Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Thursday, 18 January 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

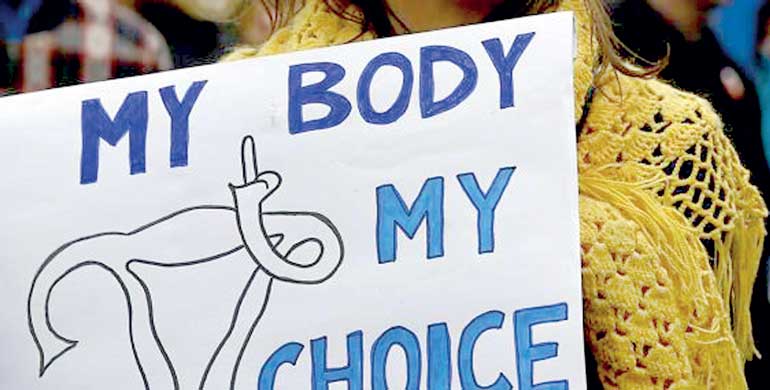

Sri Lanka’s 130-year old anti-abortion law is clear: aborting a pregnancy except to save the life of the mother is a crime.

Section 303 of the Penal Code states: “Whoever voluntarily causes a woman with child to miscarry shall, if such miscarriage be not caused in good faith for the purpose of saving the life of the woman, be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to three years, or with fine, or with both; and if the woman be quick with child, shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to seven years, and shall also be liable to fine.”

The fact of the matter, however, is that abortion is commonplace. The most recent national study, a UN Population Fund-sponsored project in the late 1990s, estimated that some 650 abortions take place each day, country-wide [see Source 1, below]. The rate now is conservatively estimated to exceed 1,000 a day. Indeed, in a 2009 paper [2] Dr N.L. Abeyasinghe of the Department of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology of the University of Colombo estimated that for every 1,000 children born, another 740 had been aborted.

The law, which dates to 1883, thus not only makes criminals of hundreds of thousands of women annually but, because the medical profession is forbidden to administer abortions, forces women into the hands of unscrupulous quacks. Frequently the abortion is botched and the mother, in addition to losing her baby, ends up in hospital.

The Ministry of Health’s ‘Annual Health Bulletin’ (2001) estimated that 7-16% of female admissions to Government hospitals are the result of a botched abortion. That amounts to more than 100,000 hospitalisations annually: a huge toll on the hard-pressed national healthcare budget, and a huge cost (including dozens of lives lost annually) to womankind.

Because the whole idea of abortion is illegal, health workers cannot even offer counselling on this subject to prospective mothers (it would be aiding and abetting an offence). For the same reasons, neither can abortion be included in the schools sex-education curriculum. In short, the whole issue of abortion has to be swept under the carpet and, as a consequence, has become a source of unmitigated misery for millions of Sri Lankan women.

Unsurprisingly then, the Ministry of Health, numerous women’s-advocacy groups and the World Health Organisation itself, have long been lobbying for a reform of the law. They recognise the fact that despite it being a criminal act, about 1,000 women have an abortion every day. Their goal is to make abortion safe and, through effective family-planning counselling, to reduce the abortion rate itself.

The bill making the relevant amendments to the Penal Code, however, has had a painful history. Many politicians, ethicists and religious leaders are opposed to it. They do not want to open the stable doors to abortion at will, a concept clearly alien to Sri Lanka’s Buddhist heritage and its deep reverence for all life. Those who favour reform argue, however, that legalising early-term abortions, at least in special cases (discussed below), would allow the subject to be drawn into the sex-education curriculum, thereby improving awareness and leading to a decline in the abortion rate itself.

Agonising choice

As the law stands, even women who become pregnant as a result of rape must carry their babies to term. In fact, Dr. Abeyasinghe’s study [2] showed that more than 75% of women interviewed felt that abortion should be legalised if the mother was psychiatrically ill or had been a victim of rape or incest, or when there were foetal anomalies.

The decision to abort a pregnancy is surely among the most agonising choices ever to confront a woman. No one would make this decision lightly. But the fact of the matter is that almost 400,000 Sri Lankan women resort to abortion annually: that is a staggering figure that simply cannot be ignored. Putting all these women in prison is not an answer. The issue of abortion has to be addressed through a reform of the law.

‘Morning-after’ pill

The tragedy of abortion in Sri Lanka is that it is not usually an issue that confronts the better-educated well-to-do readers of English newspapers. They and their teenage daughters have ready access to information on contraception.

Should unexpected sex occur, whether consensual or forced, they know to rush to the nearest pharmacy and buy themselves a dose of Postinor (levonorgestrel), the so-called morning-after pill (a misnomer, because they are most effective if taken within 12 hours of sex and so are better termed emergency contraceptives). Depending on which clinical study one reads, this reduces the risk of pregnancy by over 95%. Levonorgestrel is cheap (around Rs. 150) and can be obtained without a doctor’s prescription.

In the event levonorgestrel does not work (usually because it is taken too late), a pregnancy may occur. This would usually be detected after the patient has missed her first period after the sexual encounter and had a positive result in a pregnancy test; i.e. she is clinically pregnant. In that event an abortion is called for, it is possible within the first nine weeks of implantation to have a ‘medical abortion’ using RU486 (Mifepristone), under medical supervision.

I suspect that in Sri Lanka, as elsewhere, most ‘illegal’ abortions take the RU486 route. However, unless taken under proper medical supervision, the RU486 or the surgical options can result in serious complications resulting in hospitalisation of the mother. This leads to a double standard [4] in which the rich, with access to private health care, are at a huge advantage against the poor, who must necessarily turn to a quack.

Ethical landscape

Short of the extreme position that a pregnancy may never be aborted, is there an ethical space in which an early-stage abortion should be permitted? The worldwide acceptance of levonorgestrel suggests that for millions of women, terminating a potential pregnancy within three days of the sexual encounter is acceptable. RU486 offers a safe and reliable option to terminate the pregnancy shortly after it is clinically detected. Both these options are available for pregnancies of up to nine weeks’ duration, and no person would argue that a nine-week foetus is sentient in any sense of that word.

Until the 1980s, pregnancy tests could only detect a pregnancy after about six weeks had elapsed from the previous menstrual period (i.e. about a month after conception). Today, tests for hCG (a hormone) in the patient’s urine can detect pregnancy within a few days of implantation. As a result, we now know that about 30% of all conceptions result naturally in an ‘early pregnancy loss’: i.e., the mother discharges the foetus spontaneously [5].If 30% of all conceptions end naturally in spontaneous abortion, then surely early-stage physician-induced abortion itself cannot be such a terrible thing?

Given that Nature already terminates 30% of pregnancies, the ethical question before us is not so much whether abortions are acceptable as when (i.e. how many weeks after implantation).Clearly most people would be horrified by the idea of aborting a late-stage pregnancy. But an ethically acceptable alternative to criminalising hundreds of thousands of women would be to allow them (say) within the first nine weeks to have a safe abortion performed by a qualified doctor. In almost all these cases, this would mean taking medication as opposed to resorting to surgery.

Education and counselling

It is also fitting to ask why so many unwanted pregnancies occur in Sri Lanka. Much of the demand for abortions comes from married women with two or more children who do not want to have yet another one. Family-planning guidance and education then, are a key factor (as is awareness of the use of levonorgestrel).

We also need to recognise that young people nowadays are engaging in sex much earlier than previously thought. An island-wide survey of more than 3,000 Grade 12 and 13 students [6] found that almost 60% of boys and 30% of girls aged 19 had had sex. What is more, about 20% of youngsters reported having been in a “forced sexual experience” (i.e. rape). If that many 19-year old girls admit to having been forced into sex (bear in mind that many more would be too ashamed to admit it), the chances are that a fair proportion of them become pregnant: a rapist, after all, is unlikely to prepare for his crime by first donning a condom. How much worse is the girls’ plight if they have to have their abortions performed by quacks and cannot even confide in their mothers?

Sri Lanka needs to face up to the fact that its citizenry is engaged in sex in a diversity of scenarios, greatly increasing the risk of unwanted pregnancies (and, by the way, sexually-transmitted diseases). What is needed then is a sound curriculum of sex education in schools (the level of ignorance is astronomical [7]), equipping young people to deal with these challenges.

Girls need to be taught the facts of life as soon as they have their first period, and most importantly, what to do if they end up having unprotected sex. The need of the hour is not for obtuse pontification but for a sympathetic realisation of the plight of hundreds of thousands of women in Sri Lanka who face a dreadful predicament and to devise ways in which they can be helped [2]. Imprisoning hundreds of thousands of women may well be the only solution the law offers, but surely we can strive for more enlightened values than that?

On the bright side, there are signs that even the Catholic Church, hitherto a strident opponent of reform, is softening its stance on the issue. “We cannot insist only on issues related to abortion, gay marriage and the use of contraceptive methods,” Pope Francis was reported as saying [8], in a conciliatory tone similar to that he adopted when asked about gay clergy in the church: “Who am I to judge?”

The Pope clearly understands the meaning of the word “Catholic” (universal) in the name of the church he heads. “This Church with which we should be thinking is the home of all, not a small chapel that can hold only a small group of selected people,” he was quoted as saying. “We must not reduce the bosom of the universal Church to a nest protecting our mediocrity.” A sign, perhaps, that the church in Sri Lanka will not stand in the way of the proposed reforms? Then again, maybe not.

Sources

[1] Rajapakse, L. C. 2002. Estimates of induced abortion in urban and rural Sri Lanka. Journal of the College of Community Physicians of Sri Lanka,7: 10-16.

[2] Abeyasinghe, N. L. 2009. Awareness and views of the law on termination of pregnancy and reasons for resorting to an abortion among a group of women attending a clinic in Colombo, Sri Lanka. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 16: 134–137.

[3] http://www.island.lk/index.php?page_cat=article-details&page=article-details&code_title=48619 [4] Kumar, R. 2013. Abortion in Sri Lanka: The double standard. American Journal of Public Health, 103(3): 400-404.

[5] Wang, X. et al. 2003. Conception, early pregnancy loss, and time to clinical pregnancy: a population based prospective study. Fertility & Sterility, 79: 577-84.

[6] Perera, B. & Reece, M. 2006. Sexual behavior of young adults in Sri Lanka: Implications for HIV prevention. AIDS Care, 18(5): 497–500.

[7] Thalagala N. 2004. National Survey on Emerging Issues Among Adolescents in Sri Lanka. Colombo, Sri Lanka: United NationsChildren’s Fund. <http://www.unicef.org/srilanka/Full_Report.pdf>

[8] La CiviltaCattolicato, Issue 3918 (September, 2013).