Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Monday, 18 September 2023 00:13 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

While being a victim, the Monetary Board too has been a partner in crime

Failing to inform members of losses due to participating in DDO

Failing to inform members of losses due to participating in DDO

The Monetary Board which has now been disbanded, as the legal custodian of EPF, has issued a statement explaining to its members why it chose to participate in the proposed domestic debt optimisation or DDO by exchanging Treasury bonds to a value of Rs. 2,668 billion for new bonds (see: https://www.cbsl.gov.lk/sites/default/files/cbslweb_documents/press/pr/press

_20230914_participation_of_the_employees_provident_fund_in_the_domestic

_debt_optimisation_programme_e.pdf). The bonds so exchanged had a maturity structure ranging from 2024 to 2045 at coupon interest rates ranging between 6% and 20%.

In terms of the exchange, EPF will get 12 new bonds to a value of about Rs. 222 billion each maturing in each year between 2027 and 2038 at a coupon of 12% till end of 2026 and 9% since then till 2038. Though the principal amount has been protected, the annual cash flow of EPF will be affected by the non-maturity of bonds from 2024 to end-2026 and lower coupon interest income relating to bonds that have higher rates than 12% and 9%. The Monetary Board has omitted – one among many other omissions or commissions in the statement – to inform the members of the losses in interest rates as well as in rupee terms arising from this exchange.

An apology by Monetary Board

In fact, the statement issued is not an explanation but an apology. It says that it had been given only two options by the State – the real custodian of EPF – and the Board has chosen the least costly one ensuring the safety of the principal value of the bonds in the portfolio.

Trying to establish a lie

One option is that if it did not participate in DDO with a minimum threshold value, it will have to pay an annual income tax at the rate of 30% in the future up from the current tax rate of 14%. Strangely, the Board has tried to establish the lie that this 14% tax rate is a concessionary rate. While the Board has not named the other non-concessionary taxpayers in the statement, the previous statements issued on this subject had compared it with the 30% tax paid by financial institutions. There is a commission of error here as I have explained in my previous article on this subject (available at: https://www.ft.lk/columns/The-misunderstood-taxation-of-EPF-and-other-superannuation-funds/4-750423): EPF pays tax at 14% on its gross income including the interest paid to members, while other financial institutions pay at 30% on their net income excluding the interest payments to the suppliers of funds. It is incomprehensible how the Board can call it a concessionary rate when EPF has paid an income tax of Rs. 49 billion in 2022 on its gross income of Rs. 370 billion, when a financial institution earning a similar gross income pays only about Rs. 2 billion as taxes.

Does Monetary Board have two heads?

The other option is to avoid this penal tax rate of 30% and continue to pay at 14% thereby maintaining the principal value of the bond portfolio. This is the best option available to the Board, it says. However, here again, it is the very same Board which recommended to the government that it should impose a penal rate of tax at 30% on those superannuation funds that refuse to participate in the proposed DDO. It seems that the Board has two heads: one head recommends, and the other head accepts without questioning.

To prove its point that it has adopted the best option from the point of EPF members, it has presented the comparative average interest income rates under the two options in the form of a graph for 2024 through 2038. Obviously, the line in the graph pertaining to the option it has chosen lies above the line pertaining to the option rejected. Hence, the Board expresses the satisfaction that it has done the best for the EPF members. There are omissions here and I will present them later in this article.

Real custodian of EPF is the State

As I have mentioned, the Monetary Board is only the legal custodian of EPF. The real custodian in a social security fund of this nature is the State itself. The State is an unseen element, and it conducts its affairs through three visible branches, namely, the Executive, the Legislature, and the Judiciary. These three branches cannot attend to the massive work involved in being a custodian due to lack of knowledge, time, and close involvement. Hence, the State has chosen the Monetary Board of the Central Bank to do the job. However, the State has established the necessary checks and balances to ensure that the Monetary Board does it correctly from the point of the members. Accordingly, EPF accounts are audited by the Auditor General of the Republic, the audited accounts are reviewed by the Committee on Public Accounts or COPA, and finally they are submitted to Parliament for its review.

The Monetary Board should submit its accounts to the Minister of Finance and the Minister of Labour before getting the approval of both ministers to declare the interest paid to members. If there are serious matters pertaining to EPF, the Parliament has powers to appoint select committees to examine them, and the President, the head of the Executive, has powers to appoint special commissions of inquiry to probe into them. Finally, these matters are forwarded to the Judiciary for adjudication. Hence, the real custodian of EPF is the State and it is this real custodian which has offered the two options to the Monetary Board.

Unfulfilled assurance to take EPF out of the Central Bank

In fairness to the Monetary Board, it is doing an unpleasant job which it should not handle in terms of the principal mandate given to it by Parliament. When this proposal was first made to the Monetary Board in 1957, the then Governor Sir Arthur Ranasinghe, as revealed by him in his autobiography, Memories and Musings, had objected to it on this ground. But the Prime Minister S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike had played a smart trick to remove the obstacle. Ranasinghe says that he was offered the post of ambassador to Rome that includes Vatican as well by coaxing his wife, an ardent Roman Catholic, to persuade him to accept it. In the meantime, Bandaranaike had planned with the Deputy Governor D.W. Rajapathirana for the Monetary Board to function as the custodian on the promise that he would be elevated to the vacant position in the bank. That was how EPF got settled in the Central Bank and the Monetary Board became the custodian.

When the Bill was presented to Parliament, ex-Governor N.U. Jayawardena who was a Senator at that time representing Bandaranaike’s party had protested it. His stand was that by establishing EPF in the Central Bank, the new Bank will be reduced to a government department. But according to reports, Bandaranaike had silenced Jayawardena by promising to make a change in the arrangement soon. But as usual, that soon never came and after Bandaranaike’s assassination in 1959, it was completely forgotten. Thus, the fund management of EPF became a permanent job of the Monetary Board.

Failed attempt to establish a social security board

We tried to make a change in this scenario in 2002 under the Central Bank Modernisation Project funded by the World Bank. I headed a committee consisting of all the stakeholders to design a national social security board for Sri Lanka. While the meetings were held in the Central Bank, its office was in the General Treasury thanks to the courtesy of the then Secretary to the Treasury, Charita Ratwatte. Our plan was to amalgamate both EPF and ETF and bring all other numerous pension schemes under the umbrella of the new Social Security Board. With the World Bank’s technical assistance, the draft law was prepared and forwarded to the then Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe.

He readily agreed to enact it in Parliament. If this had happened, EPF would have been shifted out of the Central Bank relieving the Monetary Board of the present unpopular function. But the government that came to power in 2004 decided to scrap the whole project and summarily dismissed the officials attached to the project office. It is now a matter for the new central bank to be setup to initiate work anew to establish a common social security board for Sri Lanka.

Monetary Board: The victim

In fairness to the Monetary Board, it is also a victim through whose throat, the unpopular policy options have been pushed. It is two branches of the State, the Executive, and the Legislature, which have progressively driven Sri Lanka to the present crisis through unsound economic policies – fiscal, external, and growth – throughout the post-independence period. The economy which the British inherited to Sri Lankans at independence was basically a sound one. The country’s foreign reserves were sufficient to finance 17 months of future imports. Public debt was only 18% of GDP, made up of 14% domestic and 4% foreign. The budget was nearly balanced with a deficit of less than 2%. Growth was promising as observed by the visiting World Bank team to the country in 1951. Economic matters changed for the worse since then because of the irresponsible governments that relied on borrowing to finance ever-increasing expenditure programs.

The Monetary Board in its annual reports as well as in the confidential reports submitted to the Minister of Finance before the budget, known as the September 15th Report, warned the Government repeatedly that the country would not be able to continue with these policies. But they were not heeded to and as a result, today, the country has been driven to the present catastrophic state for which the Monetary Board was not directly responsible.

A partner in crime

While being a victim, the Monetary Board too has been a partner in crime. Its statement under reference has not fully disclosed the facts to the members of EPF. First it has given credence to the lie that EPF is subject to a concessionary rate of income tax at 14% compared to the rate of 30% applicable to banks ignoring the differences in the tax base. In fact, in terms of the Bandaranaike-Ilangaratne model under which EPF was setup in 1958, EPF was exempted from both the income tax and the stamp duty. To this date, this exemption remains valid since the original EPF Act has not been amended. It is through the Inland Revenue Act that EPF has been subjected to income tax, first at 10% in 1989 and later at 14% in 2017. Since it pays income tax at its gross income, it is the largest corporate income taxpayer in the country. Bandaranaike-Ilangaratne model did not expect the EPF members to bear this heavy burden.

DDO losses are massive

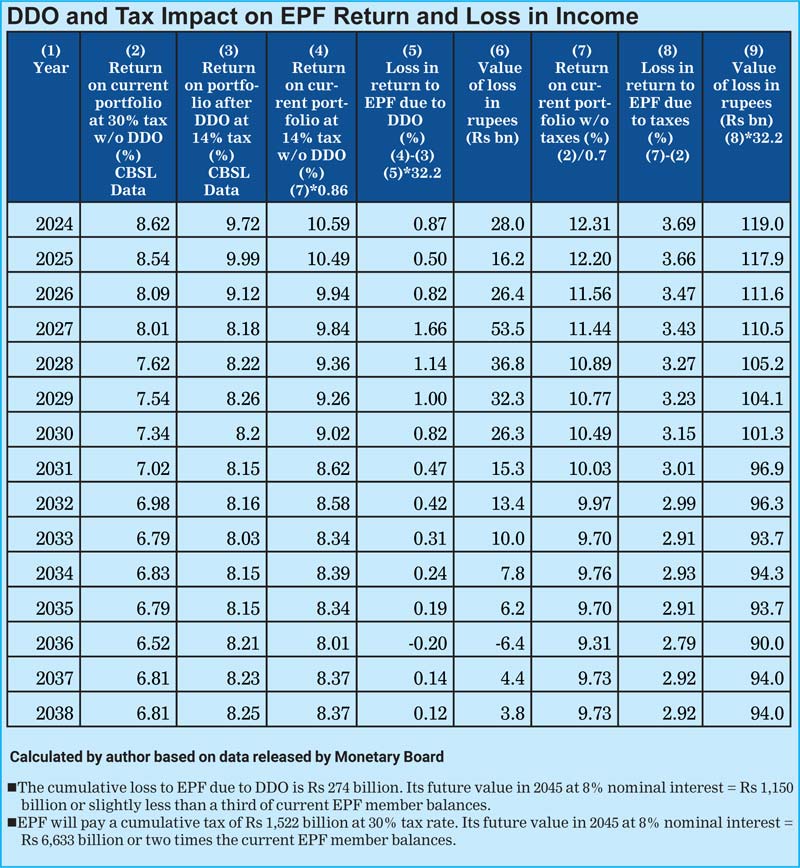

In these circumstances, Table I has presented what the Monetary Board had omitted to disclose to EPF members. Columns 2 and 3 in Table have reproduced what the Monetary Board has disclosed to members in the statement under reference: Column 2 the annual average interest rate EPF would get at a penal tax rate of 30% if it did not participate in DDO and Column 3 the rate which it would get after participating in DDO at the prevailing tax rate of 14%. Suppose there is no DDO, and the tax rate is 14%. The annual average interest rate applicable to current EPF bond portfolio in this scenario is given in Column 4. Column 5 presents the loss in the interest rate and Column 6 its financial value. Column 7 has presented the average interest rate which EPF portfolio will get if it is fully exempted from income tax as provided for by Bandaranaike-Ilangaratne model. Column 8 has presented the loss in the interest rate due to the income tax of 30% and Column 9, its financial value. When these additional calculations are considered, it is clear that the choice made by Monetary Board is not the best option for EPF members.

|

Case for freeing EPF from taxes

These loss incomes in the current portfolio are available for reinvestment. The upper band of the inflation rate which the Central Bank is expected to maintain under its flexible inflation targeting is 6%. If a real interest rate of 2% is added, the desirable discount rate to arrive at the future value is 8%. Using this discount rate to calculate the future value of the lost income due to DDO till 2045 amounts to Rs. 1,150 billion. This is only slightly less than a third of the current EPF member balances amounting to Rs. 3,400 billion. It is therefore equivalent to a tax of 33% which EPF members are paying to the Government by foregoing a part of their annual income.

If EPF is fully exempted from income taxes, the loss in income will generate a future value of Rs. 6,633 billion by 2045. If the Government frees EPF from taxes, the current member balances will grow more than three times to over Rs. 9,000 billion. Hence, the burdens borne by EPF members due to the DDO participation and paying income tax on gross income have been significant contrary to what the Monetary Board maintains as the custodian of EPF.

Full disclosure needed

The full disclosure of facts is a regulatory requirement which the Monetary Board insists on financial institutions under its supervision. It is a customer protection measure. In the statement under reference, the Board has failed to observe this cardinal principle. It has not disclosed to EPF members the losses due to participation in DDO. Given the high tax burden falling on EPF members, it is suggested that the Government should revert to the original Bandaranaike-Ilangaratne model of freeing EPF from income taxes so that members will have a higher cash bundle-more than three times what they will get now – when they retire for old age security. A society that taxes its senior citizens at this rate cannot deliver social justice. Knowingly or unknowingly, two branches of the real custodian of provident funds in Sri Lanka have just done that.

(The writer, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected].)