Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Wednesday, 10 April 2024 01:20 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

What proved to be particularly effective were the ways in which the IDEAs conference explored how powerful states and capitals reproduce a highly unequal global order with dramatic regional differences

|

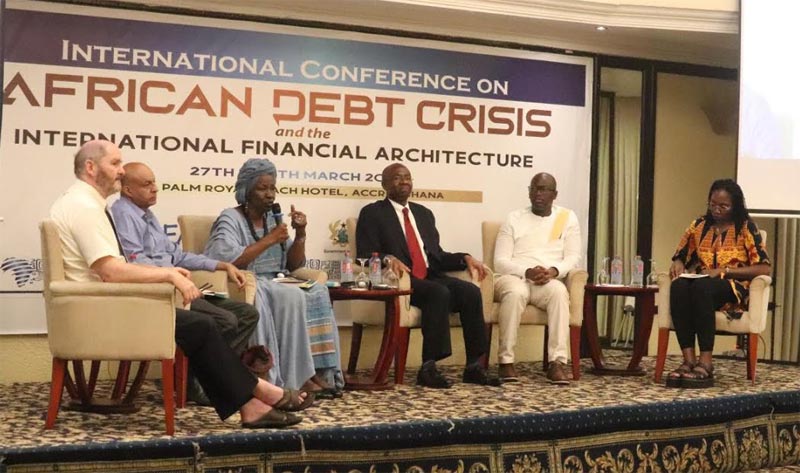

A recent conference convened by the International Development Economics Associates (IDEAs) network, titled “African Debt Crisis and the International Financial Architecture,” was held in Accra, Ghana from 27 to 29 March. It offered a stimulating platform for debate, tempered by the implicit background of the immeasurable suffering and equally heroic struggles Africa has witnessed.

A recent conference convened by the International Development Economics Associates (IDEAs) network, titled “African Debt Crisis and the International Financial Architecture,” was held in Accra, Ghana from 27 to 29 March. It offered a stimulating platform for debate, tempered by the implicit background of the immeasurable suffering and equally heroic struggles Africa has witnessed.

Participants were surrounded by reminders of Ghana’s role as both a key transit point in the Atlantic slave trade and its leadership under Kwame Nkrumah in the Pan-African movement that helped secure the independence of countries across the continent from European rule. Places near the conference venue – including Osu Castle on the coast and the Kwame Nkrumah Memorial Park and Museum – represented counterpoints in an ongoing conversation. How might African countries – and, by extension, the Southern periphery – break with the enduring structure of dependency?

In many ways, conference participants addressed this debate by taking up the issue of the current debt crisis and its transformation into a full-blown crisis of development. In Africa, as in many other places across the global periphery, working people have experienced tremendous pressure on their living standards with the cycle of monetary policy tightening in core countries in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, there have been a series of ongoing global shocks, from war to climate change. In response, the conference tied Africa’s burgeoning debt crisis to the call for a new international financial architecture.

Communicating across regional differences

What proved to be particularly effective were the ways in which the IDEAs conference explored how powerful states and capitals reproduce a highly unequal global order with dramatic regional differences, including between Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, and Asia’s periphery. These divisions require far more thinking about the demands and corresponding solidarity that can be generated by speaking directly to each region’s issues. For example, it remains difficult to imagine multilateral coordination to provide significant debt relief amid the current period of global chaos. But are there cross-cutting demands from the Global South that could gain traction, such as restricting commercial lending and expanding concessional loans to Low and Middle Income Countries (LMICs)?

It remains to be seen what form that this critical approach could take. At the conference itself, many proposals focused on reforming the system from within. For example, by curtailing the structural bias of international credit ratings agencies against many countries. But there is also a need to think more about the scope for promoting a new developmental vision. A programme that prioritises collective self-reliance will necessarily involve polarisation on the lines of a bloc of peripheral countries against metropolitan financial centres.

Such contestation could create far more policy space for developing countries to pursue their own domestic interests. This stands in contrast to the vicious cycle of external debt and austerity that they are currently enduring. In this regard, there was only so much that could be addressed even in the space of a multi-day conference. But these are themes with which we must continue to grapple as we think about the possibility of a different global financial system.

Africa’s burden of extraction

The IDEAs conference provided a compelling starting point by showing in an explicit way how Africa’s own destiny continues to be shaped by extraction that often occurs in a far more brutal way than even the rest of the global South. The extent to which commodity price dynamics contributed to the crisis was evoked in Grieve Chelwa’s presentation on Zambia, for example. According to World Bank International Debt Statistics, Zambia’s external debt stock more than doubled between 2012 and 2015, while international copper prices plunged by roughly half from a June peak in 2018 to March 2020.

Ndongo Samba Sylla brought in another dimension, noting that income transfers and resource theft (or plunder) account for a significant reduction in the primary income balance, which is a constituent part of the current account deficit. The fact that Gross Domestic Product (GDP) outweighs Gross National Income (GNI) in many African countries represents the degree to which even growth figures obscure the kind of extraction that occurs on the continent.

At the same time, senior economists reflected on their own experiences attempting to address these problems by reforming international institutions from the inside. As Yuefen Li noted, the debt relief provided to 36 countries under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative, mostly for African countries, cost $ 76 billion. But it was a drop in the bucket compared to the more than trillion dollars of external debt that the continent now carries. Yet as Jomo Kwame Sundaram argued in his presentation, the commitment of rich countries to expand concessional lending is far from being realised.

There are few actors to alleviate the resulting gap in development financing. Though not explicitly discussed by Sundaram in his own presentation, but a topic addressed by other speakers throughout the conference, China is a prominent exception. Nevertheless, its projects have also experienced greater scrutiny for both cynical geopolitical and justifiable reasons.

Meanwhile, as Sundaram put it, even the claim from the World Bank that the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) would provide the incentive to scale up lending “from billions to trillions” obscured the ways in which the new debt push has ended up compounding extraction through financialisation. A presentation by CP Chandrasekhar provided background to this argument. Chandrasekhar noted that the shift to commercial borrowing was the outcome of a change in supply side conditions within creditor countries since the 1980s. Money sloshed around and found new outlets, including the eventual explosion in the issuance of sovereign bonds by LMICs.

The origins of the recent debt crisis

In this context, the most recent African debt crisis has origins in a moment that demonstrates striking similarities with Sri Lanka’s own crisis. Specifically, after South Africa’s inaugural Eurobond issue in 1995 and Seychelles’ one more than a decade later in 2006, Ghana became the third Sub-Saharan African country to issue a Eurobond in 2007, the same year that Sri Lanka issued its first sovereign bond as well. After the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, countries in the core led by the US pursued what is known as ‘Quantitative Easing’, meaning accommodative monetary policy through Central Banks. The resulting liquidity glut meant that there was even more incentive for Southern governments driven by comprador elites to issue sovereign bonds and take advantage of investor interest in ‘Emerging Markets’.

But as Adebayo Olukoshi noted in a powerful opening keynote speech, the narrative of “Africa Rising” that became more prominent in the 2010s played on existing vulnerabilities. Money was channelled into areas such as financing (elite) consumption rather than helping the continent achieve its development objectives. Moreover, even if the money had been directed into productive sectors, the very terms of external commercial borrowing were stacked against the debtor countries. Speakers such as Jayati Ghosh alluded to the fact that Finance Ministers are routinely compelled to check the spreads on the bonds that their countries have issued in international capital markets, which are determined by the international credit ratings agencies. The process has meant that these Ministers’ priorities were always going to be focused more on the interests of external creditors rather than their own populations.

Alternative proposals

Like any productive discussion, the IDEAs conference raised more issues than it could resolve. In this regard, while many participants generally shared a similar perspective on the dynamics driving the debt crisis, especially financialisation and the resulting complexity of the creditor profile, the solutions varied. Some argued for more reforms within the system, including attempting to shift the process of debt restructuring away from the IMF to a supposedly more democratic space such as the UN. Others pointed to measures that appeared to imply a more explicit confrontation between creditor and debtor countries, including the need to form what Chandrasekhar called “debtors’ cartels.” Sometimes these demands overlapped within the same presentation.

But the real question is whether even with significant debt relief, including debt cancellation, the underlying trajectory of dependency can be altered. As the HIPC Initiative itself demonstrated, in the absence of a real break with the extractive model that dominates the continent, African countries will likely continue to find themselves facing recurring debt crises. In this regard, the conundrum implied by debt relief is not whether “corrupt” governments would take advantage of such an initiative. Rather, it is a matter of whether any renewed programme for relief anticipates a much bigger rupture, clearing the way for an alternative development vision.

|

Engaging Sri Lanka

In the lead up to the IDEAs conference, Ahilan Kadirgamar in his Red Notes Column titled ‘African Debt Crisis and lessons for Lanka’, (https://www.networkideas.org/featured-articles/2024/03/african-debt-crisis-and-lessons-for-lanka/) argued that these debates have relevance for countries outside of Africa such as Sri Lanka that are also experiencing debt distress. As conference participants clearly showed when analysing the African debt crisis, it is utterly ineffective to discuss the breakdown of an individual country without also tracing its global origins. In this regard, the conference offered crucial qualifications to remedies that begin from flawed assumptions, which are eagerly embraced by Sri Lanka’s own establishment.

As former senior IMF economist Peter Doyle pointed out in his presentation, for example, even the IMF’s country targets for the primary balance – meaning, government revenue and non-interest spending – are often unjustifiable. They lead to severe underperformance in growth of GDP per capita. As Doyle put it, where tax systems are weak, deficits are more than justified. In general, the lower the levels of a country’s GDP per capita, the more it should borrow in its own currency to help achieve its own development objectives. Nevertheless, the parameters of such borrowing remain an open-ended question. The conference was a space to critique decades of financialisation, while several participants alluded to the need for an alternative development model driven by state-backed domestic credit.

Dzodzi Tsikata framed the effects of the intervening debt crisis in Africa in stark terms that are applicable to Sri Lanka’s own context. She emphasised the “intergenerational damage” that is now occurring, further reflected in the extent to which debt servicing costs reduce the fiscal space for social spending. While our own establishment in Sri Lanka talks about the need to raise revenue, the other side of austerity is completely overlooked. Namely, the severe cutbacks to subsidies and other social expenditure that have resulted in a dramatic regression in people’s living standards. Issues such as child malnutrition have an irreversible, long-term impact that cannot simply be alleviated when new funding becomes available.

Even if Sri Lanka is eventually able to “successfully” exit the IMF program, the question is, at what human cost? The paucity of discourse about a short to medium-term relief strategy to cope with the immiseration of working people during the depression is an indictment of our ruling class. But considering the views expressed at the IDEAs conference, it further reflects tremendous short-sightedness in ignoring the paradoxes that have provoked serious researchers elsewhere. They have considered the impact of debt crisis not only on the infrastructure gap but also on human development.

Insights from Sri Lanka

Nevertheless, in its own way, Sri Lanka also offers us the possibility of cultivating a more explicit perspective on self-sufficiency. Meaning, incorporating production with consumption for the purpose of strengthening intersectoral linkages within the domestic economy. Such a strategy, towards which several presenters gestured at the conference, in fact requires a much stronger emphasis on redistribution. Given Sri Lanka’s own great revolt of 9 July 2022 and the subsequent repression, there is an incipient yet powerful awareness of the degree to which the IMF conditions are tied to an intense political process of counterrevolution. It is attempting to block a real alternative.

In this way, Sri Lanka affords an opportunity to sharpen debate about the macroeconomic issues raised at the IDEAs conference. The event provided the necessary basis for inter-regional comparison by exploring the complexities of the African debt crisis with lessons for the rest of the world. But there is an urgent need to disaggregate the effects of the crisis, especially at the household level. In the context of Sri Lanka’s own malaise, working people are being pressured to absorb the costs through impossible choices. They are forced to make grave decisions about whether to send their children to school or put food on the table. The proposed austerity solution to Sri Lanka’s crisis has the unintended effect of helping clarify the class nature of the breakdown.

Returning to struggles

A similar political perspective remains necessary for addressing the debt crisis around the world. Considering the relevance of Nkrumah’s legacy for the IDEAs conference venue, it is also important, as Walter Rodney articulated in an address to the Sixth Pan-African Congress in 1974, to keep alive the question of the degree to which states are shaped both by the interests of their own ruling classes and struggles on the ground. Fifty years later, as we consider the contemporary need for a debtors’ cartel, we must identify the persistent interaction between global and national patterns of inequality.

Or as Rodney argued: “Obfuscation of the notion of class in post-independence Africa has made Pan-Africanism a toothless slogan as far as imperialism is concerned, and it has actually been adopted by African chauvinists and reactionaries, marking a distinct departure from the earlier years of this century when the proponents of Pan-Africanism stood on the left flank of their respective national movements on both sides of the Atlantic. The recapture of the revolutionary initiative should clearly be one of the foremost tasks of the Sixth Pan-African Congress.”

Brusque though it may be Rodney’s injunction remains critical for reflecting on the ways in which the current global debt crisis compounds domestic inequalities. Accordingly, the IDEAs conference was an important starting point for galvanising debate about a set of issues that has acquired renewed urgency, in Sri Lanka and elsewhere.