Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Thursday, 1 August 2024 01:11 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

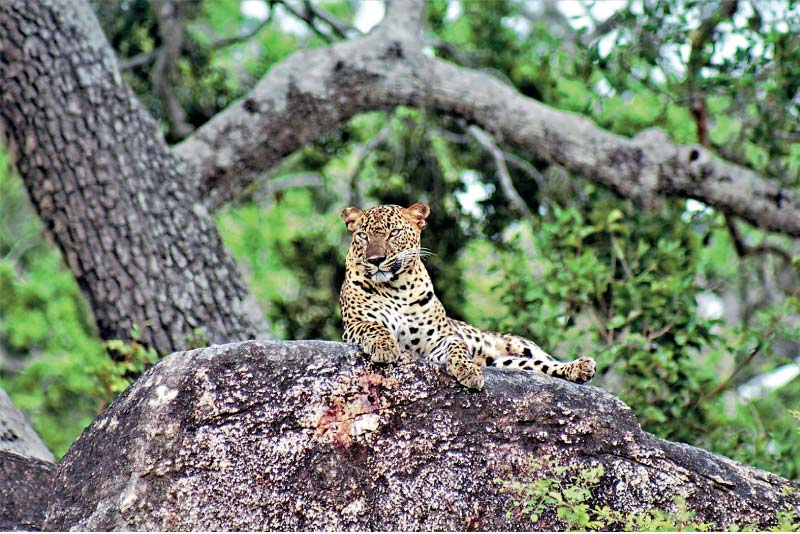

The Sri Lankan leopard – ‘panther pardus kotiya’ – Pic by Srilal Miththapala

Of all the charismatic animals seen in Sri Lanka, there is none that has created so much interest and popularity, than the Sri Lankan leopard. And today it has become arguably one of the most sought-after tourist attractions in the country. But is the leopard’s own popularity leading to its own destruction?

Of all the charismatic animals seen in Sri Lanka, there is none that has created so much interest and popularity, than the Sri Lankan leopard. And today it has become arguably one of the most sought-after tourist attractions in the country. But is the leopard’s own popularity leading to its own destruction?

1 August is Sri Lanka Leopard Day, a day proposed by the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka in 2020 to celebrate our very own leopard sub species.

So this maybe an overtime moment to reflect on the problems that the Sri Lanka leopard is facing today.

Introduction

The Sri Lankan leopard is a distinct subspecies – ‘panthera pardus kotiya’ (after Dr. Sriyanie Miththapala 1966). It is the only large carnivore found in Sri Lanka, and is therefore the apex predator in the wild, with no threats to it other than man.

It has been listed as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List, with only an estimated population less than 800 mature individuals, which is probably declining. (Kittle, A.M. & Watson, A. 2020). The leopard is still found in all habitats throughout the island in both protected and unprotected areas, including the central highlands. However they are mostly nocturnal and wary of humans and are therefore quite difficult to spot.

However a growing population in a relatively small area of block 1 (141 sq. km) in the Yala National Park (NP) started the current leopard-centric tourism interest. With more visitors it was inevitable that these leopards got habituated to humans (in safari jeeps). Today, the spotting of a leopard in Yala NP block 1 is almost guaranteed, fuelling large visitor inflows to the park.

With increased visitation and poor enforcement of park rules and regulations, over crowing and over-visitation at Yala NP has spiralled out of control. (Over visitation is where the number tourists occupying a particular destination or area exceeds its intended or optimal capacity. Over-crowding is when a large number of visitors coverage on one single attraction at a given time).

In 2018 (the best ever year for tourism in Sri Lanka) almost half of all tourists arriving in the country visited a wildlife park. In that year 311,878 tourists visited Yala which accounts to about one-third of the above number visiting the national parks. (SLTDA, 2018).

Today the leopards in Yala NP are being hounded out, disrupting their natural movement and lifestyle, causing stress to the leopards, which in turn results in other serous conditions. “Overexposure to stress can cause physiological problems, such as weight loss, changes to the immune system and decreased reproductive capacity” (Chronic Stress on Wild Animals National Library of Medicine 2019).

So what should be the response of the tourism industry (who is partly to blame for this impending debacle) to mitigate this problem?

Possible mitigation activities by the tourism industry

Possible mitigation activities by the tourism industry

Conclusion

Conclusion

It therefore quite evident that there are a number of possible solutions to this problem. It is true that there is no ‘one-quick-fix’, but all of the above will in some way help mitigate the prevailing undesirable situation. Of course at the end of the day most of the responsibility for this situation rests fairly and squarely on the Department of Wildlife Conservation, but it will be a ‘pipe dream’ to expect that they will be able to ‘put their house in order’.

Therefore it is imperative that all tourism stakeholders put their ‘shoulders to the wheel’ to help mitigate the ongoing problems.

For after all, the wildlife viewing experience is one Sri Lanka tourism’s Golden Geese, and they should not allow the Golden Eggs be taken away from them!