Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Thursday, 5 May 2022 01:24 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The biggest threat to sustainable land management comes from the belief that land is infinite, that it is a standalone resource with no interdependencies and that it can be bent to the will of human beings

|

In modern economics, land is broadly defined to include all that nature provides, including minerals, forest products, and water and land resources. While many of these are renewable resources, no one considers them “inexhaustible”

– Britannica

This is an introductory article, the first of five, on issues that impact on sustainable land management in Sri Lanka. These articles were prompted by the populist misinformation peddled by politicians and their cohorts that whatever they have done as land management has been to ensure food security in the country and for ‘development’ projects while encouraging foreign direct investment. This is a totally misguided and disingenuous propaganda as land management practiced in many instances have been purely for short-term profit, compromising the very essence of environmental security and long-term sustainable development.

This is an introductory article, the first of five, on issues that impact on sustainable land management in Sri Lanka. These articles were prompted by the populist misinformation peddled by politicians and their cohorts that whatever they have done as land management has been to ensure food security in the country and for ‘development’ projects while encouraging foreign direct investment. This is a totally misguided and disingenuous propaganda as land management practiced in many instances have been purely for short-term profit, compromising the very essence of environmental security and long-term sustainable development.

These articles will demonstrate the ill-effects to the environment and its biosecurity because of policies followed so far and how irreparable it can be and has been to the country’s environment and land sustainability. They will also emphasise the urgent need to develop a coherent land management policy via a process of broad stakeholder consultation along with a strong institutional and legislative framework for its effective implementation.

The attention on policy development by independent professionals has been given a fillip thanks to the recent economic and political upheavals, and while those issues take centre stage in people’s minds and the news media, it is of importance that attention must be given to what sustains every living being in the country, land.

This article which is being published in two parts, and a series of follow up articles on key elements associated with land which will be published, will present material for discussion and debate amongst professionals, academics, politicians, business leaders and the general public on a sustainable land policy.

In developing a futuristic, sustainable land management policy, many factors that impact on land management must be taken into consideration. Amongst all such factors, climate change rate is one of the major long-term factors that needs to be considered. It is the overarching factor that affects the entire Earth, not just Sri Lanka, but its impact may be mitigated to some degree if measures are taken by every country including Sri Lanka to lessen this impact. Not doing so will subject future generations to great peril and they will no doubt blame the present generation for their inaction. Political expediency, short-term gain, unbridled avarice, and not having the intelligence to see beyond their noses have stood in the way of taking necessary action. Politicians of all persuasions have been and still are at the top of this murky heap.

The complexity of climate change and the factors that bring it about need to be understood first to bringing in mitigatory factors. Some factors that affect climate change are phenomena beyond man’s control, but some key ones are within the ambit of man as they have been created and worsened by man. This series of articles looks at the situation in Sri Lanka and the factors that have and are contributing to climate change and the sustainability of land, not just to sustain mankind but to sustain the entire environment that in turn sustains human beings and all other living things including plants. The following topics will be covered:

These articles will hopefully lead to ideas for a long-term policy framework that takes in the key aspects associated with land and which are integral to sustainability of land.

It is hoped that these articles and the ideas presented will be the subject of discussion and debate amongst the public and all key stakeholders who are critical to the eventual formulation of a policy. It is also hoped that the media will provide the platforms that are needed for constructive, futuristic discussions on the formulation of a policy that will sustain many future generations.

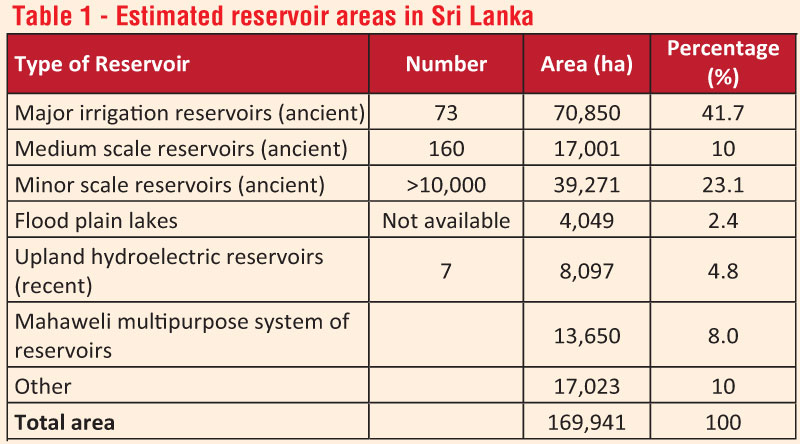

As a matter of interest, to demonstrate the futuristic thinking of the country’s ancient rulers, it is interesting to note that as per the Table 1, 74.8% of the reservoir areas in the country have been classified as “ancient”*, demonstrating that the country should owe its gratitude to the country’s ancient rulers for providing this resource to the generations that followed them and to the present, and future generations too. In this context, one must question whether less ancient rulers have contributed in a comparable manner and whether they entirely relied on the work of their ancestors to sustain agriculture and therefore the people of the country. *(Source: MENR and UNEP 2009 – http://www.wepa-db.net/policies/state/srilanka/overview.htm)

These articles will not be presented as academic exercises but as material that would hopefully generate an interest and a discussion that would lead to a better understanding on factors that impact on land management. It is hoped that such an understanding will lead to planners and decision makers realising the need for a long-term, inclusive policy on land management.

What is the biggest threat to sustainable land management?

The biggest threat to sustainable land management comes from the belief that land is infinite, that it is a standalone resource with no interdependencies and that it can be bent to the will of human beings. The wider and deeper meaning of “land” would be best summed up by the saying “we are the land, and land is all of us and everything around us. Land nourishes us and sustains us. We must nourish and sustain the land, if not, we will perish along with the land”. This sense of infiniteness, coupled with hardly an understanding as to what biodiversity means, forms the twin overriding threats to the future of sustainable land management.

Professor David Macdonald of the Oxford University describes biodiversity as the “variety of life on Earth, in all its forms and all its interactions. If that sounds bewilderingly broad, that’s because it is. Biodiversity is the most complex feature of our planet and it is the most vital. Without biodiversity, there is no future for humanity.” Biodiversity will be discussed in more detail in another article.

Aborigenes and their approach to land management

Aborigenes, defined by the Collins dictionary as the original inhabitants of a country or region who has been there from the earliest known times, were the opposite of today’s humankind when it came to sustainable land management. The journal Science Daily in an article published on 5 November 2019 on the Aborigenes experience in Australia (What we can learn from Indigenous land management – Lessons from first nations governance in environmental management) states, quote “as large-scale agriculture, drought, bushfire and introduced species reduce entire countries’ biodiversity and long-term prosperity, Indigenous academics are calling for a fresh look at the governance and practices of mainstream environmental management institutions”.

The article goes on to say that Aboriginal Australians’ world view and connection to country provide a rich source of knowledge and innovations for better land and water management policies when Indigenous decision-making is enacted, the researchers say. Incorporating more of the spirit and principles of Aboriginal and other First Nations people’s appreciation and deep understanding of the landscape and its features has been overlooked or sidelined in the past – to the detriment of the environment.

A common feature amongst Aborigenes throughout the world on what they identified as “Land” was that they, along with other living species, plants, and animals, and very essentially water, fire, their spirits, were a whole, inseparable from the different parts, and therefore interdependent.

The “whole is greater than the sum of its parts” – Aristotle

Over the years, with the “advancement” of civilisation, and the growth in population, the assumption of infiniteness of the resources and the notion that the sum of individual parts rather than the whole assumed greater importance. Aristotle who coined the phrase may not have had land management in mind at the time, but the principle he outlined is as valid today as it was then.

A long-term, sustainable, environmentally-friendly land policy framework that links interdependent components is unquestionably of paramount importance for the present generations and many more generations to come. Since independence, the land policy of the country has been developed and driven by political parties in government, and the changes of governments have witnessed changes to whatever policies introduced by preceding governments, and the fracturing of policies, and short-term gain taking precedence over long-term benefits.

Land and its fertility, provided it is well-nurtured, has a far greater life span than the fauna and flora that inhabit it, and essentially the water that sustains all of it, with a clear interdependence for sustainability of the whole. The whole is essentially greater than the sum of individual parts. This is an essential principle that must underpin a policy on land management.

The present state of land in Sri Lanka, where there is ineffective and inefficient use of it for agriculture, exploitation of natural forests that are hundreds of years old for its timber, the shrinking of space for wild animals, and the adverse and irreparable impact on biodiversity have all had a damaging impact on the environment and on land management. Besides this, ineffective water resource management, the deterioration of water quality, and not maximising economic opportunities, among other things, have led to questions about the advisability of short-term policy planning arising from the very nature of the country’s democratic governance model.

Unfortunately, this short-term mind set has influenced many others, including bureaucrats, and short-term gain has become the culture that defines many Sri Lankans.

Besides this, land policy has traditionally been developed in narrow vertical silos, and not from a broader context of what land would be without a policy on other essential, related components. Essential and integral parts of an overall land policy, such as a policy on water management, sustainable economic opportunities on both land and water, life sustaining biodiversity, forest cover, space for and protection of wildlife, and very importantly, overall environment management, energy management, waste management, etc., have been handled separately to the detriment of overall land management. Crucially, land management for climate change mitigation has received very little attention so far.

This policy document looks at land in a more holistic perspective, and on a long-term basis. Use of land for agriculture and other commercial purposes is considered from the prism of the most effective and efficient use of land, where “land” is considered from a broader perspective as outlined earlier.

The principle of a greater output using less land underpins the policy framework as land is finite and opening more land for cultivation and other developmental needs is not an answer to produce more.

The development of this policy document via these articles emphasises on the need for research and development to be the foundation on which the country’s land policy should be built and managed.

Such a foundation is considered essential if the long-term sustainability of the broader composition of what constitutes “land” is to be ensured for the benefit of future generations.

A land policy must essentially be long term, at least 10 to 20 years and not restricted to political governance cycles of five or six years. The proposed long-term land policy framework of a minimum 10 years, preferably 20 years duration, with bi-partisan political support and the support of other stakeholders, will better assure the continuity of land management policy irrespective of changes to governments.

A key recommendation arising from this land policy framework is to conduct a set of zone-based pilot studies in partnership with the private sector and research entities that would assist in developing specific, accountable policies within the overall policy framework.

The policy framework development process has considered the following key areas and examined available research work done in each area. These will be covered in more detail in the following four articles.

|

Demographic information

All economic and socio-economic policies and a policy on land management must be linked to current and future demographic projections, not just Sri Lanka’s, but more broadly global projections, particularly where such projections have the potential to impact on Sri Lanka. The past and latest statistics available would be a good basis to undertake such a projection. Demographics linked to land, food security, water resources and environmental factors must surely be a major factor in any policy setting whether it is on land, health, or economics. The finiteness of land makes it even more important to link it to demographics and to project different planning scenarios.

According to the 2012 census the population of Sri Lanka was 20,359,439, giving a population density of 325/km2.

The population had grown by 5,512,689 (37.1%) since the 1981 census (the last full census), in approximately 40 years with an annual growth rate of 1.1%. 3,704,470 (18.2%) lived in urban sectors – areas governed by municipal and urban councils.

5,131,666 (25.2%) of the population were aged 14 or under whilst 2,525,573 (12.4%) were aged 60 or over, leaving a working age (15-59) population of 12,702,700.

The sex ratio was 94 males per 100 females. There were 5,264,282 households, of which 3,986,236 (75.7%) were headed by males and 1,278,046 (24.3%) were headed by females.

The Asia Society publication “The Future of Population in Asia; Asia’s Aging Population” (http://sites.asiasociety.org/asia21summit/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/Asias-Aging-Population-East-West-Center1.pdf), states that Sri Lanka’s population is aging faster than any other nation in South Asia and has the fifth highest rapidly growing population of older people in Asia after China, Thailand, South Korea and Japan. In 2015, Sri Lanka’s population aged over 60 was 13.9%, by 2030 this will increase to 21% and by 2050 this number will reach 27.4%. Sri Lanka’s rapidly growing older population has ignited concerns of the socio-economic challenges that the country will face because of this.

These demographic factors must be considered when developing a land policy, as food security, and land and water-based economic opportunities and sustainability of these opportunities have a direct relationship to demographic factors and projections.

(Raj Gonsalkorale, MBA, is an International Management Consultant, Janendra De Costa, BSc (Agric) PhD, a Senior Professor and Chair of Crop Science, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Peradeniya, and Vijith Gunawardena, BA, a Land Management Practitioner.)