Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Saturday, 20 May 2023 00:09 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Only history can explain Sri Lanka’s affinity to this far away island in the North Atlantic Ocean; neither geographically nor culturally, are we linked

Only history can explain Sri Lanka’s affinity to this far away island in the North Atlantic Ocean; neither geographically nor culturally, are we linked

- These two months are no different to other months of the year, and the year is no different to every year since independence. A story of a nation on a downward spiral, stupefied and unconcerned

- Seventy years after the British left, that distant era now looks like a mere interlude which ended in 1948. Since then, there has been much hoopla; fuss and bother, a lot of big talk but true greatness has eluded us. We have had, many false prophets, pretenders, empty talkers and plain and simple crooks, but no great men. The situation now seems to be what prevailed before 1815: a weak country ruled by a few families; a country defined by systemic corruption, economic stagnation and overall social decay

Reflecting its status of a burgeoning middle class suburb, the Thalawathugoda supermarket was large and modern looking by Sri Lankan standards. It also provided ample parking, a feature unavailable at most Colombo supermarkets. Wanting to get some groceries I directed my taxi driver in.

Reflecting its status of a burgeoning middle class suburb, the Thalawathugoda supermarket was large and modern looking by Sri Lankan standards. It also provided ample parking, a feature unavailable at most Colombo supermarkets. Wanting to get some groceries I directed my taxi driver in.

The supermarket had no eggs nor fresh milk!

A supermarket which has neither eggs nor fresh milk refutes its very definition (recently I was told at the SLT teleshop down Dickman’s Road that they had no portable telephones). What economic policy led this country to be out of basics like eggs and milk is mind boggling. Unlike the portable phones, these foods are locally produced, in farms, as well as domestically.

Almost from the time of independence, our governments have been talking of promoting both dairy and poultry industries. There are several government institutions specifically assigned for the task. After 70 years of hype, we cannot yet ensure adequate supplies.

Giving up grocery buying I headed home towards Colombo, going past the Japanese built Parliament House. I could not help reflecting on the fact that this impressive edifice was our primary policy maker, directions emanating from there decided the nation’s journey; the country situation today is the sum of the mind-set, attitudes and abilities of our parliamentarians.

Perhaps a metaphor for the country; at high noon the traffic on the Parliament Road is chaotic. Bumper to bumper, crawling forward yard by frustrating yard, progress is measured by the number of times you are able to cut across other vehicles; what would be considered rude in most road cultures, passes for initiative here. To give way to another vehicle was to diminish the meaning of the driver’s private journey, every inch mattered, every second counted.

I was being driven, giving me a fleeting opportunity to observe the other drivers. The shared agony on the Sri Lankan roads appears to have imposed a standardisation even in their appearance; edgy, slovenly men reduced by their own rat like manoeuvres on the road.

The disorder in the country is so pervasive it defies description, to comment on it is trite, like saying there is a lot of water in the ocean. Without grappling with such a generality I thought I will attempt to describe the images of various happenings these two months, impressions they had on me, thoughts that came of them.

The month of April was scorching, a heat wave singed the entire region. Without an electric fan, even the indoors gave no respite. Then a double jeopardy, the cost of electricity was raised substantially at the same time. The relief that the fan gave became exorbitant in price. For a people whose buying power had been already reduced by the drastic depreciation of the rupee, electricity has become a luxury.

In Sri Lanka, adversities do not come singly, hard in the heels of the heat wave, came the torrential monsoons, lashing the fields, flooding the roads; from heat-strokes moving to dengue and malaria warnings overnight.

However, come hell or high water, politics, Sri Lankan style, goes on. May Day which is marked only perfunctorily in most countries now, is still a big event in this country. When an idea is introduced, it seems to assume a permanency in our national psyche, even though the basis of that idea has long ceased to be of any meaning in the originating countries. (look at the deplorable rag of the freshers at our universities, something that does not happen in any other country today!)

Some of our May Day parades carried huge busts of Marx, Engels and Lenin, the former two German Jews, and the latter, a Russian. Those who are uninitiated in such things may wonder why these three fierce looking Westerners are held up as icons at May Day rallies in this very South Asian setting, a multitude so different in character and outlook to them. All three come from mighty nations, hugely productive races and world powers. What German hands manufacture, invariably ends up becoming the standard in that product. Russia, although different to Germany, is no less impressive, for decades the second most powerful country in the world, going eyeball to eyeball with the American colossus.

Marx, Engels and Lenin were of a large mould, men whose life mission was no lesser than to change the course of human history (‘Philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world in various ways, the point however is to change it’ – Marx). They were towering intellectuals, writers with an enormous impact across national borders, inspiring generation after generation. For some reason, for a failed country, for this dispirited nation, these three revolutionaries seem to offer an ideal to look up to, regardless of the gaping dissimilarities between their cultures and ours.

In less than a week after the May Day parades, the nation moved seamlessly towards celebrating Vesak, the most revered event in the Buddhist calendar. Gone were the blood red uniforms of revolution, the battle cry of class war; the devotees made their way to the temples, professing loving kindness towards all beings. Is there a deep-seated confusion or even a bewildering indifference to the moral contradictions that this attempt at reconciling two very different cultures and philosophies represent?

Marxism avowedly is a materialistic philosophy, with no room for religious speculation or constructs. Perhaps such an easy meeting of two disparate philosophies is only possible when the purported believer is either insincere, or, simply incapable of grasping the true meaning of his own contradictory postures.

Socialism does not happen automatically, it is a social order to be constructed consciously, by human will, as well as skill. The Sri Lankans are reiterating their faith in a social construction at which, the Russians and the Germans, despite their best efforts, failed. Brave, or even foolhardy perhaps, does our record since independence give reason for optimism?

If the unfurled red banner of the May Day signifies a march to the unknown, the rituals seen at Vesak celebrations can only portent a long road ahead for the disciple, they are only at the very beginning. Ignorance is the key; the sense of “self” so predominates in their every word and action. Meanwhile, the country is awash with every kind of vice; avarice and can’t hold sway, particularly in the religious institutions.

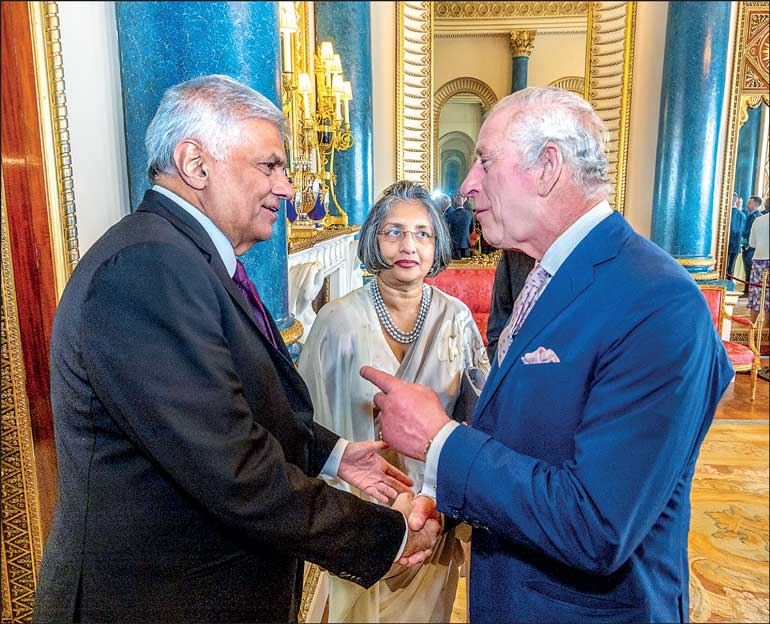

The other image I have of this period is of our President Ranil Wickremesinghe attending the coronation celebrations of King Charles III in London. In September last year, he attended the funeral of Elizabeth II, the King’s mother. In the egalitarian world of today the pomp and ceremony surrounding the royals may look like a circus, however it has worked for the British, one time the most powerful country in the world; and even today, a prosperous democracy whose systems and concepts have come to define good governance.

Under our constitution, the President is to be elected by popular vote, while the position of the king of England is hereditary, a Head of State whose role is primarily ceremonial. Only history can explain Sri Lanka’s affinity to this far away island in the North Atlantic Ocean; neither geographically nor culturally, are we linked.

It makes no sense to quarrel with history, we cannot change it. The British not only conquered the entire island, but also left a permanent imprint on the systems, and even the culture of this country. When we say parliament, elections, political parties, legal systems, Western medicine, the constabulary or even cricket we refer to things that came with them. Not that all of these came in 1815, many were non-existent then even in Britain, while other concepts were in an embryonic stage. But they developed and evolved in Britain, the British were institution builders, that is their genius (compare with our creation – the executive presidency, an institution deplored all around!)

Nevertheless, it was an empire and we were the conquered. If the experience was hurtful for us, it must be deeply rankling for India, much older, larger and populous than Britain. Now, the India story is rapidly changing, with modernity has come wealth and respect. It chose to send its Vice President for the coronation.

Relative to the massive empires they built, the seafaring European nations were small, hard-pressed to find the manpower for the mammoth task of administering their far flung colonies. Conquering was the easy part, in military terms, they were rarely matched; guns versus bow and arrow, professional soldiers versus hereditary leaders. Again and again, they encountered decaying societies, primitive technologies, people led by traditional leaders: conceited, insular and foolish men.

The feudal lords of the native lands may have bamboozled and terrorised their own people, but the moment of truth had arrived; their countries were empty shells, miserably weak. For centuries these comically inept indigenous leaders had vindicated their status with feudal shibboleths. Kept in a state of befuddlement by that system, the people had no capacity to judge their rulers, nor did they have a true assessment of other societies.

These native lords may have been deficient in true capabilities, but they had plenty of pragmatism. Before long, they were playing the role of native administrators of the conquered lands, on behalf of their foreign masters. The shrewd eyes of the colonialists would not have failed to notice the avarice of the local worthies, their supine nature and their greed for office. It suited them well to have these native caricatures running the colonial government, of course, under the watchful eyes of the King’s representative.

I picked these two months (April and May) for no particular reason than that the impressions of this period are still fresh in the mind. These two months are no different to other months of the year, and the year is no different to every year since independence. A story of a nation on a downward spiral, stupefied and unconcerned.

Seventy years after the British left, that distant era now looks like a mere interlude which ended in 1948. Since then, there has been much hoopla; fuss and bother, a lot of big talk but true greatness has eluded us. We have had, many false prophets, pretenders, empty talkers and plain and simple crooks, but no great men. The situation now seems to be what prevailed before 1815: a weak country ruled by a few families; a country defined by systemic corruption, economic stagnation and overall social decay!