Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Friday, 30 October 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Rohan Samarajiva

A legitimate Constitution cannot be drafted under opaque conditions in a backroom and approved with  the votes of the party in power (and those of a few crossovers). All but the 17th and 19th Amendments to the 1978 Constitution lacked legitimacy for this reason.

the votes of the party in power (and those of a few crossovers). All but the 17th and 19th Amendments to the 1978 Constitution lacked legitimacy for this reason.

How Constitutions are Made

There are those who point to the way the US Constitution (the shortest, oldest, and possibly least amended) and the Indian Constitution (the longest and possibly the most amended) were drafted and adopted. The drafting and the adoption of the US Constitution took over a year of dedicated work. The Indian Constitution took almost three years. Persons not members of the then existing legislatures were among those responsible for the drafting. Both were adopted in the aftermath of a successful struggle for independence. Those modes have limited relevance for Sri Lanka in 2020.

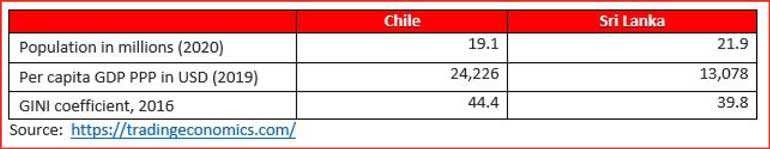

Chile may have some lessons. Chile and Sri Lanka (and China a little later) were the first to dismantle state controls hobbling their economies. Chile’s Constitution was adopted in 1980 under Augusto Pinochet, ours in 1978 under J.R. Jayewardene. Chile became the richest country in Latin America under the 1980 Constitution, which later governments amended dozens of times.

Since 1990 the economy has grown rapidly, poverty has fallen sharply, and politics have been stable with several peaceful changes of power. Despite significant recent decline from one of the world’s highest levels of inequality as measured by a GINI (where high is bad) of 56 in 1995, Chile is still more unequal than Sri Lanka, which has the highest inequality in South Asia, excluding the Maldives.

There is great unhappiness about the Constitution in Chile, expressed in the streets last year. For example, when efforts were made to strengthen the consumer-protection agency, by allowing it to impose fines on companies, the Constitutional Tribunal overruled it. Changes to laws on education, policing, mining, and elections require four-sevenths majorities in both houses of Congress. It is a “hyperpresidential” Constitution, which gives the president the power to dictate which bills get priority in Congress. Members may not propose tax or spending bills. Regions cannot raise their own revenues, which concentrates power in the center.

On October 25th voters went to a referendum to decide on whether drafting the new Constitution should be done by an elected assembly, half of whose members would be women, or by a convention split evenly between elected delegates and members of the legislature. The drafting assembly is to be elected in April 2021.

Sri Lankan Practice

In 2015, the Sri Lankan Parliament formed itself into a Constitutional Assembly. The channel for ideas from those outside the legislature was a Committee on Public Representations headed by Lal Wijenayake, a respected lawyer independent of the two main parties then in power.

What was promised in the 2019 Saubhagyaye Dakma was: “A Parliamentary Select Committee will be appointed to engage with the people, political leaders, and civil society groups and prepare a new constitution for Sri Lanka.” This is yet to be done. What has been appointed is a committee of nine lawyers, mostly supporters of the President. Another member is to be appointed to represent the Tamils of Indian Origin.

A bunch of appointed lawyers headed by the man who headed the President’s stonewalling of the legal process prior to his election is completely unacceptable. A select committee will at least allow the participation of parties outside the government who will get to decide who their representatives are.

Principal-Agent Theory

It is said that war is too important to be left to the Generals. In the same way, Constitutions are too important to be left to the lawyers (as proposed), or to the politicians (as has been mostly the case in Sri Lanka).

A Constitution sets out “the rules of the game,” by which the people’s agents must act. The people are the Principal. The individuals who won the last Presidential and Parliamentary elections are their Agents. They are supposed to act on behalf of the People, but they have their own agendas and priorities. And they have an informational advantage over the people. They engage in politics full time, while the people have to work to keep themselves and their agents clothed and fed.

It would be illogical for the Agents to unilaterally define the “rules of the game.” The Principal, the people who are not professional politicians, must play a determining role. In an ideal world, a Constitution would be made from the bottom up, extracting the rules of governance from the lived experience of the people. But this is unrealistic.

As established in 1965 by Mancur Olson in his seminal book, The logic of collective action, in public affairs small groups with concentrated interests tend to overwhelm large groups with diffuse interests. Politicians, moneyed interests, and even some intellectuals with independent livelihoods can focus their time and resources on specific issues, such as Constitution making. Members of the public must earn a living, care for their children and parents, and do myriad other things. They lack the ability to match the focus of those with concentrated interests. They also think that someone will look after their interests, leading to the “free-rider problem.”

Pragmatic Solutions

The 2015 solution of a dedicated committee mandated to seek and organize public representations could be taken as a starting point. The documentation that was compiled is available for examination by all. Additional material can be solicited using the affordances of the Internet, and not just through newspaper advertisements seeking written submissions addressing pre-defined subject areas. Debates can be organized on late-night TV to seed the process. But most importantly, the key decisions must be based on consensus and compromise. In Chile, all decisions of the Constitutional Assembly require a two thirds majority. Because Constitutions are not made to steamroller minorities into submission, it is necessary to ensure that all kinds of constituencies are represented in the Assembly and that those controlling the government do not dominate proceedings.

Because all our elections descend into partisan contests, it may not be advisable to hold elections as the Chileans plan to do. Perhaps some kinds of quotas can be agreed upon for political parties, civil society, professional associations and so on with special cross-cutting quotas being enforced to ensure representation of women and persons with disabilities.

The whole process should be overseen by a respected individual or individuals who forswear political activity for the next five years. As in Chile, half the seats in the assembly should be reserved for persons not engaged in active electoral politics. The government can assure itself of final control because the half appointed from among legislators will be mostly their representatives. These rules should, as in Chile, be approved by a referendum. As with all referenda, the most difficult challenge is the framing of the questions.