Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Monday, 31 December 2018 01:12 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Despite all the progress made in the Great War to develop aircraft and engines, significant issues still remained. Even the improved larger aircraft could not fly very far with a significant payload of passengers and cargo. Frequent stops were required and the engines were notoriously unreliable, causing the need for many unscheduled landings.

As has been discussed in these columns, the Germans were early pioneers of Airships – large rigid structures filled with hydrogen gas (or inert helium if it was available) making these machines “lighter than air”. These craft were used for the first-ever scheduled air service even before the Great War. The Germans used them as bombers capable of reaching Britain, but they proved vulnerable to attack due the flammable hydrogen gas contained in the structure.

Great progress was made in the size and capability of these machines post WW1 and for much of the 1920s and ’30s they were seen as the future of long-distance air travel. Though considerably slower than fixed-wing aircraft, airships could stay aloft for long periods and the engines were needed only for propulsion, not to provide lift – the ‘light than air’ gas that filled the structure provided the lift.

Such was the dominance of the airships, that the Empire State building in New York was designed with an airship docking tower on its roof – the distinct spike that makes the building very recognisable but has never been used.

British R-series Airships

The British Government too was very keen on developing long-range airships. While the Dutch airline KLM was forging ahead with long-distance aircraft flights to Asia, using the same aircraft with crew changes en-route, Imperial Airways still used a mix of different aircraft and occasional train journeys to patch together the journey between Britain and Australia.

Much of the official Government effort in Britain was channelled into an ambitious airship program under the Imperial Airship Scheme. Two large airships, the R-100 which was privately funded and R-101 under Government funding, were being built in the late 1920s. With a length of 730 feet (223 metres) the R-101 was longer than three Airbus A380s placed nose to tail.

So confident was the British Government that the project would succeed that a huge hangar was built in Karachi (then part of British India) which was the final destination. The distinctive mooring mast made it a landmark for many years, though it was never used.

After only one test flight, the R-101 embarked on its maiden voyage to Karachi on 4 October 1930 with 53 crew and passengers on board. The next day it crashed in northern France, killing 48 of its occupants. That was the death knell for the British passenger airship initiative, it was abandoned soon after.

The Zeppelins

Germany forged ahead with its airship designs still called Zeppelins. With bitter lessons learned during the Great War, these were initially designed to be filled with helium, an inert gas that did not catch fire, unlike the easily flammable hydrogen. However, the USA had a monopoly on producing helium and in 1925 Congress passed the Helium Act which banned the export of this commodity.

Since an accidental hydrogen fire had never occurred on an airship, the Germans continued with the Zeppelin program. The largest-ever build was the Hindenburg completed in 1936, was 804 ft. (245 m) long and was powered by four Daimler-Benz diesel engines driving propellers. Designed to carry 70 passengers and 40 crew members, the Hindenburg had two decks with passenger quarters, dining rooms, promenade windows and other luxuries that were more reminiscent of cruise liners than aircraft.

Commercial services across the Atlantic commenced in 1936, with the Hindenburg making 10 round trips from Frankfurt to New York and seven to Rio de Janeiro during the first season, carrying over 2,700 passengers and covering 308,000 km that first year.

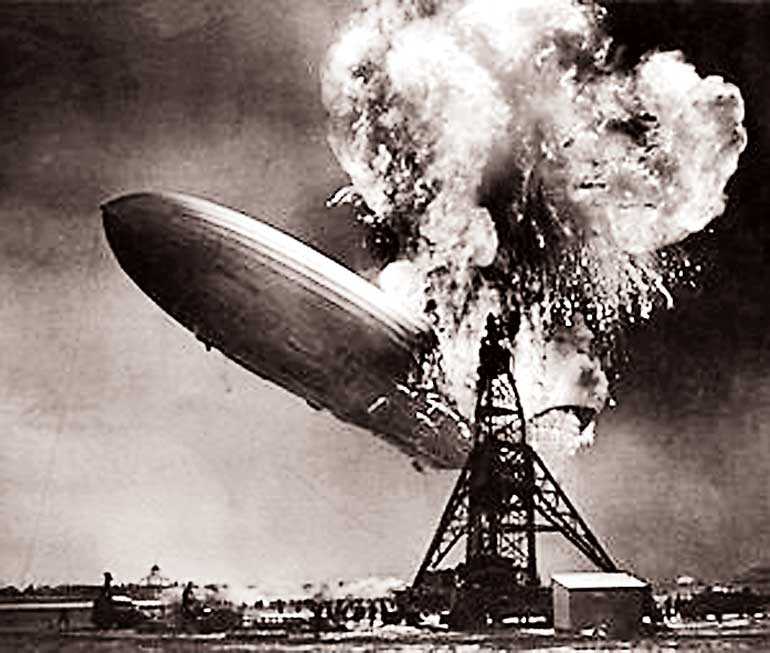

But on just the second flight of the 1937 season, the Hindenburg was consumed by fire while attempting to dock near Manchester New Jersey. Of the 97 people on board, 13 passengers and 22 crewmen died in the fire.

The actual cause of the fire has been the focus of much speculation. There are persistent claims that sabotage was the root cause, but this was never proven or officially acknowledged. However, public confidence in airships was shattered as the disaster was filmed as it occurred and seen worldwide by thousands.

With long range flights in fixed-wing aircraft which were much faster than airships (though much more cramped) becoming more and more routine thanks to the pioneering efforts of Pan American, KLM and other airlines, airships were no longer used for passenger or cargo purposes.

Today, other than the well-known Goodyear Blimp, used to telecast many sporting events in the USA, airships are no longer in widespread use. The Zeppelin company re-formed in the 1990s and built five prototypes, some of which are still flying, but was not a commercial success.

Conventional heavier-than-air flying machines appear to have prevailed as the most efficient, safe and scalable technology.