Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Saturday, 28 October 2023 00:35 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

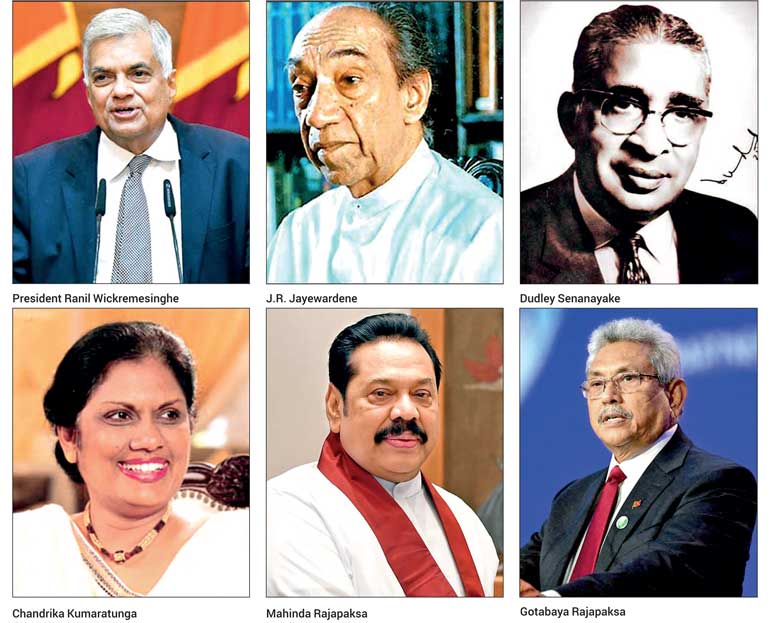

The message of the 2022 “Aragalaya”, which drove a President and a Prime Minister and other members of that political family out of office, expressed in clear and explicit terms, was a complete rejection of the authoritarian, patronage-based, corrupt system of governance introduced into this country by the 1978 Constitution and its 21 Amendments. 45 years of autocratic presidential rule marked by massive loss of human life and unprecedented levels of corruption, have demonstrated the need to restore the system of government that this country enjoyed for 25, if not 30, years since 1947.

The message of the 2022 “Aragalaya”, which drove a President and a Prime Minister and other members of that political family out of office, expressed in clear and explicit terms, was a complete rejection of the authoritarian, patronage-based, corrupt system of governance introduced into this country by the 1978 Constitution and its 21 Amendments. 45 years of autocratic presidential rule marked by massive loss of human life and unprecedented levels of corruption, have demonstrated the need to restore the system of government that this country enjoyed for 25, if not 30, years since 1947.

The parliamentary executive system

I am old enough to have lived through all three post-Independence Constitutions of this country, and especially the first. In my view, the 1946 Constitution served the country and its peoples best. If the purpose of a national constitution is to establish the essential framework of government by creating the principal institutions and defining their powers, that was precisely what it did. Drafted by one trained legal draftsman, based on the report of the Soulbury Commission and related documents, and endorsed by the four major communities represented in the State Council, that Constitution served us for 25 years without any significant amendments. Expressed in only 92 sections, it was, in my opinion, the model constitution. If it failed in some respects, it was due to the absence of a Bill of Rights.

Under that parliamentary executive system of government, the Head of State, who was also Head of the Executive, and Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, acted on the advice of the Prime Minister, while the Cabinet of Ministers headed by the Prime Minister and drawn from Parliament was charged with the direction and control of the Government and was collectively responsible to Parliament. That system facilitated regular democratic elections and periodic changes of government which enabled both right-wing and centrist or left-of-centre political parties to implement their respective economic and social policies without any hindrance.

The parliamentary executive system of governance it provided was flexible enough to deal effectively and expeditiously with the sudden death of the Prime Minister in 1951, an island-wide Hartal in 1953, the assassination of the Prime Minister in 1959, the attempted military Coup d’état in 1962, and the bloody JVP Insurgency in 1971. The independence of the Judiciary was protected, and so was that of the Public Service. As a Permanent Secretary under that Constitution during the first two years of my seven-year term, I had the freedom to supervise the departments assigned to the Ministry, subject only to policy directions from my Minister. On one occasion when I refused to comply with a specific non-policy direction, I was reported to the Prime Minister who, fortunately, had a clearer understanding of constitutional principles.

The constitutional Head of State

For 30 years, the constitutional Head of State was the principal unifying figure in the country; the non-partisan, independent, symbol of the State. Opposition parties could approach the President in the knowledge that he was a neutral figure. When, in 1972, a conflict developed between the Constitutional Court and the National State Assembly, and the Judges refused to speak to the Speaker or the Ministers, it was at President’s House that each party sat on either side of the conference table, with the President at the head, to commence a dialogue to try to resolve their differences. That exercise, however, failed.

When, in 1976, following a long period of “cold war” between the Supreme Court and the Ministry of Justice, the Minister decided it was time to break the ice, and invited the Chief Justice and other Judges of the Supreme Court to the Ministry to tea, it was to President’s House that they proceeded instead, to complain of the invitation, which they perceived to be an interference with the judiciary. William Gopallawa was not a mere ceremonial president; he was not a mere cipher. I was summoned by him on several occasions when he disagreed or felt uncomfortable with advice tendered to him, either by a Minister or the Prime Minister. He did not hesitate to invite the Prime Minister, or the Minister concerned, to reconsider the advice.

The presidential executive system

That parliamentary executive system of government was replaced in 1978 by a presidential executive system of government, not because the former, which prevails to this day in democratic countries from Canada and the United Kingdom, through India, Singapore, and Malaysia, to Australia and New Zealand, had somehow failed the people of Sri Lanka. It was replaced not because the people of Sri Lanka cried out aloud nostalgically for a return to some form of monarchical rule. It was replaced because that was the wish and desire of one senior political leader who probably sincerely believed that that was the best form of government for our country.

However, from 1966, during the next seven years, J.R. Jayewardene failed to convince his party leader, Dudley Senanayake, of his strong belief that an Executive President chosen directly by the people, seated in power for a fixed number of years, and not subject to the whims and fancies of an elected legislature, was what the country required.

He also proposed an electoral system where there were no electorates; where each political party presented a list of candidates; where the voter voted for the party; and the legislators were chosen from that list, the number depending on the votes cast for each party. He predicted that that system would enable the best equipped men and women in the country to take part in our political life. Little did he know that 50 years later the “best equipped men and women” would include 90 parliamentarians who had not even attempted to sit the GCE “O” Levels. Prime Minister Dudley Senanayake did not support this proposal; nor did the UNP Working Committee.

At the general election of July 1977, when he led his party to an unprecedented five-sixth majority in the National State Assembly (NSA), Prime Minister Jayewardene was able to fulfil his dream project. In October of that year, a Bill to amend the Constitution, certified by his Cabinet as being “urgent in the national interest”, which sought to transfer all the executive powers of the Prime Minister to the President, and for the incumbent Prime Minister to be deemed the first nationally elected President, was passed by the NSA. On 4 February 1978, that constitutional amendment was brought into force, and Jayewardene was sworn-in on Galle Face Green as the first Executive President of Sri Lanka.

Meanwhile, a Select Committee of the NSA was established to consider the revision of the 1972 Constitution. At the concluding stages of that Committee, the Government tabled a wholly new draft constitution, the author of which was not disclosed. On 31 August 1978, with the TULF and the SLFP walking out, and with none voting against, the NSA enacted the Constitution of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. On 8 September 1978, the new Constitution was brought into operation, and the 168 members of the NSA were deemed to have been elected as Members of the new Parliament that was established.

Parliamentary majority essential

The 1978 Constitution, under which the President was the source of all power and patronage and was beyond the reach of the law and the judiciary, was a Constitution of Jayewardene, by Jayewardene, for Jayewardene. Dr. Colvin R. de Silva’s prescient plea that he should not bequeath it to his successors, was ignored. The success of his project, however, was entirely dependent on one essential factor – that the President elected by the people was supported by a clear majority in the Parliament elected by the people. I attended a few meetings of the select committee as an adviser to Mrs Bandaranaike and Maithripala Senanayake, since neither of them was a lawyer.

At one of the meetings, I had occasion to ask Jayewardene what the position would be if a political party opposed to the President secured a majority in Parliament. He thought that would be unlikely during his term of office, but if that were to happen, he said he would take a step back and be a constitutional Head of State. He, of course, ensured that that did not happen during his presidency by securing an extension of the life of Parliament for a further six-year term through an amendment of the Constitution, a rigged referendum, and through many other devices such as obtaining undated letters of resignation, maintaining secret files on the financial and other activities of his Ministers, and by imposing civic disabilities on his political opponents.

His successors, however, were either not so fortunate, or did not possess his political acumen. In August 1994, UNP President Wijetunge, faced with a Parliament in which the United Front had a majority, chose to take a step back to spend the last three months of his term as a constitutional Head of State. In 2001, President Kumaratunga, faced with a Parliament controlled by the UNP, chose “cohabitation” for a while, and then used her presidential powers to dissolve Parliament prematurely, having previously assured the Speaker that she would never do that while a political party other than her own commanded a working majority. In the next 10 years, both she and President Rajapaksa regularly lured Members of the Opposition to secure the majority which they required, using methods that should have alerted any self-respecting Bribery Commissioner and kept him awake at night.

One does not need to be reminded of the shambolic relationship that prevailed between the President and the Prime Minister in the “Yahapalana” Government; nor of the inconceivable situation today where the President is compelled to function with a Cabinet of Ministers and a parliamentary majority politically opposed to him.

A political consensus exists

For over 30 years, every major political party has pledged to restore the parliamentary executive form of government. For that purpose, every major political party has supported the election of the President by Parliament (or other representative body).

In 2000, President Chandrika Kumaratunga, as head of the SLFP Government presented a draft Constitution which provided for the President and two Vice-Presidents (the latter drawn from ethnic communities different to that of the President) to be elected by Parliament.

In 2013, the Ranil Wickremesinghe-led UNP published the text of the principles upon which a new Constitution would be formulated after it forms a government. Among them was that the Executive Presidency would be abolished.

In 2015, President Sirisena stood before the casket bearing the remains of the late Rev. Maduluwawe Sobitha and, with his head bowed, swore an oath that he would ensure that all remnants of executive power would be removed from the office of the President of the Republic.

In 2018, a panel of experts appointed by the UNP/SLFP Yahapalana Government led by President Sirisena and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe prepared and published a draft Constitution which required the President to be elected by Parliament and to exercise many of his/her powers on advice.

In 2018, the JVP headed by A.K. Dissanayake, presented a Bill to amend the Constitution to enable the non-executive President to be elected by Parliament.

In 2021, the SJB led by Sajith Premadasa proposed an amendment to the Constitution to enable a non-executive President to be elected by Parliament.

A referendum is not required

The 1978 constitution introduced for the first time into the Sri Lankan constitutional process the concept of a referendum. In the tradition of the Greek city states, actual decision-making was being restored to the people. The articles of the constitution which Parliament may not amend without approval at a referendum are regarded as the fundamental elements of the State and are explicitly set out in Article 83. They are: its name (art. 1), its unitary character (art.2), the inalienability of the people’s sovereignty (art.3), its national flag (art.6), its national anthem (art.7), its national day (art.8), the foremost place accorded to Buddhism (art.9), the freedom of thought, conscience and religion (art.10), the prohibition of torture (art.11), any extension of the term of office of the President (art.30), and any extension of the life of Parliament (art.62).

The introduction of a referendum appears to have been intended as a means of ensuring that these fundamental elements would ordinarily remain unaltered. In that regard, the Constitution has distinguished the principle from its implementation. For example, while the life of Parliament or the term of office of the President cannot be extended without approval at a referendum, any reduction of the life or term can be achieved by an amendment passed in Parliament. Similarly, while the concept of the people’s sovereignty is unalterable (thus preventing its alienation to a monarch, a military officer or to a particular community), the manner of its exercise is left to be determined by Parliament. Thus, a requirement that the executive power of the people be exercised by the President on the advice of the Prime Minister is an amendment capable of being made by Parliament by a two-thirds majority without reference to a referendum, as was held by the Supreme Court in 2015.

Unfortunately, the decision of the Bench of three Judges of the Supreme Court (Chief Justice Sripavan and Justices Ekanayake and Dep) on the 19th Amendment which enabled Parliament to amend the Constitution to require the President to act on the advice of the Prime Minister in respect of several matters, has not been followed in subsequent determinations. For example, the proposal made in 2019 by the JVP that the impending election to the office of the then non-executive Presidency be by a majority vote in Parliament was rejected by the Supreme Court.

Justice De Abrew held that that would violate Article 4, and that any amendment of Article 4 requires approval by the people at a referendum. Article 4 is not an entrenched provision specified in Article 83. He also ignored the fact that Article 40 of the Constitution already provided for Parliament to elect the President in certain circumstances.

Replacement of list-system with constituencies

The election of members of parliament from 25 district lists, based on proportional representation, was introduced by J.R. Jayewardene as an integral element in the presidential executive system of governance. Since each district encompassed several former constituencies, the expenditure involved in campaigning in such a large extent of territory, and the need to raise money for that purpose from various sources, inevitably on a quid pro quo basis, has been identified as one of the principal factors leading to corruption. The return to the single-member/multi-member constituencies, combined with a system of proportional representation to ensure that unrepresented interests are adequately represented, ought to be an essential adjunct to a parliamentary executive system of governance.