Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Wednesday, 19 June 2024 00:20 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sri Lanka being called upon by Adani to pay about $ 1,200 million extra over the next 20 years, requires more explanation than quoting tweets

I write with reference to the article in Daily FT of 7 June 2024, titled “Adani sets the record straight” (https://www.ft.lk/front-page/Adani-sets-record-straight-on-wind-power-project-in-Sri-Lanka/44-762766).

I write with reference to the article in Daily FT of 7 June 2024, titled “Adani sets the record straight” (https://www.ft.lk/front-page/Adani-sets-record-straight-on-wind-power-project-in-Sri-Lanka/44-762766).

Adani would have thought Sri Lanka has no energy economists or power system engineers, or would have wrongly assumed that all Sri Lankan professionals were as mediocre as the politicians or the handful of administrators and engineers in the power sector and its two regulatory institutions they directly deal with.

Insulting the wisdom of Sri Lankan public and professionals, on 7 June 2024, Adani made a completely wrong comparison between their negotiated price of 8.26 USCts/kWh for his wind power project, and “costs” of several other types of power plant in Sri Lanka. Hilariously, Adani sourced his own price of 8.26 to a tweet of the Minister, displaying the loose thread his project is hanging on, so much to say that the “the Minister tweeted my price to be 8.26, not me”!

Similarly, all other costs of electricity production Adani compared his price with, are irrelevant since they are simply not comparable. An oil power plant does a backup duty, and its costs are high, even in India. Wind power generation is seasonal, same as hydropower. Solar power is diurnal and hydropower is seasonal, too. Adani cautiously avoided comparing his figures with hydropower and coal power. Why not?

Be that as it may, let us first trace how the wind power project of Adani came into being, in the first instance. Then we will examine the price offered and defended by Adani.

Be it to Ministry of Power, President’s house or to Public Utilities Commission, purchase of even a packet of paper clips requires three price quotations. For larger purchases, competitive offers are called based on pre-defined specifications and a format, submitted by a specific date and time, and then opened and prices publicly announced. For high value purchases, such as a power plant or a power purchase agreement (PPA), there has to be a pre-qualification process, separate technical and financial proposals are then called for from qualified bidders, and the Cabinet-appointed tender board makes the final decision. Even in India, that is the procedure. The source of information to bidders is the Tender Board, not ministerial tweets.

Alas! In Sri Lanka, to procure a wind power plant rated at 454 MW producing 1,590 million units of electricity per year for 20 years, at a negotiated price of 8.26 USCts/kWh, meaning a contract with a value of $ 2,600 million, there was no competitive bid. Excellent, isn’t it? To say the least, it is alarming.

However, from time to time, games have been played by Presidents, Ministers and their cohorts in Ministry of Power and Energy (MOPE), Sri Lanka Sustainable Energy Authority (SLSEA) and CEB, too, to bypass the bidding procedure. Almost all of these attempts have failed in the electricity sector. For example, a Minister in the early 1990s wanted CEB to buy a diesel power plant that was not in any plan, to be installed in his constituency, without a bid. He failed and was prosecuted under the subsequent Government, but the Minister passed away before the court case was concluded.

A Secretary to the Treasury and his self-styled Secretariat for Infrastructure Development (SIDI) in the mid-1990s pressurised CEB to issue a letter of intent to a company previously unheard of, to build a coal power plant in Trincomalee. This Canadian company, run by one person but had never built a single power plant in the world before or thereafter, could not proceed with the project. Yet they sued the Government of Sri Lanka through an international arbitration. Sri Lanka AG’s department and its fine lawyers challenged the case, and Sri Lanka won. Mihaly International Corporation v. Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka (ICSID Case No. ARB/00/2) decided in favour of Sri Lanka on 15 March 2002.

More recently, a case with similar flaws for another wind power plant, too, has undergone the same fate (it was never built), unsuccessfully filed an arbitration case against the Government, but a formal announcement on the outcome of arbitration proceedings is yet to come from the Government. Therefore, hoodwinking the public of Sri Lanka, especially about power projects, have been met with drastic consequence to the project proponents, and their local pushers, be it within or outside the Government, MOPE, SLSEA, PUCSL or the CEB.

The Government can be reminded about the infamous and often referred to as the mid-night deal, “New Fortress” gas terminal and supply of natural gas, the most recent attempt to bypass the competitive procedure, which was the beginning of the fall of the presidency and Government of 2020.

Adani drama unfolded in three acts

The first act that paved the way of the likes of Adani drama was played in 2013, when the then Secretary to MOPE, caused an amendment to the Electricity Act 2009 to be moved in Parliament, which said the following: a power generation project for which an “an offer received from a foreign sovereign Government to the Government of Sri Lanka, for which the approval of the Cabinet of Ministers have been obtained” needs not go through a competitive bidding process. This amendment to the law looked very innocent and innocuous because friendly governments have always provided extremely concessionary terms for power projects proposed by them or presented by Sri Lanka to them for financing (e.g.: Victoria power plant 1984: free from UK Govt., and the most recent Upper Kotmale Power Plant 2013 at 0.25% interest rate, 40-year repayment terms from the government of Japan). Therefore, this amendment and a few other corrections to the 2009 Act went through parliament in 2013 and did not create much news.

The second act of the Adani drama came into being in 2021 when the same Secretary, now appointed CEB Chairman, admitted when questioned at a COPE meeting in Parliament, that a proposal from Adani to build a wind power plant in Mannar without a bid, has been entertained. He stated that the (then) President said that “PM of India wanted this done”, but hours later, he retracted his statement. The President’s office immediately denied this claim. The apparently gullible members of COPE, including the opposition now shouting from the rooftops that Adani deal is too expensive, defended the CEB Chairman, and allowed the long-serving public servant to withdraw his most controversial statement. CEB Chairman later resigned.

That ended the second act of the Adani drama, but the drama did not end there. The new administration continued, and extended the drama by tabling in June 2022, yet another amendment to the Electricity Act of 2009, to remove the 25 MW limit for private power projects and to additionally say, “If Sustainable Energy Authority has approved a project, then there is no need for competitive bidding”. The gullible or conniving MPs who raised their hands to this amendment did not know that the purpose was to push more renewable energy projects through the back door, without competitive bids.

The third act of the drama was when Adani was requested by MOPE, to fill-up a document, in the format a competitive bid would have been, but only Adani was given that book, no one else. So, it was not transparent, not competitive, not open. That is an attempt to legitimise a backdoor entry, so that the Minister, when questioned in Parliament can say “Adani submitted a bid”. Lo and behold, he did say so many times in Parliament, not only about Adani but about dozens of dubious projects that have come through the backdoor, but through a seemingly legal document issued through the front door. Other investors were made to go from pillar to post, not knowing whether their project was in or out. Confusion, not clarity, is what decision-makers in Sri Lanka thrive on.

Finally, to accommodate Adani, there was a hitch. According to the 2013 amendment to the Electricity Act, there is a requirement for the proposal to come from a sovereign government, if it is to be entertained without a competitive bid. So, the Minister did the simplest thing: filed a Cabinet paper in August 2023 which literally said: Adani = Government of India. Alas, Sri Lanka’s cabinet approved the paper, with no questions asked.

However, several media channels on 9th June 2024, quoted His Excellency Santosh Jha (Indian High Commissioner to Sri Lanka) to say: “It is a commercial venture by Adani. The proposed construction of a wind power station on Mannar Island should progress after a better negotiation process”. So, the message of the High Commissioner is clear; it is not a government of India proposal but a commercial project promoted by Adani, and hence does not qualify to go without a competitive bid, under the Section 43(4)(b) of Sri Lanka Electricity Act 2009 (as amended in 2013).

Meanwhile, the Sri Lanka Electricity Act 2024 was approved in Parliament on 6 June 2024, after much debate. There too, the MOPE that drafted the Bill, said that if an approval of the Cabinet of Ministers has been received before this act comes into operation, then such project need not go through competitive bidding (hoping that all the back-door projects can be hurriedly approved by the Cabinet before the “appointed date”). The Supreme Court was emphatic: they declared the clause to be unconstitutional, added a provision “provided that the selection of the party to whom the approval has been granted or the letter of award has been issued, has been selected pursuant to a transparent and competitive procurement process”.

What is the fair price for wind power?

While legal experts argue whether there can actually be a project called “Adani Wind Power” in the current manifestation of the Electricity Act, let us examine whether Adani’s attempt to set the pricing record straight in FT article on 7 June, was successful.

Since there was no transparent and competitive bidding process, there isn’t a “form of bid” in the public domain. Sri Lanka’s private power projects are procured by requesting bidders to fill-up an extensive format, stating their investment on the project, debt:equity ratio, debt repayment plan and interest rates, letters of support from bidder’s banks, expected return on equity, and maintenance costs. If done so, the bidder’s costs are known for each year of the contract period.

The benefit to the grid is the energy (in units of electricity) it will produce. Units of electricity produced must match with the best similar power plant in the region, or should be better, since wind power equipment capacity, height and diameter are increasing all the time, making one turbine capture more energy, hence more “efficient”.

So, if there was an open bid, we have the annual costs and annual benefits. No information is available on how the annual costs and annual benefits (electricity) were converted to a single “headline” price of 8.26 USCts/kWh, which Adani says is reasonable. The industry practice is to use a discount rate (usually defined by the buyer, in this case the CEB) and take the ratio between the present value of costs and present value of benefits, at the declared discount rate. This answer is called “the levelised price”.

If there was a competitive bidding process, the method of calculation would have been open, all bidders would have filled-up a pre-defined spreadsheet and at the public opening of bids, the “levelised price” would have been announced in front of all bidders.

Sadly, although the law says otherwise, there was no such public announcement of bids, because there were no bids. There have been only some internal reports, which are not open to the public. Yet, there is adequate knowledge in the public domain about how much a wind power plant costs and how much of electricity it should produce in Mannar.

This disclosure uses such information in the public domain. Let us consider the Mannar 250 MW power plant the Government hails as a good project, to be awarded to Adani. Adani project includes another wind power plant in Pooneryn but let us consider only the Mannar project.

So, here we go with the calculations.

For wind projects less than 10 MW, Ministry of Power and Energy uses an investment benchmark of $ 1,100 per kilowatt of capacity, since year 2022. For its own wind power plant in Mannar, CEB reportedly spent $ 140 million to build 103 MW, which works out to $ 1,354 per kilowatt of capacity. Let us use the higher of MOPE and CEB figures, CEB’s reported unit cost 1,354 x 250,000 = $ 338 million as the investment for Adani wind power project in Mannar.

This investment is typically financed by debt and equity, and as typical for many projects, let us assume 70% of the project cost to be debt-financed in USD, repayable in equal instalments over 10 years at an interest rate of 8% per year. The equity portion brought-in by Adani will be 30% of the investment; a decent, legitimate investor expects a return of about 14% per year on his equity, in a country like Sri Lanka, where risks are perceived to be higher. An investor in USA may be happy with about 8% return on equity.

Now we come to the cost of maintenance. MOPE uses a figure of 2% of capital costs spent on maintenance every year, to calculate feed-in-tariff for small power plants of less than 10 MW. CEB reported their maintenance costs were about $ 3 million (including the outsourced costs and internal costs) for the $ 140 million power plant already operating in Mannar. That works out to 2.1% of the investment spent every year. So let us use the CEB’s figure of 2.1%. Now this cost escalates every year; being denominated in USD, it has to escalate by the forecast USCPI, which, giving the benefit of the doubt to Adani, let us assume to be 2% per year. So, the maintenance cost will increase by 2% every year.

Now we have the cash required by Adani, to pay debts, interest, maintenance and profits, every year, for 20 years, on the Mannar 250 MW project. Say in year 1, the money needed by Adani will be the following:

Total cash required = $ 64.2 million

This money has to be earned by selling electricity to CEB. The quantity of electricity produced depends on the wind speeds, turbine height and diameter, and the overall “efficiency” of conversion of wind power to electricity. CEB reported in 2022, that their power plant achieved an annual capacity factor of 40% (CEB Sales and Generation Data Book, 2022). This includes shutdowns owing to radar detection of potential bird strikes. CEB and Adani must have a lot better data about the expected capacity factor. Our experience says that for the Mannar wind zone, using modern wind turbine-generators, the capacity factor must be about 44%, unless Adani does a completely wrong design. Yet to give the benefit of the doubt to Adani, let us say Adani power plant also operates at 40% like the CEB power plant. That means it would produce 250,000 x 8760 x 0.4 = 876 million units of electricity in its first year of operation.

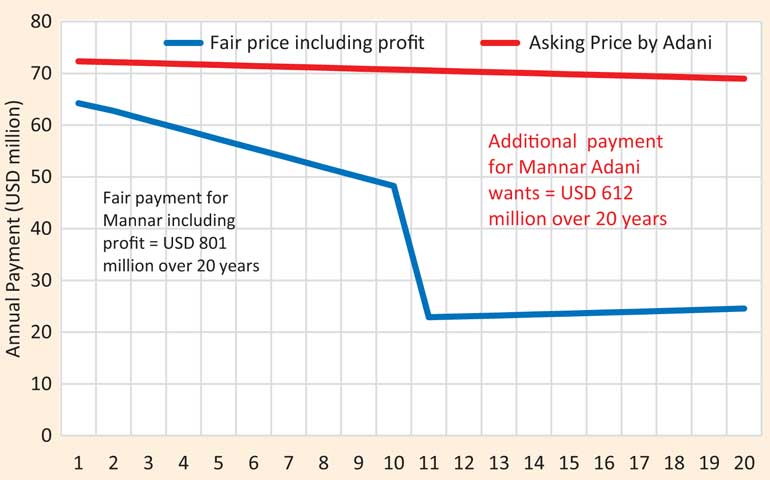

So to earn $ 64.2 million in year 1 (including a profit), Adani needs to sell electricity to CEB at 64.2/876 which works out to $ 0.0733 per unit or more conveniently stated as 7.33 USCts/kWh.

As time passes, maintenance costs increase, and electricity output decreases slightly, as equipment aging sets in. We have assumed energy output to reduce by 0.25% every year, meaning that by the 20th year, the production of 876 million units will be lower by 5%.

There is a breakpoint in the cash requirements in year 10, when the loan is fully paid off.

So, selling prices of Adani to CEB would have to be:

Year 1= 7.33 UScts/kWh

Year 1 to 10: O&M increases, energy reduces, loan interest amount reduces

Year 10 = 5.64 USCts/kWh

Loan is fully paid off

Year 11 = 2.68 USCts/kWh

Year 11 to 20: O&M increases, energy reduces, no loan to be paid

Year 20 = 2.94 USCts/kWh

So what Adani has to say is: “pay me 7.33 USCts/kWh in year 1, declining to 5.64 in year 10, steeply dropping to 2.68 in year 11, gradually increasing to 2.94 by year 20”.

The industry practice is to levelise these annual costs and indicate the price as one number. Since there was no open, transparent, and competitive bidding process, we have no way to know the basis of calculations, but we can safely assume that the discount rate used was the weighted average cost of capital, which will be 70% x 8% + 30% x 14% = 9.8%.

Therefore, the present value costs (that means the income required by Adani’s Mannar 250 MW wind power plant) starting at $ 64.2 million in year 1 ending with $ 24.6 million in year 20 (all costs and profits included), will be $ 415.1 million. The present value of energy benefit will be 7438 GWh.

So the levelised cost (therefore the tariff) of the 250 MW Adani project must be 415.1/7438 = $ 0.0558 per unit meaning 5.58 USCts/kWh.

That’s it. Now to set the record straight, Adani can explain how 5.58 increased to 8.26 (a 48% increase), drawing an extra 2.68 USCts/kWh, equivalent to an extra $ 612 million (undiscounted) over the 20 years from Mannar alone. Pooneryn will be similar.

So, Sri Lanka being called upon by Adani to pay about $ 1,200 million extra over the next 20 years, requires more explanation than quoting tweets from Sri Lanka’s MOPE. Therefore, Adani has to truly set the record straight by explaining: