Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday, 1 July 2022 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Extreme heat and heat stress can severely affect human health and wellbeing, especially in urban environments and tropical climates

Extreme heat and heat stress can severely affect human health and wellbeing, especially in combination with high humidity. Tropical countries such as Sri Lanka are therefore at heightened risk

Extreme heat and heat stress can severely affect human health and wellbeing, especially in combination with high humidity. Tropical countries such as Sri Lanka are therefore at heightened risk

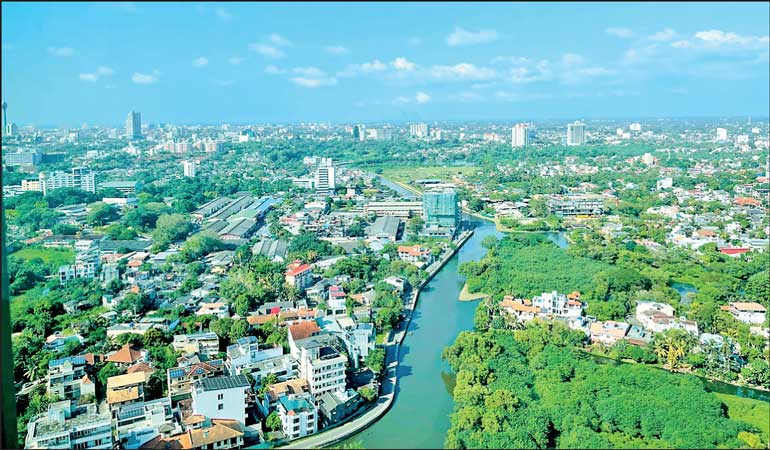

from rising global temperatures, with urban populations—for instance in Colombo—among the most vulnerable and exposed. However, there is a range of possible actions and interventions to mitigate increasing temperature, counteract the urban heat island effect, and cool down cities to protect humans, animals, and the environment.

Urban heat in the context of climate change

Average temperatures are rising around the globe, and every new decade since the 1980s has been warmer than the previous one. As reported by the State of the Global Climate 2021 published by the World Meteorological Organization in May, “the most recent seven years, 2015 to 2021, were the seven warmest years on record,” and global mean temperatures in 2021 were “1.11 ± 0.13 degrees Celsius above the 1850–1900 average.”

The report further states that “the acute impacts of weather and climate are most often felt during extreme meteorological events such as […] heatwaves,” and that heatwaves and extreme heat had devastating effects and caused deaths across different world regions, which in many cases would have been “virtually impossible without climate change.”

Global warming leads to more frequent and intense heatwaves as well as extended periods of high temperatures, which can harm human health, wellbeing, and livelihoods. In particular, already vulnerable or weakened groups, such as the elderly, children, or the economically disadvantaged, are at risk of severe impacts that can worsen chronic respiratory or cardiovascular conditions and even lead to death. Furthermore, natural ecosystems, biodiversity, agricultural productivity, and many other aspects of human society and economy can be adversely affected by heatwaves and heat stress.

Due to the “urban heat island effect,” cities and urban agglomerations are hit especially hard by these rising temperatures. They become hotter than rural areas because of their population density, the higher concentration of “sealed” surfaces that absorb and retain heat, and other factors such as air pollution. For Colombo, it has been estimated that average temperatures may have already risen by 1.6 degrees Celsius due to the heat island effect, which would be significantly higher than the global average. For Sri Lanka as a humid tropical country, this poses the danger of lethal “wet bulb” temperatures, which are caused by a combination of high temperature and humidity and prevent the human body from cooling itself by evaporating sweat.

The 11th World Urban Forum (WUF11), which just took place in Katowice, Poland, also highlighted the importance of recognising and addressing climate change in urban planning. Building resilience for sustainable urban futures, transforming cities through innovative solutions, and enhancing climate adaptation and nature-based solutions were among the key dialogue topics of the five-day global conference, which is convened every two years by the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat).

Adapting to urban heat and building resilience

The urban heat island effect in the context of rising global temperatures poses a serious threat that needs to be addressed by incorporating heat stress management into policies and action plans and address impacts to health and productivity through social protection schemes and infrastructure development. Weather forecasting, early action, and monitoring can also play a big part in enhancing heat wave response, especially if they are combined with awareness creation and education on potential risk factors, symptoms, responses, and treatment options. Other collective resilience-building measures can include heat hotlines, community check-ups, or community cooling centres.

In addition to this, heat adaptation encompasses a range of nature-based interventions and actions. For one, making cities greener tends to make them cooler as well, as plants provide shade as well as cooling through evapotranspiration. This can include urban forestry—planting more trees and generally increasing the vegetation cover—as well as the development of green corridors, parks, and rooftop gardens. Such green infrastructure also offers a range of co-benefits beyond lowering temperatures for cities, including erosion control, emission reduction, and improvement of air quality.

Heat-resilient cities can be green, blue, or blue-green. Urban wetlands are powerful nature-based solutions for managing heat stress as well as water quality and protecting against flooding and stormwater runoff. Revitalising urban streams, watercourses, or lakes can also pay off in many ways, including by providing cooling and other ecosystem services. Other possible actions include cool roofs and pavements—using materials that reflect more solar energy and enhance water evaporation—or infrastructure planning that takes into account “natural” wind and urban ventilation corridors.

What many of these solutions have in common is that they view the urban environment as an ecosystem that consists of more than just streets and buildings, and which is deeply interconnected with natural and social systems. They aim at creating greater awareness and enhance adaptive capacities while also conserving natural ecosystems, which can serve as a low-cost way to protect the natural environment as well as human communities from heat stress and heat-related impacts. With holistic and integrated planning, cities like Colombo can reduce days of extreme heat and avert heat-related deaths as well as other serious impacts to labourers, families, the urban poor, and vulnerable groups.

(The writer works as Director – Research and Knowledge Management at SLYCAN Trust, a non-profit think tank based in Sri Lanka. His work focuses on climate change, adaptation, resilience, ecosystem conservation, just transition, human mobility, and a range of related issues. He holds a Master’s degree in Education from the University of Cologne, Germany and is a regular writer to several international and local media outlets.)