Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Saturday, 23 December 2017 00:55 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

If I were at the Beijing Forum on Human Rights the other day (7 and 8 December), I would have proposed the following sentence, after the first two sentences in Article 1 of the Beijing Declaration on human rights:

If I were at the Beijing Forum on Human Rights the other day (7 and 8 December), I would have proposed the following sentence, after the first two sentences in Article 1 of the Beijing Declaration on human rights:

“This however should not be taken as an excuse to deny or delay the human rights implementation in respective countries.”

The first two sentences are the following:

“In order to ensure universal acceptance and observance of human rights, the realisation of human rights must take into account regional and national contexts, and political, economic, social, cultural, historical and religious backgrounds. The cause of human rights must and can only be advanced in accordance with the national conditions and the needs of the peoples.”

The ‘national conditions’ and the ‘needs of the people’ (however you define), are two valid points that the Declaration has brought into consideration that most often the Western countries and the UN organisations neglect in their heavily legalistic or political approaches to human rights.

However, there is another danger that a common human rights declaration has to avoid, particularly coming from our own Afro-Asian and Latin American countries. That is the misuse of these two propositions in order to deny, delay or circumvent the acceptance and implementation of human rights that the Declaration has identified in the subsequent articles.

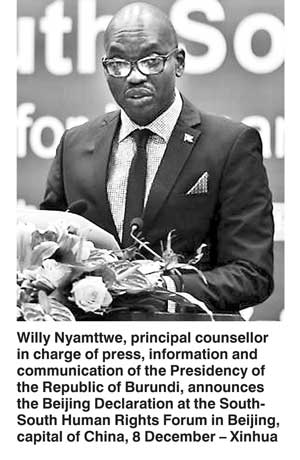

Reportedly, 70 mainly developing countries and international organisations have participated at this First South-South Human Rights Forum, 300 delegates taking active part in the discussions. China has been the convenor of the Forum (Xinhua, 8 December).

Justification

The Declaration is unique in that it has brought to the forefront the ‘particularities’ that the developing countries are facing in the implementation of human rights, that the Chinese President, Xi Jinping, himself has emphasised in his message to the Forum. That is justified. Because there is no much point in repeating again and again what the Universal Declaration (1948) or other similar declarations have pronounced, like in the Vienna Declaration (1993) or previously the Tehran Declaration (1963).

Even in Sri Lanka what has been typical of many human rights advocates or academics is that they repeat again and again the accepted notions of human rights like reciting a ‘religious sermon or prayer.’ There is no critical thinking on how to promote, ensure and implement human rights. Perhaps their mistake originates within the notions of ‘legality’ that they try to implement without any consideration for economic and social conditions of developing countries.

Of course at a personal level of violations, the perpetrators should be brought before the law. But the problems are related to recurrence of human rights issues in developing countries at a societal level where solutions cannot easily be found. As a result, at times, measures taken to allegedly ameliorate human rights themselves can exacerbate the situations.

There are instances where human rights advocacy, particularly from international agencies, create further conflicts and leads to further human rights violations. While there are so many experts on the subject of human rights, there have been no known effort since 1948 to investigate why human rights violations occur in societies and what are the salient social and economic conditions. There are no international ‘declarations’ on the subject. Often, only political and legal factors are identified, and countries are pressured in a partial manner to implement them.

Therefore in the above context, the Beijing Declaration can be considered an important effort trying its best to strike a balance between ‘universality’ and particular social, economic and historical conditions of developing countries.

Universalitys

The Declaration is not against ‘universality’. But as it begins, ‘in order to ensure universal acceptance and observance of human rights,’ it focuses more on practicalities than one-sided pronouncements, saying that:

“States and the international community have a responsibility to create the necessary conditions for the realisation of human rights, including the maintenance of peace, security and stability, the promotion of economic and social development and the removal of obstacles to the realisation of human rights.” (From Article 1.)

It is not so much on the basic UN declarations or the international covenants that the disagreements exist within the actual ‘international community,’ but in the way that these principles are applied or propagated.

Therefore in that context, the call for the recognition of ‘civilisational equality’ should be considered a necessary and an integral part of ‘universality.’ It is difficult to accept that the universality should be based on the norms and beliefs of one civilisation or a single belief system. The relevant proclamation of the Declaration is as follows:

“Human rights are an integral part of all civilisations, and all civilisations should be recognised as equal and should be respected. Values and ethics of different cultural backgrounds should be cherished and respected, and mutual tolerance, exchange and reference should be honoured.” (From Article 2.)

It is not a ‘clash of civilisations’ that is advocated here, but harmony and mutual respect of all civilisations.

Further on the questions of universality, the Beijing Declaration is based on the Universal Declaration (UDHR) of 1948, but one can easily notice that it goes beyond as follows.

“All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. Human dignity is not only related to human freedom, but also decisive to the all-round development of human beings. Human rights are the unity of individual rights and collective rights.” (From Article 4.)

The first sentence is obviously from the Universal Declaration, but the second and the third are different. What it says is that ‘human dignity does not relate only to human freedom.’ A concept of ‘all-round development of human beings’ is advocated, although not elaborated. Also important is to highlight a ‘new’ interpretation of human rights as the ‘unity of individual rights and collective rights.’ This goes beyond the current acceptance of ‘collective rights’ parallel to ‘individual rights.’

The Beijing Declaration does not in any way negate the Universal Declaration. It is an enhancement based more or less on the same universal principles and endorses and promotes the international compliance in the following manner.

“Human rights are inalienable, and all countries should make efforts to promote the legal guarantee of human rights.” (From Article 5.)

“States should, in accordance with their national laws and international obligations, focus on guaranteeing the human rights and fundamental freedoms…” (From Article 6.)

Another lacunae

Another lacunae

(women’s rights?)

There is however another lacunae or oversight. In Article 6, group rights are emphasised in the following manner.

“States should, in accordance with their national laws and international obligations, focus on guaranteeing the human rights and fundamental freedoms of specific groups, including ethnic, national, racial, religious and linguistic groups and migrant workers, people with disabilities, indigenous people, refugees and displaced persons.”

What is missing here are the rights of women and also children. It may be argued that women or children are not specific groups in society like ethnic, racial or religious groups. But that is not logical or rational. Given the biological as well as social conditions, women are the most vulnerable ‘specific group’ in society. In fact in 1995, there was another Beijing Declaration on Women’s Rights. However, nowhere in the present Declaration the rights of women or children are mentioned.

Right to development

A major thrust of the Declaration can be considered on the ‘right to development’ and ‘economic, social and cultural rights.’ Article 3 particularly is devoted to the right to development. The Declaration’s initial pronouncements on the ‘regional and national contexts, and political, economic, social, cultural and historical backgrounds’ make perfect sense with this article.

In 1980s, leading to the UN Declaration on the Right to Development (1986) and immediately thereafter, there was much recognition of this right of the world’s poor and the poor countries. But then with the demise of the Soviet Union and the advent of neo-liberalism, the whole emphasis became turned upside down. There were many experts arguing that the ‘right to development’ is not a human right. Therefore in that context, the emphasis on the right to development in the Beijing Declaration can be considered an important milestone, and rather a ‘turn of tables.’

Article 3 begins with saying that “The right to subsistence and the right to development are the primary basic human rights.” Then it interprets the meaning of that right in the following manner.

“The main body of the right to development is the people. In order to maximise the overall interests of mankind, it is necessary to uphold the unity of the right to development at individual level and the right to development at collective level, so that all peoples have equal opportunities for development and fully realise the right to development.”

It is important that the Declaration synergises the right to development at the individual as well as the collective level. More importantly, it motivates the developing countries to pay attention to, in my words, the ‘rights of the poor,’ in upholding the overall right to development. This is equally valid in the case of some ‘developed’ countries as well.

“Developing countries should pay special attention to safeguarding the people’s right to subsistence and right to development, especially to achieve a decent standard of living, adequate food, clothing, and clean drinking water, the right to housing, the right to security, work, education, and the right to health and social security.”

Then it emphasises the ‘responsibilities’ of the international community and the countries concerned in upholding and ensuring the right to development of the people in the following manner.

“The international community should take the eradication of poverty and hunger as the primary task, and strive to solve the problem of insufficient and unsustainable development and create more favourable conditions for the realisation of the people’s right to development especially in the developing countries.”

Rights and responsibilities

Indivisibility and interdependence of human rights in the Declaration are emphasised in two main ways. First is in the sphere of civil and political rights on the one hand, and the economic, social and cultural rights on the other.

The most important proposition in this regard is the following: “The acquisition of civil and political rights is inseparable from the simultaneous acquisition of economic, social and cultural rights, which are equally important and interrelated.” (From Article 4.)

Second is in the sphere of rights and responsibilities. Although not elaborated, the following is sufficiently comprehensive in clearly emphasising the matter which is much neglected in many international discourses.

“Everyone is responsible to all others and to society, and the enjoyment of human rights and fundamental freedoms must be balanced with the fulfilment of corresponding responsibilities.” (From Article 5.)

Rejection of Interference

Rejection of Interference

The Declaration ends, one may say, with a political determination. It can also be considered a political punch. To be brief, it says:

“The politicisation, selectivity and double standards on the issue of human rights and the abuse of military, economic or other means to interfere in other countries’ affairs run counter to the purpose and spirit of human rights.” (From Article 8.)

The last sentence is much sober and can be considered an international appeal to the whole of the international community, saying:

“The international community should promote human rights cooperation through dialogue and exchange, mutual learning and mutual understanding and consensus-building on the basis of equality and mutual respect.” (From Article 9.)

Conclusion

The Beijing Declaration can be considered an important milestone in the evolution of human rights understanding and more particularly their practical implementation. Although it was declared in Beijing, it is not a Chinese declaration, although their initiative and thinking undoubtedly must have influenced its outcome. It is only nine lucidly-written articles which can easily be translated into Sinhala and Tamil. One may agree, disagree or somewhat agree with the whole or parts of the Declaration. As I have pointed out there are strong points, weaknesses and oversights in the Declaration. However, there is much food for thought. For example, although I have not discussed previously, it says, “In terms of human rights protection, there is no best way, only the better one.” Think about it. It also says, “The satisfaction of the people is the ultimate criterion to test the rationality of human rights and the way to guarantee them.” This is also food for thought.

My best takeaway from the Beijing Declaration is the following, what I would like to call ‘the rights of the poor.’ What are they? In essence they are: (1) a decent standard of living (2) adequate food and clothing (3) clean drinking water (4) decent housing (5) personal security at home and in society (6) the right to work (7) the right to education (8) to health and (9) the right to social security. Whatever we do to develop the country or the economy, the primary objective should be on these ‘rights of the poor’ and of course of all others.

(The full text of the Beijing Declaration can be accessed through China Daily, 8 December 2017. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201712/08/WS5a2aaa68a310eefe3e99ef85.html.)