Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday, 25 January 2023 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

That we have chosen to destroy our own economy due to some form of wrong interpretation of these restrictions or simply due to a poor understanding of the economic indicators is no one else’s fault than our own

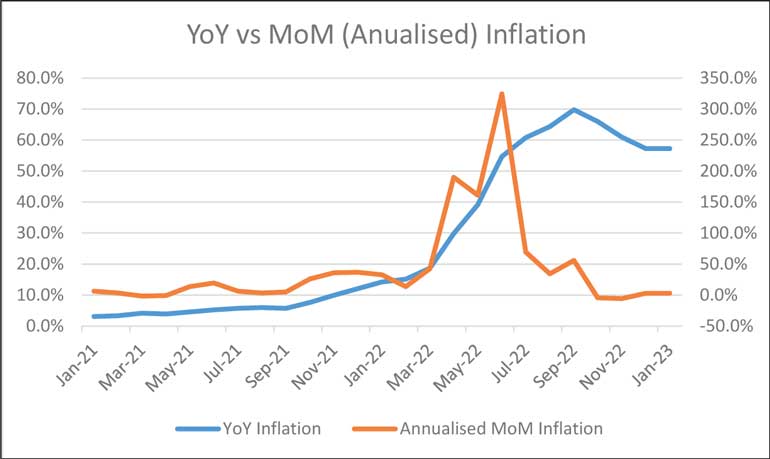

Year on Year vs. Month on Month inflation rates

The Year on Year (YoY) measure of inflation is a very useful tool during normal times working closely with the time scale of annual increments, price revisions, budgeting and even five-year election cycles.

However, when faced with a sudden crisis such as a debt default, the currency crisis or the collapse of agriculture, the YoY figures do not have the precision needed for decision making. The Annualised Month on Month [AMoM] inflation figure based on the same Colombo Consumer Price Index (CCPI) gives a very different picture of inflation in the country.

As shown on the right hand axis, the annualised month on month inflation fluctuated between about 10% and slight negative rates till September 2021. As the different phases of the economic crisis set in, price levels shot up rapidly peaking at 325% in June of 2022 as the currency crashed and shortages set in. The peak of the Year on Year inflation rate is in September at 69.8% several months later. This difference in peaks is entirely the result of a quirk in the mathematical process of averaging out inflation.

The month on month figure highlights two important features of inflation in Sri Lanka. While money printing in general drives inflation, the months between March and July 2022 did not see money printing that could justify the inflation. This period however, was the peak of the currency crisis. In fact the entirety of the figure has remarkable resemblance to the series of specific problems that took place.

These figures also indicate that the worst of the inflation had come to an end by July 2022. By September 2022 price levels had reached an index value of 244.7, up from 144.1, an increase of 69.8% (inflation) on a YoY basis. However, by December 2023 the price index had decreased by 1.5 points to 243.2 at an annualised rate of -2.4%. A situation that appears to reflect general experiences with price levels in this period.

According to the CCPI index prices have been stable for the last three months. Should the price levels continue to remain stable for the next nine months, reported annual inflation will automatically return to single digit number by August 2023 (Price increase from Aug 2022-Aug 2023) as the mathematics of moving averages catches up. Should continued high interest rates create falling price levels, the reported annual inflation rate will reach zero much sooner and then move uncontrollably into negative territory thereafter, bringing with it its own set of serious problems.

The causes of inflation

There can be no doubt that money printing has a direct link to depreciation of the currency as well as inflation. However, Sri Lanka has a long history of money printing and budget deficits going back all the way to our independence. In line with this, the currency gradually depreciated from Rs. 4.77 to the USD in 1950 to the present artificially stabilised Rs. 365 per USD.

It could be said that in 2021 and 2022 the Government resisted the unchecked inflationary pressure of about a decade of money printing, using borrowed funds, till it was forced to let go quite spectacularly. The associated inflation is also therefore a built up one, with a start and an end, as opposed to the much feared hyper-inflationary spiral. Cyclical hyper-inflation can only result from extreme money printing that leads to rapid increases in both prices and income of the general public with rising wages. In the absence of higher incomes, the new higher priced goods would have no buyers, as is the case right now.

In addition, being a poor country, the CCPI is heavily weighted towards food items. The collapse of agriculture, due to the ban on fertiliser, had a direct impact on the prices of these items. Our inability to import cheap food due to the currency crash exacerbated these problems rather than money printing. Had money printing been the primary cause of food price inflation, there would not have been any decrease in food production and people would be consuming more than they used to even at higher prices.

Impact of high interest rates

Traditionally, inflation occurs at the height of an economic boom when everyone has rapidly growing incomes and people are very positive about the future. Rising incomes lead people to demand more and more goods and services, which the industry struggles to supply on short notice, leading to higher prices in what is known as Demand Pull Inflation. Raising interest rates is the easiest and correct solution to this problem as people with surplus funds will keep the money in banks to earn interest while those who have borrowed will pay more in interest reducing demand from all parties.

When applied to food prices, this quite literally means that the national policy is that poor persons should not eat so that food prices will drop through lower consumption. There is no other mechanism to reduce food prices through high interest rates and it may actually reduce food production as farmers are discouraged from farming.

Cost Push Inflation is a second type of inflation that requires different solutions. This is characterised by a reduction in the capacity of production or an increase in cost of production leading to higher price levels. The cost increases of imported goods due to the currency crash and the fertiliser ban leading to low agricultural output are both textbook cases of cost push inflation. High interest rates will reduce this type of inflation only by reducing consumption to match production. The only real solution to cost push inflation is to increase production, revitalise industry including exports and produce import substitutes locally.

The entire world is experiencing cost push inflation right now due to the impact of the Ukraine war. The reactions of other Central Banks have been muted and cautious as compared to that in Sri Lanka.

Real interest rates

Real interest rates can loosely be defined at the actual interest rate in the country minus the inflation rate. It is the goal of central banks the world over to keep real returns as a number close to zero by mirroring interest rates as close to the actual inflation rate in the country as possible. This creates the stability needed in the country to encourage economic growth and development.

Historically, this relationship was well managed, and even during the war, high interest rates were not a particular problem for business as inflation tends to compensate actors for the high interest rates.

In a theoretical environment where interest and inflation rate are both 30% (zero real interest rates) an investor can expect his factory and stock to be worth 30% more in one year, an exporter can expect the currency to depreciate by 30%, in line with the inflation rate parity theory, thus earning him 30% for just holding stock. At the end of the year after paying 30% interest and earning 30% on holding the stock the net gain or loss of stock holding can be reasonably expected to be zero. This can be described as a 0% real interest rate environment in which any exceptional returns can only be gained through hard work and innovation.

The real situation is that while interest rates remain at 30% inflation has come down to 0% on a month on month basis as reported by the Central Bank itself. This means that holding stock would result in a net annual loss of 30% per annum, a figure that cannot be compensated by any reasonable trading profit. It is therefore better to shut down business and stay at home in this environment than to work hard.

This situation would be untenable even for the strongest economies in the world. We are headed towards economic collapse as doing nothing is currently the best course of action in the country, a ludicrous position when the people are starving and malnourished.

The IMF and the solutions

The International Monetary Fund has the primary objective of stabilising and managing the global sovereign debt markets. As such it can be considered a banker and regulator for countries and their creditors. The expectation that the IMF will provide solutions to the country is similar to asking your bank for solutions to your housing loan problem or your leasing company for new ways to earn a living. The only solutions they can give is to say you must cut your costs to below your income, find ways to make more money or sell off assets to settle loans, as the IMF has told us.

There is no reason to believe that the IMF has requested or insisted on high interest rates. Their expectation that the Government must balance their budget is reasonable, however, forcing interest rates up instead of cutting costs is not the desired outcome of that goal. That we have chosen to destroy our own economy due to some form of wrong interpretation of these restrictions or simply due to a poor understanding of the economic indicators is no one else’s fault than our own.

If we are to get out of this mess, we must move to more closely match interest rates to current inflation rates. Given how volatile the monthly inflation rates are at present the Central Bank must also be agile in its setting of interest rates. Should the inflation rate be forced into the negative, we may find ourselves in the same difficult situation that Japan did in the 1990s when interest rates had to be negative.

Under normal conditions few businesses in Sri Lanka have been able to earn more than 10% return. With interest rates at 30% many businesses are making losses and many financial institutions have reduced lending activities preventing many small businesses such as farmers from getting funds. This situation can lead to no good for the country. As income levels fall businesses will see lower turnovers and the Government will get much lower than predicted income from taxes such as VAT. As business profits fall the Government will not see the expected returns from the Income Tax increases, leading to a self-defeating vicious cycle.

The only real way out of this crisis is to get the economy going again. Reducing interest rates to reasonable levels and ensuring those in essential and value adding sectors have access to affordable financing is the most important first step. This must be done immediately to prevent the collapse of the economy.

(The writer holds a CFA, ACA, ACMA, BSc (UK) External.)