Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Monday, 13 December 2021 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

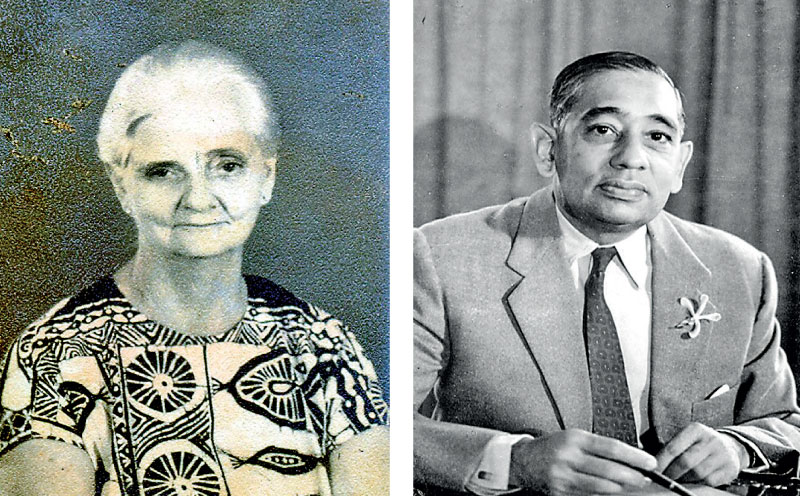

Dr. Noel Bartholomeusz and Nora Bartholomeusz

The 50th anniversary of the College of Surgeons of Sri Lanka was celebrated recently with an International Medical Conference attended by surgical associations of all SAARC countries, The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow and The Association of Surgeons of Malaysia. The delegations were physically present headed by the presidents of surgical associations and societies of the countries. The event also saw the presentation of the inaugural Dr. Noel Bartholomeusz Oration by Consultant Surgeon Prof. Mohan de Silva, Emeritus Professor Surgery, former Dean of the Faculty of Medical Sciences University of Sri Jayewardenepura and former Chairman of the University Grants Commission. It was presided over by CSSL President Prof. Srinath Chandrasekara and the Chief Guest was Prof. A H Sheriffdeen. Following is the oration:

The 50th anniversary of the College of Surgeons of Sri Lanka was celebrated recently with an International Medical Conference attended by surgical associations of all SAARC countries, The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow and The Association of Surgeons of Malaysia. The delegations were physically present headed by the presidents of surgical associations and societies of the countries. The event also saw the presentation of the inaugural Dr. Noel Bartholomeusz Oration by Consultant Surgeon Prof. Mohan de Silva, Emeritus Professor Surgery, former Dean of the Faculty of Medical Sciences University of Sri Jayewardenepura and former Chairman of the University Grants Commission. It was presided over by CSSL President Prof. Srinath Chandrasekara and the Chief Guest was Prof. A H Sheriffdeen. Following is the oration:

|

Dr. Noel Bartholomeusz

|

I am deeply honoured to be invited to deliver the first Dr. Noel Bartholomeusz Memorial Oration. At the outset may I offer my most sincere thanks to Prof. Srinath Chandrasekara, our President, and the Council of The College of Surgeons of Sri Lanka?

Naming an oration to the memory of a personality indicates the uniqueness of the person and in this instance a unique couple who lived more than four decades ago in this island. When trying to dig into the background of this great surgeon I came across this beautifully-crafted manuscript titled ‘Reflections of the Life of Dr. Noel Bartholomeusz’ edited by Prof. A.H. Sheriffdeen, doyen of surgery of our times and the Chief Guest today, together with Nirmali Hettiarachchi. This was a great help, and I am so thankful to both of them.

Born on 25 December 1910 as the son of an advocate of the Supreme Court during colonial times in Ceylon, a quiet and studious student Noel Bartholomeusz obtained LMS (Ceylon) in 1935 from Colombo Medical College topping the batch. Two other eminent surgeons, Dr. R.L. Spittel and Dr. L.D.C. Austin were in the same batch.

He married his theatre nurse Nora in 1936. The way he proposed to Nora was very interesting. At the end of an operation, he turned to Nora who was assisting him and said, “Nora, I have decided to get married.” So, she asked, “Who is going to be this unfortunate lady?” And that was it.

Soon after the World War II, he went to UK on a Government scholarship for postgraduate training. Within two years, he passed final FRCS. A.T.S. Paul, a senior cardiothoracic surgeon remembers Dr. Bartholomeusz telling him in a casual tone at the Viva of final FRCS in London when questioned about the technique of splenectomy that he had not encountered any problems with the number of cases he had personally operated in Ceylon. On return he was appointed a surgeon at the General Hospital, Colombo.

A handsome young man always wearing only white satin drill suits, white buckskin shoes, white socks and a coloured tie matching his white shirt with an orchid in his left buttonhole, he would have been an unmistakable figure in the hospital that had only few surgeons.

One of his intern medical officers, late Dr. Christopher Canagaretna, who later became the Professor of Surgery at North Colombo Medical College, writing about his chief, describes him as a very meticulous surgeon greatly respected by all for his dedication and expertise. He was a surgeon who never believed in advertising his skills, he says. He always said that the best advertisements were his patients.

His chief was very conscious of time. Dr. Bartholomeusz used to say that if you get late to theatre, you not only insult your anaesthetist and theatre staff but also your patient. He was very particular about his appearance and when he visited every morning sharp at 7 a.m. for the ward round, he had a different colour orchid flower in his buttonhole and story goes that it was Nora who would place this orchid each morning from their well-maintained orchid garden which we still maintain at the college premises. At the end of the ward round in the female ward, he would invariably look around and present this orchid to a patient.

Dr. Tony Gabriel, another giant surgeon of his era, was the assistant surgeon to Dr. Noel Bartholomeusz. I was fortunate to work with Dr. Gabriel as his assistant surgeon when I returned from UK. He describes Dr. Bartholomeusz as one of the guiding lights in his surgical career, a very nice man, very easy to get on with and with a very high standard of ethics. He writes, I quote, “I admired him not only for his techniques and ability as a surgeon but also because of the person he was and the standards he set.” Such a statement from Dr. Tony Gabriel I know speaks volumes of Dr. Noel Bartholomeusz.

After a premature retirement he continued a lucrative private practice in Colombo. Unfortunately, his life was shortened by his failing kidneys and was on dialysis machine at home every night under the loving care and moral support of his wife Nora. This did not deter him from his lifelong wish to serve his patients till the end, working up to three days prior to his peaceful death on 27 November 1977.

Nora and Noel were an affectionate couple for over 40 years in their lovely home. They were an extremely generous couple. His longstanding friend and his anaesthetist Dr. B.S. Perera had said that he was not at all surprised when he was informed by Prof. Sheriffdeen that this magnificent property has been gifted to the College of Surgeons of Sri Lanka by Noel and Nora. May their souls rest in peace.

Dr. Noel Bartholomeusz practiced the art and craft of surgery with only few surgeons during the colonial era, at a time when doctors were treated with utmost respect and kept in a high pedestal by the society. When a doctor makes a house call during these times, he would be offered a chair covered with a white cloth, a courtesy given to Buddhist monks and other religious dignitaries. This was an era in which patients perceived that doctors would always do the best for them, blindly accepting all complications related to surgical interventions as just inevitable. No questions were asked. This was the era of the autonomous clinician. This era is long gone. The modern medical care has now become a form of customer care. Customer perceptions are central to the quality of care as perceived by the customer.

As a result of the information explosion, rapid advances in communication technology and, knowledge about human rights, the modern society has developed high expectations of care outcomes. Poor outcomes arising from ignorance, inaptitude, and risk-taking behaviour, are no longer acceptable. Quality of care and the accountability have become key issues. Patient safety has been increasingly recognised as an issue of global importance.

Assuring quality in our undergraduate and postgraduate training programmes and professional approach in our day-to-day practice, is therefore of paramount importance today. This is especially important when working in high-risk environments like operation theatres.

Of course, operation theatres are not the only high-risk environments, and we are not the only professionals practicing in high-risk environments. Complexity engineering and complexity science are considered as complex or sometimes more complex than complexity medicine today.

We must therefore be mindful that, irrespective of the professions we practice, the assurance of quality in whatever we do is essential for good outcomes. This principle applies to all forms of higher education and training.

As someone who was also involved in policy formulation in the field of higher education in this country, I felt that I may use this opportunity to share with you some measures taken to ensure quality in the Sri Lankan higher education system and major challenges in this journey.

Basic structure of the higher education system in Sri Lanka

The structure of Sri Lanka’s higher education system comprises three major types of institutions: i. Universities and other Higher Education Institutes (HEIs) functioning under the Ministry of Higher education (MoHE) Sector of the Ministry of Education. Under the MoHE is the University Grants Commission (UGC) which oversees 18 State universities and 21 State HEIs around the country. There are two other State universities directly administered and managed by the MoHE and are not subject to UGC regulations: ii. Three universities functioning under ministries other than MoHE which provide higher education at institutions established directly under their supervision. For example, Kotelawela Defence University (KDU) operates under the Ministry of Defence: iii Private universities and other private HEIs which include three categories: a. local degree awarding institutes, 24 in number, which are established under the Companies Act No 17 of 1982; b. Cross-border institutes registered under the Companies Act. Many operate as local affiliates of foreign universities and offer foreign university programmes in Sri Lanka. Some students do part of the programme in a foreign country. At present there are 46 such institutes; c. Professional bodies/associations established under different Ordinances or Acts which have regulatory powers in professional higher education, that is, degrees leading to a practice of a specific profession. For example, the Engineering Council of Sri Lanka (ECSL), Sri Lanka Medical Council (SLMC), and the Council of Legal education to name a few. When a student is awarded a degree in a Professional degree programme, they should obtain a certificate from the relevant professional body to practice certifying their ‘fitness to practice’.

A glimpse of the evolution of free higher education in post-colonial Sri Lanka

Sri Lankans are blessed with two great historical decisions of our forefathers, free education and free health. Free education together with many incentives immensely benefited the people, especially the rural youth. Amply supported by the systems established by the British, there was a great socio-economic progress after independence. The data in late 1950s provide evidence. Economic indices of the country were second only to Japan. During this era, University of Ceylon was recognised as a great educational institution of Asia.

The free education policy provided equal opportunities for all to receive formal education that brought great benefits such as high literacy rates and other Human Development Indices (HDI) and Sri Lanka has been ranked in the high human development category in the global ranking and highest ranked country in South Asia in 2019. (Slide 11) UN Human Development Report 2020)

Free State higher education was a great asset. However, the full potential of its benefits could not be realised, in my view, due to several issues related to the assurance of quality and as a result of which the country lagged behind when compared with the progress of higher education in the regional countries. These issues are:

1. Underfunded higher education

When the demand for higher education grew with the increasing population, successive governments could not support the increasing demand with resource allocations in terms of % share of GDP and, this hindered the quality and standards of higher education. In other words, the equity of higher education was enhanced at the expense of quality.

It appeared that unfortunately, the value of higher education could not be sufficiently recognised when allocating resources in terms of the GDP over the years, in the face of the severe competition for resources such as free health care. This is evident when one considers the State investment for higher education as a percentage share of GDP. According to the most recent data available, at 0.3% GDP in 2015 and 0.4% in 2018, Sri Lanka’s public spending on higher education is one of the lowest in South Asia. (UNESCO Science Report 2015; 2020)

2. Free higher education as a right

The concept, ‘free State higher education’ is a great asset and a very noble concept indeed. However, what it means in practice is, anyone who gets three simple passes in Sri Lankan GCE Advanced Level (GCE/AL) examination would expect admission to a State university, free of cost.

Of course, no government should ever deny the right to higher education for students who qualify. Most countries addressed this challenge by implementing sustainable State-sponsored funding schemes (bursaries, loans) for students who just could not reach that level to qualify for a free university place, to pay back, after finding employment. The heavily State-subsidised Open University concept was such an extension. However, no sustainable strategy has ever been proposed and implemented to effectively address this issue.

3. Fee-paying higher education is nail in the coffin for free State higher education

An idea propagated by some, an easy sell to rural youth. Lack of English proficiency was an added stimulus to propagate this belief. This ‘subculture’ inhibited the synergistic relationship between the progress of public and private higher education in Sri Lanka and added further pressure on successive governments to adopt our higher education strategies to changing global and regional trends and, while regional countries progressed, Sri Lanka lagged behind.

4. Arrival of a new sub-culture – ‘Ragging’

The impact of a little-known fact to many. The arrival of a systematic brain washing method in all State universities, erroneously referred to as ‘university subculture’ which is in fact, is really, an inhumane form of harassment called ragging.

This culture was born around the times of southern youth uprisings and was passed from generation to generation by outbound training programmes organised by some student bodies, given to selected candidates after careful vetting to identify the ‘brain washable’ students. The impact on unsuspecting innocent bright rural youth who come in with minimum social skills and poor English language proficiency was immense.

They were also forced not to learn English, not to speak in English, not to visit libraries during this period of harassment which has extended in some universities to eight months from the day of admission, not to mention some inhuman experiences during this period like rituals to tame them, like what was witnessed during the times of slavery.

To address this, in 2015, the UGC created a Standing Committee on Gender Equity and Equality and in 2016, ‘Centre for Gender Equity and Equality, Sexual and Gender-based Violence and Ragging,’ with the objective of having a meaningful impact on this menace and also to provide a safe environment for students to lodge complaints because they were simply scared to complain within their own university.

In 2018, the UGC conducted a major study supported by UNICEF with investigators from UNICEF and universities. Eight universities were randomly selected. The study had a quantitative and qualitative arm. In-depth interviews with vice chancellors, deans of faculties, student councillors, student leaders, students, and academic and non-academic staff members were conducted. The data collection commenced in September 2018. The results amply highlighted the depth and the gravity of the problem.

A set of strategies and actions for combating ragging and SGBV were developed through this system-wide research and validated at consultative meetings with diverse stakeholders. Through this system -wide research, a new Circular on Strategies and Actions to be implemented to combat ragging and SGBV in State Universities and HEIs was released in 2019 and universities and institutes were directed to implement the strategies and actions given in the Commission Circular. As per the Universities Act No. 16 of 1978, as principal executive officers, the vice chancellors and directors are directly responsible for the maintenance of discipline within a university or Institute, not the UGC.

Another study conducted by the UGC with the 2017/2018 intake revealed that 1289 students who were registered in State universities in that academic year either did not come or prematurely left. The most common cause cited by them was ragging.

5. Lack of responsibility of State universities to address the skills mismatch

Skills mismatch is the mismatch between the set of skills and the attitudes expected by the employer and what the students acquire in our State higher education system. The data says it all.

In 2017, UGC undertook a UNESCO funded Tracer study titled ‘Graduate Employability survey’ to analyse the employment status of the graduates, two years after graduation.

Of 30,000 graduates from the 2014/2015 batch, 5,000 were selected using a stratified random sampling method. We analysed three main aspects in detail. We looked at the employability status by universities, the Employability status by the study stream and the Employability status by the results of GCE/ OL and GCE /AL General English.

The results were revealing. Due to time constraints, only two key findings are highlighted.

i. Employability status

The study revealed that, after studying in the university for five years, 50.3% of students who entered the ‘Humanities and Social Sciences stream’ that is, arts stream, were found unemployed two years after graduation. An additional 4.04 % were underemployed. This means that, nearly 54 % were still unemployed or underemployed, two years after graduation. The arts stream is the one that has the highest intake in Sri Lankan State universities today as opposed to a developed Asian country like Singapore which prioritises the economically relevant study streams in their intake.

ii. Impact of English

When the link between the English proficiency and employability prospects was analysed, it was revealed that those who had an A in General English at GCE/AL, irrespective of the degree programmes they entered, 88.3% were found employed at two years after graduation.

This this is the present status of skills mismatch in Sri Lanka. Even though successive governments and authorities have attempted to get the universities to address the issue, this study shows that this has not materialised.

In the opinion of the University Grants Commission then, the main reason for this is that the academic, administrative, and financial performance, Quality Assurance Grade, and accountability of State universities have never been seriously linked to State funding, academic promotions and salary increments of academics.

Why one has to be more accountable if it is not going to affect the salary and promotional prospects?

To address this issue, the UGC in 2019, submitted a comprehensive set of proposals to the Hon Prime Minister, requesting greater autonomy to State universities that includes financial autonomy, but coupled with a performance-based funding system to make university academia and administration, more independent and accountable.

As a short-term strategy to address the skills mismatch, the UGC and MoHE launched a $ 100 million World Bank Project, the biggest of its kind since independence, to encourage the universities to introduce new economically relevant degree programmes. To enhance the quality and accountability of university academics, after two years of extensive discussion by an expert committee with academic union representatives, a new promotion Circular was released by the UGC in 2019.

All the above issues have an impact on the quality of higher education. Therefore, I will very briefly explain why quality is needed and how it is assured in the field of higher education.

(To be continued)

The Noel and Nora Bartholomeusz Foundation