Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Thursday, 25 April 2024 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The widespread and ongoing debt crisis today is a wakeup call

By Ahilan Kadirgamar

Sri Lanka defaulted on its external debt for the first time in its postcolonial history in April 2022. The International Monetary Fund (IMF)-led process of recovery that followed has not only been disastrous in terms of the economic policy package proposed by the Government. The underlying analysis of the causes of the debt crisis itself is also flawed. Sri Lanka provides lessons about both the broken global financial system and the widespread consequences of an unjust debt resolution architecture affecting other countries in the Global South.

While debt problems accelerated particularly with the COVID-19 disruptions and the war in Ukraine, the roots of the crisis, different from dominant narratives, go back to the way Sri Lanka was integrated into global capitalism. Sri Lanka’s post-war development policies of financialisation that began after May 2009 coincided with the global financial crisis where great flows of capital from the West flooded countries in the Global South. Sri Lanka’s two IMF agreements in July 2009 and June 2016 encouraged such external borrowings and particularly the floating of International Sovereign Bonds.

Sri Lanka is one of the first countries to restructure its debt in the post-COVID-era. Given its complex creditor profile, it is a test case for the international community and the current global debt restructuring regime. Debt restructuring is fraught with difficulties given the different interests of the multilateral agencies, bilateral donors and commercial lenders. Multilateral agencies are exempted from debt restructuring on the basis of their claimed preferred creditor status, which is being challenged by Sri Lanka’s major bilateral donor, China. Next, there is little coordination between the two major camps of bilateral donors with China on one side and Japan along with India on the other, particularly given their geopolitical rivalry to control Sri Lanka in the Indian Ocean. The commercial lenders, including major investment funds which hold Sri Lanka’s international sovereign bonds, are reluctant even to provide the minimal haircut proposed by the IMF’s Debt Sustainability Analysis (DSA). Instead, they are negotiating hard to gain their pound of flesh.

Creditor-dominated debt restructuring

In debt restructurings, the IMF traditionally plays a leading role. The DSA is the basis for debt relief discussions between the creditors. However, instead of being a neutral arbiter, the IMF programme for Sri Lanka is primarily aimed at protecting the interests of past creditors and future investors: by providing minimal debt relief, ensuring a high level of debt servicing after debt restructuring, and eventually putting Sri Lanka back on the path of commercial borrowing. Indeed, the goal of the four-year IMF programme is to have Sri Lanka floating a US-Dollar 1.5 billion Eurobond, even though the cause of the current debt crisis itself can be traced to the large amount of international capital market loans floated by Sri Lanka.

All this comes at the cost of Sri Lanka remaining economically fragile and susceptible to another default in the event of another shock: the DSA only seeks to reduce Sri Lanka’s total public debt to 95% of GDP – compared with other countries, the level of debt considered sustainable remains extremely high. The IMF’s revenue projections imply that, with the level of assumed debt restructuring, Sri Lanka would still use a third of its revenue for external debt servicing alone in the next years. By way of comparison, the IMF considers an external debt service of between 14% and a maximum of 23% of public revenue to be sustainable for low-income and lower middle-income countries. The IMF itself admits in the DSA that debt restructuring and the IMF programme will not restore debt sustainability, but that debt risks will remain high after debt restructuring.

In view of this scenario, the question arises what the consequences of this creditor-dominated debt restructuring will be for Sri Lanka. The economic, social and political consequences will therefore be discussed in more detail below.

The economic impact

In anticipatory obedience to the IMF and international creditors, the Sri Lankan government imposed austerity measures along with a host of other contractionary measures from early 2022 – one year before the IMF programme was approved. Those measures included the sudden devaluation of the rupee with the rise in inputs for production and essential needs of consumers; the major hikes in interest rates by the Central Bank from 6% to 16.5% resulting in credit becoming unaffordable for small businesses; market pricing of energy leading to the tripling of fuel and electricity prices dampening overall demand in the economy, and the halt of government capital expenditure. All this led to the economy contracting by 7.8% in 2022 and 3.6% in 2023. This unprecedented contraction of Sri Lanka’s economy, possibly the worst since the Great Depression of the 1930s, has led to the collapse of many businesses and loss of formal sector employment. Informal livelihoods were also disrupted: for instance, when kerosene prices quadrupled, fisherfolk had to reduce their trips out to sea and their chances at earning an income were dramatically reduced1.

When the IMF programme came in March 2023, one of the central conditionalities was that Sri Lanka should achieve a primary budget surplus – meaning its revenues should be higher than its expenditure. Already in 2024, Sri Lanka requires a primary budget surplus to meet the IMF benchmark. Achieving a primary budget surplus from a primary budget deficit of 5.7% in 2021 will require government expenditure dwindling to a minimum. After all, it is next to impossible to generate high levels of revenues if the basis for income streams is lost at the same time.

In view of the developments since the 1990s, in which spending and government revenue as a percentage of GDP have been on the decline2, it would be more desirable to focus on increasing revenue in as progressive a manner as possible, instead of cutting spending further. At present, however, the focus is primarily on austerity measures that further reduce the already low public spending3. To the extent that revenue adjustments are being made, this is being done in an extremely regressive manner (see below).

Having to deal with the crisis under the current conditions of austerity gives the elites the opportunity to pursue a more or less hidden agenda of a fire sale of Sri Lanka’s public assets. Privatisation involving external actors would both increase foreign reserves and revenues for the government. The problem is however that in the future, the cost of utilities, fuel and many other public services could become unaffordable for the working people. In the Budget for 2024, sale of strategic lands and privatisation of energy, fuel, transport, banking and telecom infrastructure are being considered. Public companies that are currently running a profit, will be up for sale. This includes Sri Lanka Telecom.

There are plans to lease 300,000 acres of state land for large scale commercial agricultural activities towards export-oriented production at the expense of small-scale farming. A new draft Fisheries Act seeks to allow licenses for foreign fishing vessels and commercialised fisheries more broadly at the expense of local small-scale fishing. Similarly, while the government has decided to capitalise state banks, they are also moving on divesting close to 20% of the shares these banks, raising questions about the future of affordable credit including during times of crisis during which shareholder interests gain prominence.

However, the major public good under threat is electricity: the Ceylon Electricity Board, the main public electricity provider on the island, is first going to be broken into multiple firms for generation, transmission and distribution, and will eventually be privatised. This would in effect reverse decades of progress in ensuring the public have affordable electricity.

In summary, the economic future of generations of Sri Lankans are now being wagered for the interests of powerful external financiers.

The social impact

In this context, the costs of the resolution of the current debt burden are socialised by passing them on to the working people. In strict adherence to the IMF program, the Government raised the goods and services tax from 8% to 18% as the main engine of revenue generation. This is suffocating the working people: such regressive indirect taxation comes after the onetime price hikes with the devaluation of the rupee and market pricing of energy, which has effectively doubled the cost of living while nominal wages have remained stagnant or declined. Another example is energy: as a prior condition to the IMF program, the country is undergoing a bi-annual “cost-recovery pricing mechanism” for electricity.

Several price increases in electricity tariffs until the end of 2023 effectively have led to electricity costs rising by up to 400% for some low-end users4. Customers who are unable to pay the high energy costs will be disconnected from the power grid5. The increased cost of living and deteriorating livelihoods also have an impact on food security and education. Malnutrition is on the rise, as are the number of school drop-outs and youth unemployment6. The situation of single women with dependents, and more broadly the rural and urban poor, are terrifying because little will change in their living conditions in the foreseeable future.

The IMF program also has a benchmark for how much a social safety net should cost for people affected by the impact of the austerity measures. This value shows the IMF’s true priorities: while it sets aside (maximum) 4.5% of GDP per year for foreign currency debt servicing, only a mere 0.6% of GDP is to be provided for the social safety net through targeted cash transfers7 – and this in a context, where poverty levels have doubled. While the 0.6% does not vary much from historically observed expenditure on cash transfers, needs have risen sharply due to the endangered livelihoods of a large part of the population as a result of the aforementioned regressive taxes, price hikes, etc.

At the same time, spending on universal social services remain underfunded, seen for instance in fee levying in higher education or patients having to purchase their medicines when they go to government clinics. For a country that by the 1970s boasted high Human Development Indicators (HDIs) mainly thanks to its robust social welfare policies of free education, universal healthcare and a widespread food subsidy programme built up since the 1940s, the current policy package is a further direct attack on the welfare state. Gradually, targeted social protection measures are to replace universal provision8.

This is all the more dramatic given that in an economy where close to two thirds of the country’s population belong to the informal sector, it is almost impossible to target social protection to predefined recipients. As the livelihoods of many people are seasonal, agriculture, for example, may be affected by a crisis at one time and fishing in another region at a different time. By restricting the groups of recipients, people who do not belong to the defined group fall out of the social safety net. The rationale behind implementing these targeted social protection measures seems to be the long-standing neoliberal agenda to abolish universal social benefits for which Sri Lanka was one of the last bastions.

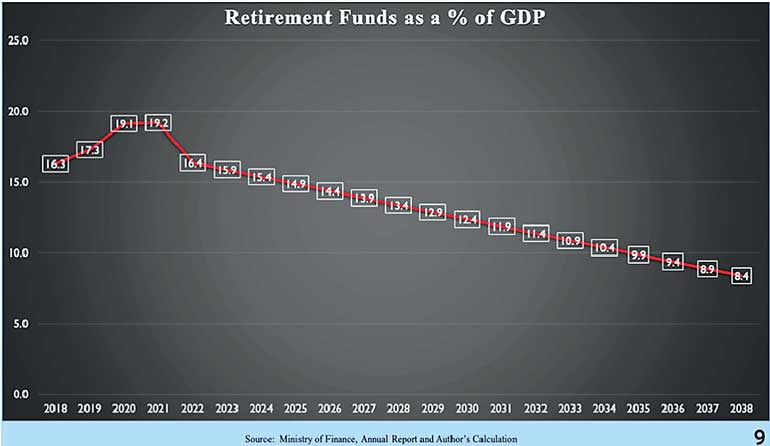

Workers in the formal sector – including women in the garment industry and tea pluckers that earn wages below the poverty line – are obliged in Sri Lanka to pay into pension funds to save for their retirement. This group was hit by an additional channel: international bondholders made a domestic debt restructuring (DDR) a condition for further negotiations, although the crisis was not a domestic debt crisis, but a purely external debt crisis. The IMF congratulated Sri Lanka about the DDR. However, the DDR will result in these retirement funds losing 47% of their value, while financial institutions and wealthy investors in local bonds have been left scot-free. The way in which the domestic debt restructuring was carried out – even prior to external debt restructuring and solely focusing on retirement funds – is illustrative of the broader approach to debt resolution: namely to shift most of the burden onto working people.

Exploitation and social exclusion coupled with brutal state repression are the means by which the debt crisis is being resolved at the social level in Sri Lanka. This is particularly evident in the way the government deals with the plight of economically marginalised people: since December 2023 the Government focuses on a new war on drugs and petty crimes. This however does not mean focusing on solving public health and social issues, but repression in the form of unauthorised searches and arbitrary arrests, with over forty thousand people having been arrested and human rights organisations voicing concerns over grave human rights violations10.

The political impact

Politically, the current crisis is characterised above all by a worrying increase in authoritarian repression. Despite surviving the civil war, Sri Lanka’s electoral democracy now faces a serious challenge with authoritarian measures including the postponement of local government elections claiming lack of funds for elections.

Sri Lanka’s current Parliament lacks legitimacy after the great revolt threw out the last president Gotabaya Rajapaksa in 2022. At the head of the government is now a president, Ranil Wickremesinghe, who was not elected by the people, but by a parliament in which the people have little faith11. Moreover, as mentioned in the national Budget for 2024, the Government seeks to enact or amend sixty new laws, with this illegitimate parliament, even as elections are due in autumn 2024. Many of these new laws, including for fiscal management, central banking, commercial banks, utilities, public private partnerships, are part of the “structural benchmarks” of the IMF program. These are furthermore supported by the World Bank, who is involved in development and implementation.

Scores of other laws and amendments proposed by the Government relate to anti-terrorism, curbing freedom such as of free speech, privatising higher education, dispossessing fisheries livelihoods, etc. For instance, the draft bill on anti-terrorism foresees a very broad definition of “terrorism” and gives heavy powers to senior police officers to detain people. The draft of the “Online Safety Bill” plans to set up an Online Safety Commission and very vaguely and overbroadly formulates the wording of conduct designated as punishable offences12. This will restrict the democratic space to both resist authoritarianism and demand economic justice including of trade unions, student organisations and other social movements. While the IMF programme sets the conditions for economic policies, the Government is focused on repression necessary to attack resistance against the above-mentioned economic policies.

Furthermore, all these laws are being rushed through a parliament that is likely to be washed out in the elections. This agenda of railroading through a neoliberal and repressive legal regime is likely to create constitutional crises in the years ahead as governments with new mandates are voted into power.

Such undemocratic measures are also linked to ethnic and religious polarisation, which the Government and other nationalist forces are using to distract attention from the economic crisis. In light of Sri Lanka’s long and troubled past of ethnic polarisation, it is to be feared that minorities will once again be made scapegoats for the current grievances and that fascist tendencies will gain strength. However, Sri Lanka has a long democratic tradition as the first country to gain universal suffrage in Asia without even a single successful military coup. In this context, the unprecedented debt crisis is again testing the democratic body politic. Its survival now depends on whether social institutions such as trade unions and civil movements manage to enforce the protection of rights and freedoms, even if the country faces major political upheavals in the years ahead.

International implications

Sri Lanka, for better or worse, has been a harbinger of political economic changes in the Global South. It was the first country in Asia to gain universal suffrage and mature into an electoral democracy. It was also one of the early welfare states in the developing world achieving significant advances in HDIs. However, it was also the first country in South Asia to go through liberalisation with the Structural Adjustment Programs of the IMF and World Bank in the late 1970s. In this context, it is again considered the canary in the coalmine of the debt crisis today.

The current economic experimentation in Sri Lanka with the IMF programme and debt restructuring is already devastating its working people and provides lessons for other countries on the brink of external debt default in the Global South. Indeed, Sri Lanka’s escalation of debt problems with commercial borrowings in the international capital markets and its prolonged crisis and inability to resolve this crisis reflect a broken global financial system.

restructure its debt, there are already investments coming from China and India, as they try to stake their claim in Sri Lanka with a view towards grabbing strategic assets such as ports, power generation, fuel supply and financial businesses. Such geopolitical moves can have an excessive influence on the debt restructuring process adding further challenges to debt resolution. Lessons from Sri Lanka’s own past, as with many such postcolonial countries, do not bode well for a history where economic problems and geopolitical tension led to not just the emergence of authoritarian regimes, but also proxy wars that tore apart societies.

Concluding questions

At the heart of the predicament of Sri Lanka’s debt crisis are questions about the future of development financing and a fair solution to debt problems.

It can be argued that if Sri Lanka did not follow the path prescribed by the IMF, and instead took a more forceful stance towards its external creditors, it may have achieved more in terms of debt relief. After all, there was hardly any significant bridging finance after the default from the donors as claimed by the proponents of the IMF programme. Instead, Sri Lanka’s import bill continues to be largely financed by its own foreign revenues. A paper on Sri Lanka’s debt crisis13 argues that progressive international precedents of debt forgiveness should be looked to in order to address this crisis. The authors refer to the elimination of close to half of West Germany’s massive debt overhang with the far-reaching London Debt Agreement of 1953, which, because of unprecedented elements in the agreement, created the fundamentals for economic growth, public investment and social spending. The London Debt Agreement has set the precedent for prioritising a country’s future economic prospects, not the creditors’ interests of maximum profit at the expense of the economic, social and political fabric of the country. Sri Lanka’s debt resolution and economic future may also set international precedents – for better or worse.

When it comes to the roots of the crisis, commercial borrowing for development promoted for countries like Sri Lanka has only pushed them into unsustainable debt. What then are the alternative sources of external development financing? This is going to be the major question as the crisis-prone architecture of international finance is redesigned to provide sustainable development financing for the Global South.

Next, the role of the IMF as an “arbiter” in debt restructuring should also be questioned. The IMF has proven to be resistant to change and only seems to aggravate crises as in the case of Sri Lanka. Instead of the IMF, the United Nations could take over the task and mediate in debt restructuring. This would also address the contradiction and conflict of interest of the IMF as both a lender and an arbiter of debt restructuring.

Finally, the question arises as to how development financing can be structured in such a way that countries retain sufficient autonomy to drive development in the interests of their own citizenry. From the case of Sri Lanka, it is becoming increasingly clear that it is necessary to create room for industrial policies particularly for the local markets and to consider policies of self-sufficiency in food and essentials where possible to weather external shocks without sacrificing the basic needs of its people.

The widespread and ongoing debt crisis today is a wakeup call – not just for the people in Sri Lanka who are struggling to survive amidst the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. But also for the international community to finally and fundamentally rethink the international financial system that was created in the aftermath of the Great Depression.

Footnotes:

1Reuter (08/09/2022): “No kerosene, no food, Sri Lanka’s fishermen say“, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/no-kerosene-no-food-sri-lankas-fishermen-say-2022-09-07/

2On the development of revenue and expenditure, see Central Bank of Sri Lanka: “Summary of Government Fiscal Operations (1990 to the Latest)”, https://www.cbsl.gov.lk/en/statistics/statistical-tables/fiscal-sector.

3See Daily FT (28.11.2023): “Budget 2024 and the working people”, https://www.ft.lk/opinion/Budget-2024-and-the-working-people/14-755657

4Calculation by the author and his team based on fees between September 2022 and September 2023.

5See The Sunday Times (12.11.2023): “CEB disconnects electricity to over 500,000 defaulters”, https://www.sundaytimes.lk/231112/news/ceb-disconnects-electricity-to-over-500000-defaulters-538338.html

6See UNDP (2023): „Understanding Multidimensional Vulnerabilities: Impact on People of Sri Lanka A Policy Report Based on the Multidimensional Vulnerability Index derived from UNDP’s National Citizen Survey 2022-2023”, https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2023-10/undp_multidimensional_vulnerability_report_sri_lanka.pdf and UNICEF (2023): “Sri Lanka Economic Crisis 2023 Situation Report No. 1”, https://www.unicef.org/media/143836/file/Sri-Lanka-Humanitarian-SitRep-No.1-(Wirtschaftskrise),-Januar-bis-Juni-2023.pdf

7The target cash transfer assistance relates to programmes in support of selected low-income households, elderly people, disabled people and people with chronic kidney disease.

8See a detailed account in: Kadirgamar, N.; Feminist Collective for Economic Justice: “Targeting Social Assistance in the context of crises and austerity: the case of Sri Lanka”, Expert Paper UN Women and International Labour Organization, EGM/WS2024/EP.8.

9Ministry of Finance Sri Lanka, Annual Report, 2023.

10See Reuters (18.01.2024): „Sri Lanka to continue drug crackdown despite rights group concerns – minister“, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/sri-lanka-continue-drug-crackdown-despite-rights-group-concerns-minister-2024-01-18/.

11On the question of the effects of a lack of legitimacy despite legality, see Daily Mirror (01.08.2022): “Abyss between Legality and Legitimacy“, https://www.dailymirror.lk/opinion/Abyss-between-Legality-and-Legitimacy/231-242136

12See for more assessment: ICJ (29.09.2023): „Sri Lanka: Proposed Online Safety Bill would be an assault on freedom of expression, opinion, and information“, https://www.icj.org/sri-lanka-proposed-online-safety-bill-would-be-an-assault-on-freedom-of-expression-opinion-and-information/

13See Chandrasekhar C. P,, J. Ghosh and D. Das (2023): “Paying with Austerity: The Debt Crisis and Restructuring in Sri Lanka”, Working Paper, https://peri.umass.edu/publication/item/1776-paying-with-austerity-the-debt-crisis-and-restructuring-in-sri-lanka

(The article was originally composed in English. The author benefited from research assistance by Shafiya Rafaithu, Yathursha Ulakentheran, Madhulika Gunawardena and Sinthu Srihtaran in writing this article.)

(Courtesy – Global Sovereign Debt Monitor)