Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Friday, 21 June 2024 02:35 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

In 2024, all three Rio Conventions are convening to address their respective aspects of the global polycrisis

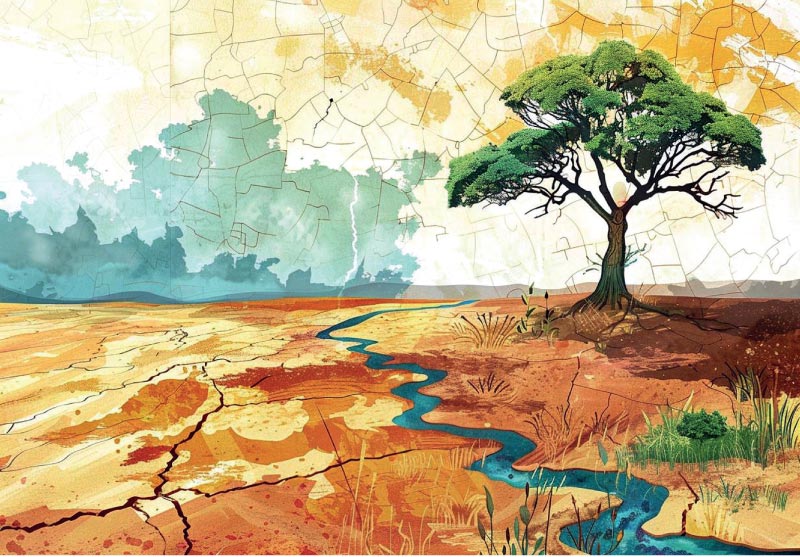

The global challenge of climate change is deeply interconnected with other global crises and issues. Biodiversity and ecosystem loss as well as land degradation due to desertification and drought are all part of the overall “polycrisis” facing humanity in the 21st Century. In particular, vulnerable developing countries such as Sri Lanka are exposed to serious and intertwined threats to critical sectors such as agriculture, tourism, or the coastal zone.

The global challenge of climate change is deeply interconnected with other global crises and issues. Biodiversity and ecosystem loss as well as land degradation due to desertification and drought are all part of the overall “polycrisis” facing humanity in the 21st Century. In particular, vulnerable developing countries such as Sri Lanka are exposed to serious and intertwined threats to critical sectors such as agriculture, tourism, or the coastal zone.

The three “Rio Conventions”—all deriving from the 1992 Earth Summit held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil—aim to protect the world’s climate, biodiversity, and land. They include the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the Convention on Biodiversity (CBD), and the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD). In the last quarter of 2024, all three of these conventions are convening their respective Conferences of the Parties (COPs): CBD COP16 in Colombia in October, UNFCCC COP29 in Azerbaijan in November, and UNCCD COP16 in Saudi Arabia in December.

Collaboration among these Rio Conventions is vital to achieve their respective targets and harness synergies, which occur when actions align with multiple goals and create co-benefits across the areas of climate change mitigation, adaptation, biodiversity conservation, or land degradation neutrality, as well as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) under the Agenda 2030.

Sri Lanka and the three Rio Conventions

On climate change, Sri Lanka has ratified the UNFCCC in 1993 and the Paris Agreement in 2016, with considerable engagement since then. Most recently, Sri Lanka has submitted its updated Nationally Determined Contributions (in 2021) and its Third National Communication (in 2022), and is currently in the process of implementing and reviewing its National Adaptation Plan.

The country has also ratified the Biodiversity Convention in 1994 and adopted its latest National Biodiversity Strategic Action Plan (2016-2022) in 2016. As one of 36 global biodiversity hotspots (together with India’s Western Ghats), Sri Lanka is a key location for biodiversity and has a high level of endemic species of animals as well as plants across its diverse terrestrial and marine ecosystems.

Finally, Sri Lanka ratified UNCCD in September 1998 and submitted its latest country report in 2022, outlining trends in land, cover, productivity, and degradation; access to safe drinking water; drought exposure and vulnerability; carbon stocks; and other relevant metrics.

Linkages and synergies

There are significant linkages and potential synergies between the subject areas and policy processes of all three conventions. For example, Sri Lanka’s climate commitments under the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement identify biodiversity as a key sector and repeatedly refer to land degradation, desertification, and drought across multiple key sectors. Conversely, ecosystem- and nature-based projects can address multiple environmental challenges and provide livelihoods and other benefits to local communities and economic sectors. Restoring degraded ecosystems, such as forests or wetlands, can enhance carbon sequestration and storage, promote biodiversity recovery, provide critical services such as pollination or flood regulation, reduce soil erosion, and improve soil fertility and water availability.

Food systems are another area that cuts across all three Rio Conventions. Sustainable land and water management as well as practices such as agroforestry are critical not only to prevent land degradation and desertification, but also for the conservation of agrobiodiversity, carbon sequestration in soils and biomass, improved soil health and water retention, and long-term agricultural productivity and resilience in the face of climate change. By transforming food systems, the conventions can jointly contribute to food security, climate resilience, and biodiversity conservation.

Science, policy, and means of implementation

Synergies between climate action, biodiversity conservation, and land management extend further than individual actions and projects. Governance, science and knowledge management, reporting, capacity-building, national policy processes, and funding mechanisms all have the potential to work towards multiple goals at once and strengthen overall political momentum and awareness of global environmental crises.

Integrating scientific research into policymaking is essential for the effective implementation of all Rio Conventions and is supported by specialised bodies such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), or the UNCCD Committee on Science and Technology. Each of the three COPs this year will host sessions dedicated to the science-policy interface, highlighting the importance of sharing scientific knowledge and collaborating on research to develop more robust and integrated policies that can simultaneously address multiple environmental issues.

Similarly, means of implementation—encompassing finance, technology, and capacity-building—are crucial for achieving the goals of all three Rio Conventions and play a prominent role in the multilateral negotiations and technical discussions. Coordinating the existing financial mechanisms, such as the Green Climate Fund or the Global Environmental Facility, could help to optimise resource efficiency and ensure that funding is allocated to projects that offer positive synergies and have only minimal negative trade-offs across the areas of climate change, biodiversity, and land management.

In conclusion, 2024 is a key year to maximise synergies between the three Rio Conventions and better address the interconnected polycrisis facing humanity in the 21st Century. By aligning efforts in areas such as climate change mitigation and adaptation, nature-based approaches, food systems, science and policy integration, means of implementation, and high-level political engagement, the conventions can achieve greater environmental benefits and promote sustainable development towards more integrated global environmental governance.

(The writer works as Director: Research and Knowledge Management at SLYCAN Trust, a non-profit think tank based in Sri Lanka. His work focuses on climate change, adaptation, resilience, ecosystem conservation, just transition, human mobility, and a range of related issues. He holds a Master’s degree in Education from the University of Cologne, Germany and is a regular contributor to several international and local media outlets.)