Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Saturday, 6 July 2024 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sri Lanka is considered a hotspot for climate change impacts. Over the past 20 years, the country has experienced frequent natural disasters, predominantly floods and droughts. According to the Climate Risk Index 2021, which measures a country’s exposure and vulnerability to extreme weather events, Sri Lanka ranks 30th out of 180 countries in terms of vulnerability.

Sri Lanka is considered a hotspot for climate change impacts. Over the past 20 years, the country has experienced frequent natural disasters, predominantly floods and droughts. According to the Climate Risk Index 2021, which measures a country’s exposure and vulnerability to extreme weather events, Sri Lanka ranks 30th out of 180 countries in terms of vulnerability.

“On average, Sri Lanka experiences LKR 50 billion (US$313 million) in annual disaster losses related to housing, infrastructure, agriculture, and relief. Most of this figure—LKR 32 billion (US$200 million)—is accounted for by losses from floods. Cyclones or high winds account for LKR 11 billion (US$68 million), with droughts and landslides accounting for LKR 5.2 billion (US$32 million) and LKR 1.8 billion (US$11 million) respectively. This is equivalent to 0.4 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) or 2.1 percent of government expenditure.” (Source: Contingent Liabilities from Natural Disasters, Sri Lanka published by Disaster Risk Financing and Insurance Program, World Bank Group)

Thus, natural disasters, particularly floods and droughts, have become a critical burden on Sri Lanka’s economy. While natural disasters cannot be entirely prevented, they can be mitigated. Regrettably, the floods, droughts, landslides, and earth slips we are experiencing today are mostly attributable to human interventions.

There are historical records of natural disasters before the colonial interventions in Sri Lanka; however, such disasters were rare. Ancient Sri Lanka’s land-use system and associated human settlement development were sustainable. Central hills were conserved which could hold heavy precipitations received from monsoons in their thick tree canopies and strong spongy topsoil layer. It released the stored water gradually to streams and rivers making most of the nation’s rivers perennial. The water also carried adequate nutrients for paddy cultivation in the dry zone.

Economic development and associated large-scale human settlements, and cities were concentrated in the dry zone. The globally renowned Sri Lanka’s “hydraulic civilisation” was built on this principle. Although settlements existed in the wet zone, they were developed in harmony with nature (i.e. upcountry garden land use system), which maintained the retention of continuous tree canopies and developed the topsoil layer.

Economic development and associated large-scale human settlements, and cities were concentrated in the dry zone. The globally renowned Sri Lanka’s “hydraulic civilisation” was built on this principle. Although settlements existed in the wet zone, they were developed in harmony with nature (i.e. upcountry garden land use system), which maintained the retention of continuous tree canopies and developed the topsoil layer.

Although repeated invasions from South India caused the Sinhalese settlements in the Dry Zone to move towards the hill country, the sustainable land use system of Sri Lanka was irrecoverably destroyed by the British colonial intervention, through:

The ultimate results that we are facing today are:

The situation has become alarming due to climate change-related impacts. Scientists have concluded the climate change-related impacts on Sri Lanka as:

We have several public sector institutions, directly and indirectly involved in natural disaster management activities. However, their activities have been largely limited to predictions of climate-related disasters and once a disaster occurs recovery activities.

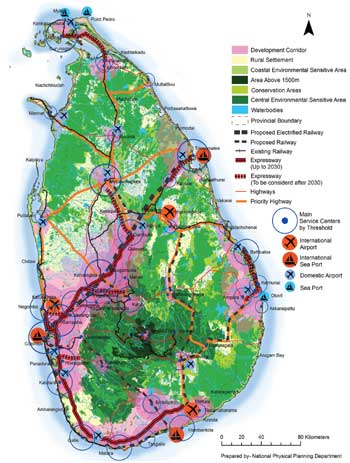

In 2011, the National Physical Planning Department prepared the “National Physical Plan” for the whole country, which focused on conserving environmentally sensitive areas, primarily the central hills and coastal belt, and concentrating developments in specific dry zone areas. Four out of five large development zones were in the Dry Zone. The plan was approved the same year and has been amended twice, in 2019 and 2023. The amended plans also agree on the need to conserve these environmentally sensitive areas as a key solution for disaster mitigation at the macro level. However, despite these proposals, there have been limited efforts to implement long-term sustainable solutions for disaster mitigation.

Large teams of local experts from all the relevant fields were involved in drafting the National Physical Plan and its subsequent revisions.

Although countries that are least responsible for climate change like Sri Lanka are the worst affected; we are compelled to face the consequences. Thus, orienting all potential resources to strengthen the rainwater retention capacity of the wet zone, particularly the central hills (through reforestation and storing in reservoirs) and trans basin diversion of captured and stored water from the wet zone to the dry zone is a valid macro level intervention that could address both floods in the low reaches and the droughts, especially in the North Central, Eastern, and Northern provinces.

Engineer Dr. P.A.K. Karunananda, Editor of ‘ENGINEER’, the journal of the Institute of Engineers, stated in an article that “approximately 100 MCM of water can be redirected from Kehelgamu Oya, a major upstream tributary of the Kelani River to the Mahaweli River. Additionally, around 75 MCM of water from the Norton Bridge reservoir could be transferred during low-flow seasons. It is also possible to transfer about 175 MCM annually by constructing a 6 km-long tunnel. Moreover, the Mahaweli River basin needs to have the capacity to store this amount of water in its system. A project aiming to raise the Kotmale dam and construct a few dams in the upper catchment area has been proposed to facilitate this.”

Thus, it would be a program similar in scale to the Mahaweli Development Program. Key initial steps of such a program would include:

The program will consist of several large and medium-sized projects spanning the whole country. These projects include reforestation; construction of stormwater retention reservoirs; diversion of water from the Kelani River to the Mahaweli River; augmentation of water retention capacities of existing reservoirs and construction of water distribution systems; regeneration of tea plantations integrating soil conservation and water retention capacities; development of new settlements; and the associated infrastructure. One of the issues with the investment of multinational donor funds in Sri Lanka is the dispersion of financial resources among numerous uncoordinated small projects, rather than focusing on national economic growth. Thus, it is an opportunity to focus all the available and expected multinational financial resources on the trans basin stormwater diversion project from the wet zone to the dry zone which can also be oriented as the primary program for economic crisis recovery. Such investment is multifaceted and primarily addresses natural disaster mitigation and food production through integrated water resources management. It will also reduce the annual disaster losses, estimated to be approximately Rs. 50 billion.

The most significant aspect of this kind of program is that it can involve all the key national institutions involved – the Ministry of Irrigation and Water Resources, the Ministry of Agriculture, the Mahaweli Development Authority, the Urban Development Authority, the Ministry of Local Government and Local Authorities, Export Development Authority, etc.

The construction industry is vital in creating jobs and driving economic development. Its impact extends beyond providing employment and influences various aspects of society, contributing to the prosperity of local economies. The construction industry in Sri Lanka contributes about 9% to the GDP, employing about 600,000 people (Source: “Construction Industry in a Crisis” Daily FT, written by Eng. Col. Nissanka N. Wijeratne, CEO, Chamber of Construction Industry, Sri Lanka). The trans-basin water diversion program has the potential to transform the currently stagnant construction industry into a vibrant economic activity; thus generating a significant number of employment opportunities across the country; and creating a positive impact on economic crisis recovery.

Effective flood and drought mitigation strategies are developed at three levels – macro, local, and micro. However, this article focuses solely on the macro-level perspective.

(The writer holds a FITPSL, HFPIA. He can be reached at [email protected].)