists, their causes, their historical background and how the Sinhalese Buddhist Movement can be used for a political transformation.

Mara Yuddhaya: The war against evil

Nineteen fifty-six can be described as the election movement in which Buddhist monks had engaged themselves vigorously and actively in the politics of regime change. Even though there was a group of monks which had engaged in leftist politics before, this was the first time that all the temples in Sri Lanka had been used for politics.

According to Riggins, the Buddhist monks constituted the main political mechanism of the election campaign of the Mahajana Eksath Peramuna (MEP). Religion and language were the main slogans of the election campaign. The Buddhist Commission’s report was released when the announcement was made that Parliament was going to be dissolved and just 12 days before the actual dissolution of Parliament. The report was published under the heading ‘Betrayal of Buddhism’. This was an election campaign where the ingenious merging of traditional religious imagery had been used for contemporary political purposes.

Riggins’ analysis of a poster distributed during the election under the title ‘The 2500th Mara Yuddhaya’ is as follows: “A statue of the Buddha sat under the Bo tree at one end of the poster and the balance of the cartoon depicted a long parade led by Sir John Kotelawala on an elephant, the symbol of the UNP. Sir John Kotelawala was holding a spear pointed at the heart of the Buddha statue. Behind him on the elephant, sat one of his reputedly many girlfriends. In the parade that followed, some were ballroom dancing and drinking champagne, others were waiving the country’s principal newspaper, said to be in the party’s pay. In a Buddhist country, to kill meat is abhorrent; to eat is doubtful practice. In the foreground of the poster came a cart bearing the carcass of a dead calf to remind the devout of the shocking irreverence committed once by the Prime Minister who himself carried a barbequed calf in full public view.

“In the background several Uncle Sams held aloft large dollar signs. The poster was entitled ‘The fight against the forces of evil - 2500 years ago and now’. Underneath ran the caption: ‘In the year of the Buddha Jayanthi rescue your country, your race and your religion from the forces of evil’. The allusion was plain. Many temple pictures depict not dissimilar scenes, Mara, the mythical deity of evil rides on an elephant attacking the Buddha and his followers, and through the power of the Buddha’s purity and righteous ways Mara is confounded, the elephant falls and Mara is thrown to the ground where he is then helpless.” .

What policy could President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who came to power solely with the Sinhalese Buddhist vote, be pursuing in regard to this sharp division in the social system? Does he possess the capacity to serve as an exemplary leader capable of uniting a divided nation? Or will he adopt a partisan policy favouring only the Sinhalese Buddhists to the exclusion of other communities on the assumption that it is not his responsibility to look after the interests of non-Sinhalese Buddhists because he had come to power with the Sinhalese Buddhist vote alone, thereby creating a stalemate situation in the face of the ethno religious division? In this backdrop, the fate of the country rests on whether or not he is able to solve this complex puzzle

‘56 in a new way

In the end, the Sinhalese Buddhist movement was able to secure a massive political victory by defeating the Mara, in April 1956.

Gotabaya’s victory at the 2019 election can be considered a new version of the 1956 revolution. The defeat at the 2015 election had baffled the Buddhist forces. They saw this political phenomenon as a tragic moment where minority forces had gotten together and defeated the hero who saved the country and their religion. In this backdrop, temple-centred programs were initiated at the village level to disseminate the idea that the Sinhalese race and Buddhism were in danger and stressed the importance of Sinhalese Buddhists uniting to address the situation, which had resulted in the creation of a society where emotions based on race and religion reigned supreme.

Although the Easter Sunday attacks targeted Catholics and Christians, it caused equally enormous fear among Sinhalese Buddhists. The resignation of all Muslim Ministers in the aftermath of the Easter Sunday attack too had enhanced their doubt and fear. In the end, it can be presumed that they decided to defeat the influence of the minority, in a united action. This situation can be said to have given Gotabaya Rajapaksa, a huge victory. The Government as well as social and political critics had failed to gauge the reality of the situation as all these had taken place in temples all over the country and not on the public stage.

Although the election success can be considered a victory for Sri Lanka’s Sinhalese Buddhist, the division of the people along lines of race and religion will create major issues unless the victory gained is used for the common good of the people. Prabhakaran had a map demarcating the boundaries upon which the country would be divided. Coincidentally, the map showing the election results was almost similar to the map of Prabhakaran. A new feature added to it, is the hill country inhabited by plantation workers.

Some salient features of the election result

Many changes may take place along Sri Lanka’s future course following the result of the Presidential Election.

The UNP may shrink and decline. The survival of the JVP, which tried to come forward as a third force, may suffer major disruption. The inability of the JVP to secure at least a single vote in the Tamil-dominated North can be seen as a clear manifestation of the limits of their vision. While the vast majority of Sinhalese Buddhists act as a single group of their own, for their protection, the Muslims, Tamils and Upcountry Tamils also acted as separate groups of their own to settle their religious and ethnic grievances. In doing so, the Sinhalese Buddhists were able to achieve a landmark victory to their great satisfaction. The Tamils and Muslims could not achieve anything except defeat. The election result has left them bewildered and confused; now they are swirling towards a technical knockout.

What policy could President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who came to power solely with the Sinhalese Buddhist vote, be pursuing in regard to this sharp division in the social system? Does he possess the capacity to serve as an exemplary leader capable of uniting a divided nation? Or will he adopt a partisan policy favouring only the Sinhalese Buddhists to the exclusion of other communities on the assumption that it is not his responsibility to look after the interests of non-Sinhalese Buddhists because he had come to power with the Sinhalese Buddhist vote alone, thereby creating a stalemate situation in the face of the ethno religious division? In this backdrop, the fate of the country rests on whether or not he is able to solve this complex puzzle.

Sri Lanka is demanding an authoritarian leader like Lee Kuan Yew, not a democratic leader. Lee was able to make Singapore an advanced and developed country of the highest order by adopting a policy that helped build the nation, leaving no room for ethnic and religious conflict, which was accepted and respected by all. The volume of literature he had produced on this subject is huge. If the new President is able to learn from the lessons of Lee, that will augur well for the country as well as the new President.