Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday Feb 13, 2026

Wednesday, 16 December 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

It is desirable for the new Government and the legislators elected recently to consider amending the Assistance to and Protection of Victims of Crime and Witnesses Act No. 4 of 2015

On 7 March 2015, a new law came into effect in Sri Lanka by the name of Assistance to and Protection of Victims of Crime and Witnesses Act No. 4 of 2015 (APACW Act). It was not a law fostered or  generated inside the country, but rather an adoption to fulfil international commitments in line with the developments of human rights internationally.

generated inside the country, but rather an adoption to fulfil international commitments in line with the developments of human rights internationally.

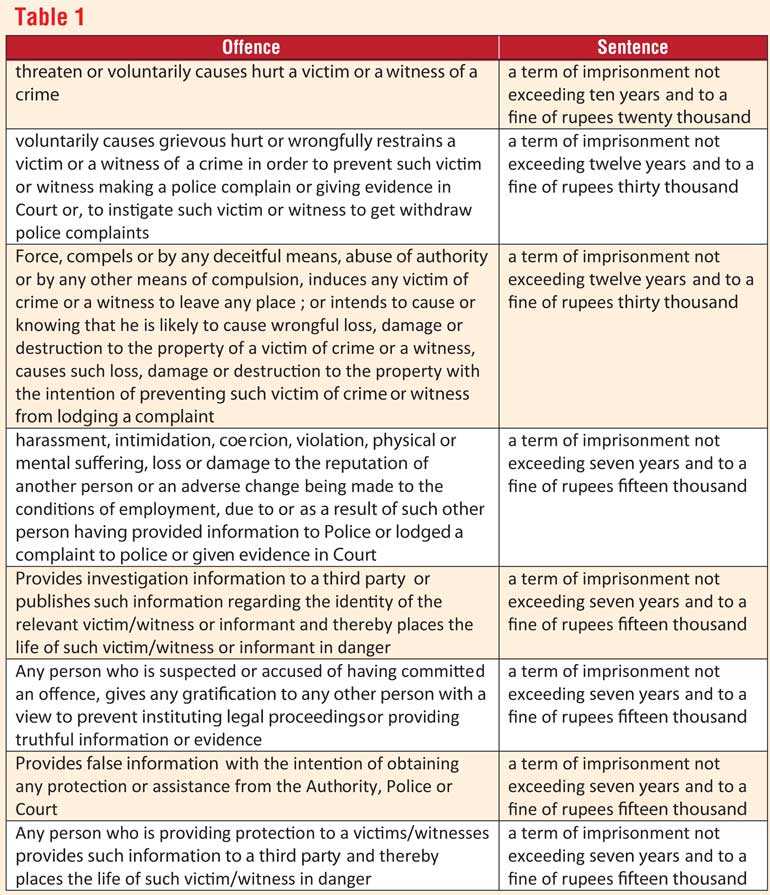

Assistance to and Protection of Victims of Crime and Witnesses Act No. 4 of 2015 created a new institution called National Authority for the Protection of Victims of Crime and Witnesses and the Act introduced new offences to our legal system by section 8, as seen in table 1.

An attempt to commit any of the aforesaid offences also is an offence as per section 9 of the Act and carries the same sentence provided for the original offence.

The APACW Act gave powers to the police to arrest any person for the abovementioned offences even without an arrest warrant from Court.

Once arrested, the Magistrate’s Court or even the High Court does not have power to grant bail to suspects under this Act and it is only the Court of Appeal has to power to grant bail, that again only under special circumstances. In other words, those who are arrested under this Act shall be kept in remand until the conclusion of trial, unless there is a special reason to satisfy the Court of Appeal.

Section 10 (1) of the APACW Act provides that “no person suspected, accused or convicted of such and offence shall be enlarged on bail, unless under exceptional circumstances by the Court of Appeal”.

Hence, if you were arrested under this Act even in an area far away from Colombo, you have to file the bail application only at the Court of Appeal at Colombo. And that again, only if you could afford the cost.

In our criminal justice system, generally, suspects are not expected to incarcerate until the conclusion of trial, which is in line with the concept of “presumption of innocent until proved guilty” embedded in our Constitution as well. On the other hand, statistics reveals that it take an average of 10 years to conclude a trial in the High Court.

For most of the offences, the Magistrate’s Court has power to grant bail and in few serious offences the bail has to be obtained from the High Court of the relevant province. However, there are few special laws created for special crimes preventing bail until the conclusion of the case.

Under the Antiquities Ordinance bail has been completely shut off. Section 15 C (as amended by Act No. 24 of 1998) provides as follows: “Notwithstanding anything to the contrary in the Code of Criminal Procedure Act, No. 15 of 1979 or any other written law, no person charged with, or accused of an offence under this Ordinance shall be released on bail.”

Therefore, those arrested for archaeological related offences under the Antiquities Ordinance have two options, i.e., to defend his innocence facing the trial or plead guilty and have a sentence of a fine and a suspended prison term (i.e. without actually serving a prison term). In almost all cases, the accused prefer latter. In rarest case, Court of Appeal has intervened for bail after a prolong incarceration, as in the case of CA/MC/RV /01/ 2016(Bail) when the Attorney General not objected for granting bail.

Similarly, under the Prevention of Terrorism Act section 7, the suspects or accused are being remanded until the conclusion of trial or the Attorney General decides otherwise.

Since 1997, from the enactment of Bail Act No. 30 of 1997, as per section 2 of the said Act, granting bail became the rule and the refusal of bail became the exception. The Bail Act does not apply to other special enactments which have provided restrictions for bail such as the aforesaid Antiquities Ordinance, Prevention of Terrorism Act and similar legislations such as Public Security Ordinance, Immigration and Emigration Act, Public Property Act No. 12 of 1982, Poisons, Opium, and Dangerous Drugs Ordinance and lastly the APACW Act.

In the past bail for the offences under Offensive Weapons Act No.18 of 1966 has to be obtained from  the Court of Appeal. Section 10 of the said Act was amended by Act No.2 of 2011 by which High Court was given powers to grant bail for offences under the Offensive Weapons Act since year 2011.

the Court of Appeal. Section 10 of the said Act was amended by Act No.2 of 2011 by which High Court was given powers to grant bail for offences under the Offensive Weapons Act since year 2011.

Hence, as at today, for all the major offences such as murder, large quantity of drug related offences, fire arm and explosive related offence, the High Court of the respective Province has power to grant bail. There are High Courts in every district and in some cases more than one location (for example for the Gampaha District, there are two High Courts at Negombo and Gampaha). With regard APACW Act, the High Court does not have power to grant bail, but everyone has to come to the Court of Appeal, although the offences under APACW Act would be tried before the High Court.

There is no proper record as to how many cases reported to Courts by the police under APACW Act for the last year or for this year so far. Unconfirmed sources say that there are 27 cases have been assisted for the year 2019 by the special police division established for the investigations and protections under this Act. But as of the first week of September 2020, there were 35 bail applications had been filed in the Court of Appeal for this year under the APACW Act.

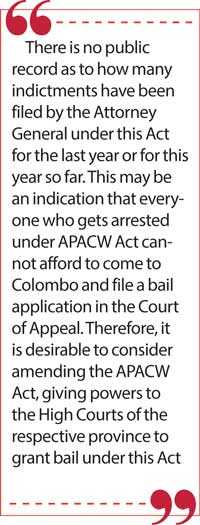

There is no public record as to how many indictments have been filed by the Attorney General under this Act for the last year or for this year so far. This may be an indication that everyone who gets arrested under APACW Act cannot afford to come to Colombo and file a bail application in the Court of Appeal. Therefore, it is desirable to consider amending the APACW Act, giving powers to the High Courts of the respective province to grant bail under this Act.

The other major issue is that there is no vetting process or scrutiny before arresting a suspect and produce before Court under the APACW Act. For certain offences under the Penal Code, Police need to obtain sanction from the Attorney General, as provided in section 135 of the Code of Criminal Procedure Act. But, under the APACW Act, it is the OIC of the police station that decide whether to report facts under this Act or not. The moment, police product a suspect under this Act, the Magistrate has no power to release him on bail.

Under the Public Property Act, if a suspect produce to Court with regard to an office in which the value of the property is more than Rs. 25,000, a certificate need to file to Court from a Police officer not below the rank of Assistant Superintendent of Police (ASP). Thereby, the legislator has provided some scrutiny by a higher rank officer, before deciding to produce a suspect under the Public Property Act. Because, for offences under Public Property Act where the value is over Rs. 25,000, the bail Act does not apply and the suspect need to show exceptional circumstances to obtain bail.

Likewise, an amendment is deserve to be made to the Public Property Act, making mandatory to obtain sanction from the ASP of the area or some high rank officer of Police, before producing a suspect to Court under this Act. In the case of CA Bail 40/2019, the Court of Appeal decided to grant bail for the suspect, after observing, among other things, that the accused had merely caused to send two letters demand though his lawyer, to two witnesses.

In the circumstances, it is desirable for the new Government and the legislators elected recently, to consider amending the Assistance to and Protection of Victims of Crime and Witnesses Act No. 4 of 2015 in these aspects and thereby allow the High Court in each province to decide bail under this Act rather than the Court of Appeal and also to provide a supervision by a higher ranked officer of the Police Department before producing suspects under this Act to the Court. These amendments, if introduce, will not harm the purpose of the Act and make justice closer and reasonable to people.

(The writer is an Attorney-at-Law.)