Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Wednesday, 6 December 2023 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The Avukana incident, in its absurd nature and atrocious aftermath, is symptomatic of the danger this degenerated faith and its ambitious adherents pose

“So it goes.” Kurt Vonnegut (Slaughterhouse-Five)

By Tisaranee Gunasekara

By Tisaranee Gunasekara

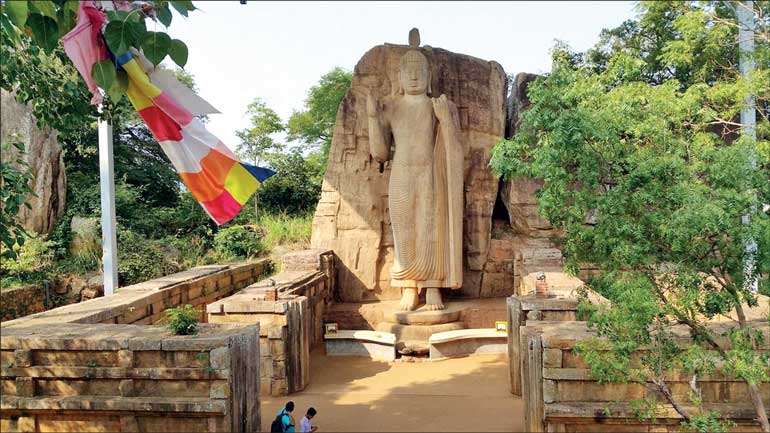

In the grand scheme of things, a monk and a quack draping a robe on a Buddha statue may seem silly, at most. Even if the statue is a 1,500-year-old work of art. Sri Lanka, contrary to President Wickremesinghe’s assertions, is still teetering on the rotten-bridge, a bankrupt country with fractious leaders and no good options. What does one act of vandalism matter?

What is significant is what didn’t happen.

According to the law, the quack who masterminded the robe-draping at Avukana and the monk who permitted it should have been arrested and charged. There’s no dearth of evidence, videos, pictures, words of perpetrators themselves. Yet, police are moving at glacial pace. The chances of the perpetrators getting away scot-free are considerable as the march of time sweeps away the memory of their crime.

In Sri Lanka, saffron is the new colour of impunity. There’s very little a man cannot get away with, from slapstick comic to violently dangerous, if he happens to wear a yellow robe. Monks are not just above the law; they have a law unto themselves. Often, they are the law.

Dr. Gabo Maté, a Holocaust survivor, recently highlighted the double-standards in the Western coverage of the Palestinian issue. “…when demonstrators throw stones at the police in Hong Kong, that is considered to be heroism in American press. When Palestinian kids throw stones at the Israeli soldiers they are called terrorists” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z0P67aWO1V0). Lankan media accord an identical impunity to monks who break laws and norms. Pastor Jerome Fernando is lambasted for stating his belief in the greatness of Christ – would he be a Christian otherwise? – while Pitiduwe Siridhamma thero’s (aka Arhat Sammanthabadra) distorting of Tripitaka is mostly ignored. One is arrested. The other gets away with an apology.

Zeid Al Hussein, the former UN Human Rights Commissioner, introduced the phrase, tribalism of pain to explain official Western indifference to Gazan sufferings. In Sri Lanka, we have tribalism of law. If you are a monk or a lay Sinhala-Buddhist extremist, the uniformed guardians of law permit you immeasurable leeway. You can invade State institutions, vandalise archaeological monuments, threaten and attack people, and still remain freer than birds.

The impunity goes beyond legal. Politicians who yell at everything ignored the crime committed at the Avukana statue. Monks who interfere in everything turned a collective blind eye to this outrage against Buddhist teachings and traditions. Society, at large, seemed unconcerned. Had the Archaeological Department not intervened, however belatedly, Aukana robe-draping might have kicked off a new trend. Dressing Buddha statues with robes, as if they were mannequins in a shop window, and providing them with slippers – and other such essentials – could have become the new normal.

The impunity goes beyond legal. Politicians who yell at everything ignored the crime committed at the Avukana statue. Monks who interfere in everything turned a collective blind eye to this outrage against Buddhist teachings and traditions. Society, at large, seemed unconcerned. Had the Archaeological Department not intervened, however belatedly, Aukana robe-draping might have kicked off a new trend. Dressing Buddha statues with robes, as if they were mannequins in a shop window, and providing them with slippers – and other such essentials – could have become the new normal.

The Avukana incident is a mirror reflecting the times we live in and an omen of the future that maybe ours. Irrational is the new rational. Gullibility is the highest virtue. We are all unthinking believers now, unquestioning followers, of something or someone. The mind-set that gave us Gotabaya Rajapaksa and the Kelani Cobra lives and thrives.

Superstition is a political thing. In addling minds, in inculcating habits of non-thinking, it enables political outcomes of the worst sort. To paraphrase a quote attributed to Voltaire, belief in absurdities can result in acts of atrocious stupidities of the boomeranging kind. Despairing times are ideal for such inanities. 2024 can be another 2019.

In 2022, Ranil Wickremesinghe gained some political capital by ending deadly queues and resorting a kind of normalcy. In 2023, he exhausted that capital by embroiling himself in disasters, the appointment of Deshabandu Tennakoan as the acting IGP being the latest case in point. Economically, we are back to spending money we don’t have and filling the gap by taxing the poor. According to the latest UNDP report, 55.7% of the population are multi-dimensionally vulnerable. This distress will worsen in 2024, when new VAT hikes kick in.

European economic recovery, post-WWI penalised the poor. The end result was violent political instability and a new war. Post-WWII, Europe opted for a more just economic path, imposing greater burdens on the rich via stratospherically high direct taxes and channelling that money into a multi-faceted welfare state. That led to decades of peace and prosperity.

Recovery is necessary. But much depends on the kind of recovery. Growth rates matter naught, if benefits are gobbled by the rich. Declining inflation is immaterial if ordinary masses have to spend more on daily essentials. When living is a chore, blasé chatter about how well things are going can grate to the point of madness. 2024 promises to be a year like that.

Unsettling settlements

In 2013, Sinhala Ravaya, under Rajapaksa patronage, ‘resettled’ several Sinhala-Buddhist families in Navakkuli, Jaffna, built a temple for them, and named it Sihalaramaya (temple of the Sinhalese). Dinasena Ratugamage writing in Irida Divaina called the exercise ‘inane piety which creates religious wars’.

Sihalaramaya was one of many temples set up in the North and the East during the Rajapaksa years. Since there were no civilian Buddhists in those areas, the military became the sole builder and dayakya (donator/sustainer). This strengthened the nexus between Sinhala-Buddhist monks and Sinhala-Buddhist military, a visceral bond impeding the necessary creation of a Lankan nation undergirded by a Lankan military and a non-Sinhala-Buddhism.

Populists, says political philosopher Jan-Werner Müller, believe they are the sole representative of ‘the real people’ and the silent majority.’ In a Lankan context this is always a euphemism for Sinhalese and especially Sinhala-Buddhists. From 2005 to 2022, the Rajapaksas were the incontestable sole representatives of Lanka’s real people. Now the position is vacant. Had economic recovery continued to move in a more just direction, the space for populism would have diminished. As the gap between haves and have-nots grow, parallel to the number of have-nots, the room for populism cannot but expand. For any Sinhala-Buddhist with political ambitions (laypeople or monks) the temptation would be considerable.

To their credit, UNP, SLFP, SJB, and JVP are not trying to occupy this space overtly. They may not be anti-racist, but they do not peddle racism either. In this admirable reticence, political monks – and marginalised Sinhala parties and politicians – see an opportunity. In their eyes, racism is not a no-go area, but unclaimed ground waiting for its right claimant.

To their credit, UNP, SLFP, SJB, and JVP are not trying to occupy this space overtly. They may not be anti-racist, but they do not peddle racism either. In this admirable reticence, political monks – and marginalised Sinhala parties and politicians – see an opportunity. In their eyes, racism is not a no-go area, but unclaimed ground waiting for its right claimant.

So the Sihalaramaya syndrome is back, the project of claiming North and East for Sinhala-Buddhism, thereby completing the unfinished business of making Sri Lanka a Sinhala-Buddhist country. East is the main battleground, Divulapathana a possible flashpoint. In the absence of any public interest, the issue is being kept alive by activists and media. The latest entrant to the drama is Medagoda Abeytissa thero (who in 2020, called a vote for the Rajapaksas a merit to remember on deathbed). “No one understands Sinhala pain in the North-East,” he lamented. “Muslims and Tamils are allowed in while Sinhalese are not. Sinhalese have become refugees in their birthland.” Then came the threat. “If politicians won’t attend to this, we will ask the Mahanayaka theros to issue a sangha decree. We will gather the people and go as far as we can to regain the rights of Sinhala people in this country.”

As far as we can – how far would that be? When Sinhalese are gathered by monks to regain the rights of Sinhalese (taken from them by Tamils and Muslims), can that journey end in any other destination but violence?

In their project of demographic reengineering in the North and East, the Rajapaksas were influenced and inspired by the settlement policy of the Israeli right. Daniela Weiss is an extremist leader of this settler movement in the West Bank. In a recent interview, she set out in plain language, where this project is headed. “The borders of the homeland of the Jews are the Euphrates in the East and the Nile in the Southwest… We, the Jews, are the sovereigns in the state of Israel and the Land of Israel. They have to accept that… In Israel, there’s a lot of support for settlements, and this is why there have been right wing governments for so many years… we want to close the options for a Palestinian state and the world wants to leave the option open. It’s very simple thing to understand” (New Yorker – 11.11.2023).

Equally simple and comprehensible is the connection between this supremacist attitude and Israel’s inability to achieve peace not just for Palestinians but for itself. A political agenda driven by settlement mentality has brought nothing but war and devastation to Palestinians, Israelis, and the entire region. As Israeli politician and peace activist Avraham Burg wrote, this mindset of exclusivity and exclusionism has created a language of “tension and traumas, conflicts and confrontation” obliterating the possibility of a different language of “building bridges, understanding, forgiveness, and concessions” (The Holocaust is over. We must rise from its ashes). That linguistic choice closes door to reconciliation and peace, turning conflict into permanent national condition. This is one of the futures ahead of us, if the extremist monks and their lay allies have their way.

An unprecedented election

The coming election year also happens to be the 15th anniversary of the ending of the Eelam War. That fact will play a significant part in the politics and propaganda of the Rajapaksas and the political monks. The references will be celebratory and cautionary, glorying in the victory, while warning that the gains are being rolled back and must be recouped.

For decades, the UNP/anti-UNP divide dominated Lankan elections. Then it shifted to the Rajapaksa/anti-Rajapaksa divide. Now both markers are gone. The UNP is a spent force; the Rajapaksas are a pale shadow of what they once were. In that context, there are no simple demarcating lines, no either-or contestations.

The main battle will not fall between the Government and the opposition as it has always been. It will be drawn in the oppositional space, between its two main constituents, the SJB and the JVP. According to recent opinion polls, the JVP has pulled ahead, quite significantly. Though much can happen between now and election time, a Ranil Wickremesinghe recovery is highly unlikely and the two elections will pit SJB against JVP and Sajith Premadasa against Anura Kumara Dissanayake. Whatever the outcomes, the gap between the victor and the vanquished is unlikely to be wide. In such a situation, accusations of electoral malpractices will fly, and the loser may even try to occupy the streets to deny the (false) winner a chance to govern. Elections will bring legitimacy, not necessarily stability.

The main battle will not fall between the Government and the opposition as it has always been. It will be drawn in the oppositional space, between its two main constituents, the SJB and the JVP. According to recent opinion polls, the JVP has pulled ahead, quite significantly. Though much can happen between now and election time, a Ranil Wickremesinghe recovery is highly unlikely and the two elections will pit SJB against JVP and Sajith Premadasa against Anura Kumara Dissanayake. Whatever the outcomes, the gap between the victor and the vanquished is unlikely to be wide. In such a situation, accusations of electoral malpractices will fly, and the loser may even try to occupy the streets to deny the (false) winner a chance to govern. Elections will bring legitimacy, not necessarily stability.

While neither the JVP nor the SJB peddle racism in its raw form, both parties are putting considerable efforts to win over the main bulwarks of Sinhala-Buddhist majoritarianism. The JVP is aiming mainly at the military while the SJB is focusing on monks. As a result, neither party is willing to take on majoritarian supremacism or to offer minorities anything other than a pittance (SJB will give more than the JVP). Even more pertinently, given the economic mire we are sunk in, neither party would be willing to take on the financial elephant in the room – the gargantuan sums we persist in bestowing on the military, more than 14 years after the war ended. Without touching that massive pile, a just recovery is impossible. (Incidentally, a key purpose in trying to ignite an ethnic or religious clash is to render any actual reduction of military expenditure impossible).

Citizenship is an escape from clan identity, Brook Manville and Josiah Ober claim in The Civic Bargain. When clan identity seeps into citizenship, citizenship dies in all but name. In such places, you are a citizen only nominally; your real identity is tribal. And tribalism fits in well in any century including the 21st. It is universal in its sweep, timeless in its scope, and Sri Lanka in 2020s in no exception to this rule. One can hear it clearly when monks accuse Ranil Wickremesinghe of pandering to Tamils for their votes, whenever he promises to offer a political solution to the ethnic problem (a promise that is never kept). While pandering to Sinhala-Buddhists for their votes is kosher, any concession, even a verbal one, to minorities is decried as unfair and unjust. Since minorities too are Lankan citizens, what is wrong in cultivating their votes? The question is never asked, or seen as valid.

Irrespective who wins the upcoming elections, political monks and Sinhala-Buddhist supremacism will not lose, since the winning party will not oppose them and the losing party – in its chagrin – might kowtow to them. This political opportunism coupled with the impunity enjoyed by monks could render any meaningful financial, social or political reform – let alone a  political solution to the ethnic problem – impossible. As the winner falters and the loser ratchets up the tempo, monks, wielding the banner of a distorted Buddhism, will try to step into the breach, offering themselves as salvation. A kind of Sinhala-Buddhist clericalism will gradually become normal, pushing conflictual agendas and superstitious ideas. The Avukana incident, in its absurd nature and atrocious aftermath, is symptomatic of the danger this degenerated faith and its ambitious adherents pose.

political solution to the ethnic problem – impossible. As the winner falters and the loser ratchets up the tempo, monks, wielding the banner of a distorted Buddhism, will try to step into the breach, offering themselves as salvation. A kind of Sinhala-Buddhist clericalism will gradually become normal, pushing conflictual agendas and superstitious ideas. The Avukana incident, in its absurd nature and atrocious aftermath, is symptomatic of the danger this degenerated faith and its ambitious adherents pose.