Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Tuesday, 4 July 2023 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Gayani Hurulle

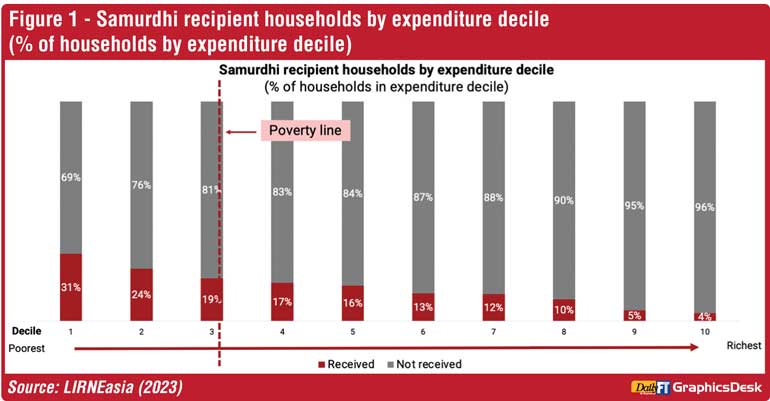

Sri Lanka’s social safety nets have been riddled with multiple challenges. LIRNEasia’s 10,000 sample nationally representative survey showed that the Samurdhi monthly cash transfer program only reached 31% of the poorest 10% of households; meanwhile 4% of the richest 10% of households also received Samurdhi (poorest/richest as defined by household expenditure; Figure 1).

The de jure eligibility criteria for schemes such as Samurdhi have included monthly income or expenditure – which is difficult to verify in many households given the lack of stable paychecks, particularly for groups such as daily wage earners and those in agriculture. This has allowed Samurdhi officials a high degree of discretion when deciding who should, and who should not, be eligible for the monthly cash transfers. As a result, the program was co-opted for political gain.

“I didn’t get Samurdhi until I began working for the ruling political party [at the time]. There was a key person who works with Ministers during elections…. The Samurdhi officer would go to him to see who needs to be given Samurdhi. [He would keep track of those who helped with elections]. Initially, I applied for benefits, but didn’t go for election meetings. I didn’t receive Samurdhi. [Meanwhile, others in the village who went for meetings, did]. I then started going for elections meetings. Then they put me on the Samurdhi list, [and I began receiving benefits].”

Amaraweera (name changed), 49 years, Polonnaruwa

In 2022, the Government announced that it was rolling out its flagship Aswesuma program, finally addressing these longstanding issues.

Providing adequate coverage

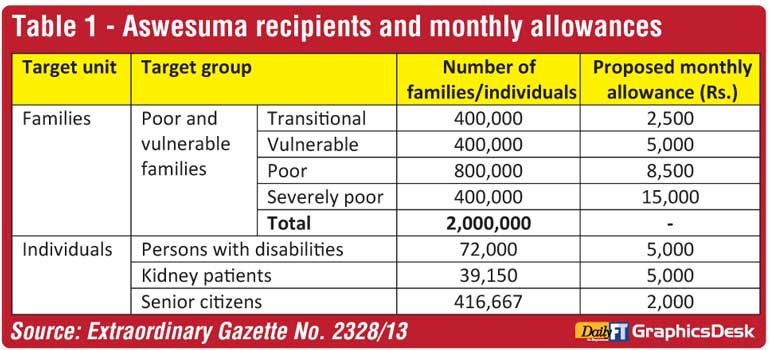

Aswesuma seeks to provide benefits to two million poor and vulnerable families. A defining feature of this program is differential benefits to families based on their level of deprivation – 400,000 families deemed severely poor will receive Rs. 15,000 monthly (a sum unheard of under Samurdhi), while the 800,000 families classified as poor will receive Rs. 8,500 (Table 1).

LIRNEasia’s national survey showed that four million individuals have fallen into poverty since 2019, and that seven million people are living in poverty at present. Some have used this data to indicate that the coverage of the Aswesuma program, which targets two million families, is insufficient. They appear to have confused families with individuals. LIRNEasia’s analysis shows that the seven million people living in poverty belong to two million families – the number of families Aswesuma covers.

Identifying those in need

LIRNEasia’s estimates are based on a unidimensional approach to poverty – the national poverty line defined by the Department of Census and Statistics, which estimates the minimum amount an individual would have to spend each month to fulfil their basic needs. According to this poverty line, last updated in December 2022, an individual spending less than Rs. 13,777 per month would be considered poor. Aswesuma uses a ‘deprivation score’ derived from a formula with 22 different indicators, using a multidimensional approach to poverty. These indicators include (but are not limited to) electricity access and use, vehicle and land ownership, and the number of schoolchildren in a family.

The two million families chosen through the two approaches will differ. A multidimensional approach to poverty, which measures various deprivations faced by the poor in their everyday life, is often thought to be superior to unidimensional income or expenditure-based methods. However, the Government would have to release the ‘deprivation score’ cut-offs used to determine eligibility for the programs, including for the four categories (transitional, vulnerable, poor, and severely poor), to make further inferences on coverage of the Aswesuma program. Further, the relative sensitivity of this approach to sudden shocks such as job losses is yet to be determined.

Verification, appeals, and objections

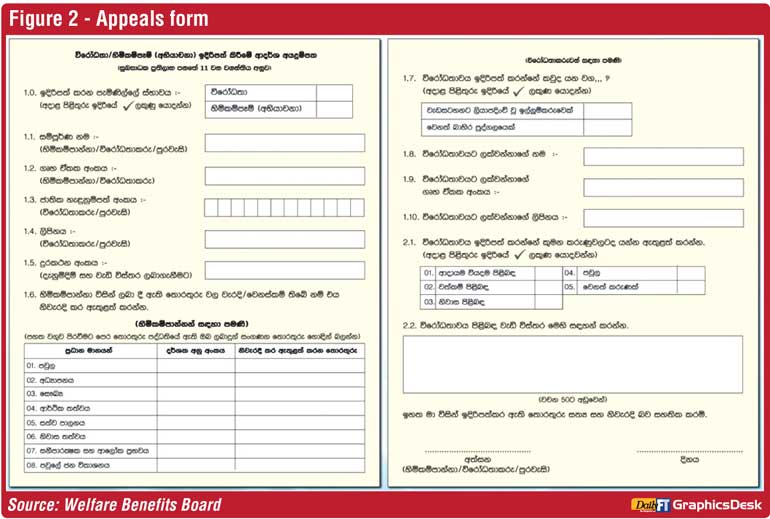

The Government has instituted an appeals and objections process, which the enabling legislation deems crucial in determining beneficiaries. A draft list of beneficiaries was published on 20 June. Those who wish to submit appeals and objections have until 10 July to do so.

The appeals and objections form (Figure 2) indicates that the primary goal of the process is to verify the accuracy of data on the 22 indicators. Verifying the accuracy of data is important, and the use of existing digitalised databases can be explored for this purpose in a purpose-limited and rights-protecting way. For example, inclusion in the Department of Motor Traffic database can be used to verify the accuracy of vehicle ownership, while data from the Ceylon Electricity Board and LECO may be used to verify household definitions and electricity consumption.

Verification being the primary focus of the appeals process implies that the formula-based method can accurately capture those most in need of benefits, including the newly poor made so by sudden income shocks. The use of more objective criteria (away from politically motivated factors) to assess eligibility for social assistance programs should be appreciated. But efforts should be made to permit citizens to make appeals on a more open-ended basis. This data could be used to course-correct, and incrementally improve the social protection landscape through a variety of mechanisms. This could include tweaking selection criteria in the future, increasing funding to the existing program to improve coverage, directing applicants to other programs, and launching new programs.

The Aswesuma program has made many strides in its efforts to create a more evidence based, efficient and transparent social safety net. However, further information sharing and tweaks to the process can help facilitate incremental change in providing access to social protection for more of those in need.

(The writer is a Senior Research Manager at LIRNEasia, leading its research on social safety nets)