Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Thursday, 11 June 2020 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

In the first few days, as America burned, the world looked on amazed and bewildered, wondering what this would mean for the immediate and long-term future.

As the protests settled down and drew larger crowds with an overwhelming number of young people, one began to think of other movements in Hong Kong, in India, with regard to climate change, the Me Too movement where young people battled police and began to insist on a world based on principles.

There was damage, there was destruction but there was also hope. For a moment then one glimpsed what it would be like in an era beyond the “strongman”.

Strongman theory and authoritarian governance

For the past decade, the theory of the strongman has captured the imagination of elites as well as the common man in western and eastern societies. In the United States, in the alt right movements in Europe, in Asia, and Latin America this narrative was fast becoming the legitimate narrative.

Born out of an era of terrorism, rampant corruption and East Asian models of leadership, the strongman theory pointed to the need for authoritarian forms of governance. In some countries this authoritarianism was combined with populism to create a volatile and heady mix of emotions.

Authoritarian governance made the public believe that being authoritarian made them effective and efficient even though this may not always have been the case. In some countries the corruption and the chaos of eras of democratic governance made their appeal even greater. Public servants and politicians became the new enemy as authoritarian leaders questioned legitimate process as causing delay and called out for quick, even if arbitrary, forms of decision making.

When in power they excelled in the use of the criminal justice system to bring charges against media, intellectuals and political opponents so as to silence them effectively. This combined with impunity for law enforcers, an omnipresent surveillance system and a cowed judiciary ensured that political will would have no resistance.

Populism was often the handmaiden of authoritarian government and political parties in the last decade. Leaders were busy mobilising majority opinion against ethnic and religious minorities, dissident intellectuals, journalists and political opponents. They excelled in mobilising your neighbour against you so that fear ran deep and one was paralysed to act.

People had to prove their loyalty and for ethnic and religious minorities it sometimes resembled a protection racket where one had to engage in unhealthy and unprincipled compromises just to live and survive. Minorities and migrants have had hate directed against them and were scapegoated for any problem the country faced.

Strongmen populist culture of the last decade gave up the universals of the generations before for America first and in other countries, nation first, religion first, race first. The basis of its politics as President Trump clearly articulated recently was “dominance”. Equally was shunned and might became right. A rules-based order both nationally and internationally was given up for the handshake and the deal. Strongman governments were on a perpetual war footing both in words and action so that the population had no time to think, reflect and organise differently. They never left you alone, constantly mobilising against some enemy imagined or actual.

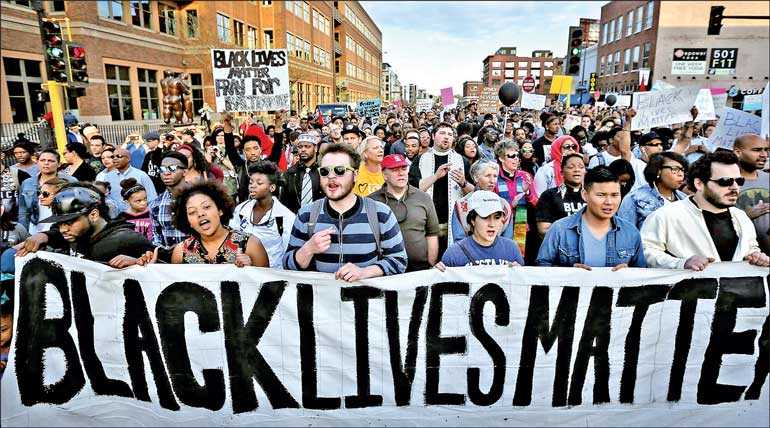

Just when the generations coming before began to reconcile to a different national and world order based on dominance devoid of humanism, young people began to mobilise in the most unique and unusual ways. First came the climate change movement, headed by Greta Thunberg, then the Me Too movement, the Hong Kong democracy movement, the movement in India against the Citizenship Act and now Black Lives Matter. All these movements, some accompanied by violence, still hint at a new tomorrow where universal values and the struggle for freedom, equality, dignity and respect will again be normative and acceptable.

The role of the military in society

The Black Lives Matter campaign triggered many thoughts about a whole host of issues. For me one of the main questions that came up during the drama unfolding in Washington was the role of the military in society. American generals, Mattis, Powell, Mullen and so many others came out openly and harshly against President Trump trying to use the military to deal with civilian problems.

At first glance their statements were deeply disturbing because they hinted that external use of American military might have another standard, that external enemies would be the “other” and that undefined force could be used against them. This played into the fears the world has of America’s ambitions and goals. However, their refusal to use military force against their own civilians and to buttress civilian life is a question that is relevant to all societies.

This response of the generals of refusing to usurp the civilian came at a time when our President, now unhampered by a Parliament, set up a Task Force consisting of military and police officials to deal with “virtue” and discipline in our societies. What does this really mean? The language is very unclear. It may be a limited operation to strengthen the criminal justice process especially in drug enforcement but it does sound more ominous. These words virtue and discipline are very troubling because they have not been defined anywhere. The idea for ministries and departments of virtue and vice actually originated in Iran and then were also adopted by Saudi Arabia and led to the creation of religious policing.

I went as Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women to Afghanistan when the Taliban were ruling. One of their most important ministries was the Ministry on Vice and Virtue. I witnessed as religious police, mostly dressed in black, went about in open police jeeps with something like cricket bats in their hands. If a women exposed her ankle, if she was unaccompanied by a male, if a man was sporting an uncut beard, if anyone had videos or cassettes, these religious police would leap out of the jeep and batter the individual.

I am not implying that we will become that extreme but the idea that military men will police our virtue and discipline is very worrisome. Quite honestly, I do not think my idea of what is virtue and discipline is the same as theirs. My virtue is between my God, the law and me. It is not for some Task Force to police unless I have broken the law and then the Constitution and statutes have spelt out the due process. These type of Orwellian initiatives are really unnecessary.

If Westpoint, Sandhurst and Indian trained Generals say no to politics and usurping civil life where does this strange manifestation come from? Among authoritarian governments, very few place the military in front. Even in China it is the Communist Party that comes first and sets policy based on its contacts with people in the community and the grassroots. Do we want to become like Pakistan, or Myanmar or former Indonesia?

Are these our models? Are they successes? Do we want our military growing rice and running hotels and having an independent economic base? Is there no military man present or past who will come forward and say “Enough: you have crossed a line”. We hope all our leaders will contemplate these questions and that after the general elections there will be consensus and we will have a vibrant parliamentary democracy in place with the President as part of the executive.

Dominance and a conversation about race, religion and ethnicity

The second thought that came to my mind as I watched events unfold around the world is that we in Sri Lanka need to have that conversation about race, religion and ethnic harmony. From 2009 -2015 and from November till now there has been a one-way conversation, again about as President Trump would say, dominance, the dominance of a Sinhala Buddhist ideology.

From 2015 to November last year the Yahapalanaya Government tried half-heartedly to have a conversation about pluralism. Their lack of political will made pluralism a policy without an owner. Not only did that conversation fail miserably it traumatised the clergy and many members of the public and led to a backlash that is still being played out. So today we have the theory of Sinhala Buddhist dominance returning. And yet, enforced dominance in any sphere may get us a few years but is really not sustainable. It will lead to constant tension and we will never be a happy, relaxed society admired by the rest of the world.

If we ever decide to have that conversation, there are of course the well-known questions. There are the issues of justice, which has now been caricatured as an attempt to get at war heroes, the problem of terrorism and extremism within communities and the need for equality before the law. Most people are too intimidated by the “dominance” model today to say anything about these issues but there will be no healing unless they are confronted some day in an honest way.

Black lives matter is primarily about institutional racism. At the moment there is little space for such a conversation here. After the Easter attacks the majority feel that they are the victims and no matter how much one speaks about a new Constitution, argues about the right to bury your dead, challenges police, prosecutors and a judiciary that are insensitive if not hostile, expose politicians and lawmakers keen to play toward the base instincts of the majority community you will get no traction. Perhaps there will come a day when these issues can be addressed meaningfully but today we can only try. A few people on social media have kept these questions alive, have expressed their views and are pushing for answers but none are forthcoming only froth and hate speech.

If we listen to some members of the younger generation even in Sri Lanka they have moved beyond discussing only institutional racism and are into far more sophisticated conversations that get to the heart of hatred and prejudice in our society. While generations before spoke of the institutions of public life this generation also places a great deal of attention on the issue of “bias” and “privilege”, the prejudices we carry within ourselves. Their call is not only to fight for racial equality in public spaces but to confront and be self-aware of the prejudices we carry within us. Introspection and seeing our own demons is therefore the first step in having an honest conversation. I recently did an exercise with a young researcher and was confronted with and surprised by my own prejudices, biases and stereotypes even within the overall framework of human rights and social justice.

Another concept often used by young people in these movements is the concept of “safety”. Older generations are used to vitriolic, harsh speech that in certain contexts may become hate speech. The age of the internet has also made everyone aware that we now have an arena that can basically destroy people over night. Research is making us more aware that in certain contexts, women, minorities, people of different classes, people with disabilities, people with different sexual orientation do not enjoy privilege and do not feel safe to speak or work freely. They rarely express their voice in Parliament or the boardroom.

To get the best out of this country it is everyone’s duty to make spaces safe for everyone. This should be true at the national and community level. Sri Lanka today may be high on security with our omnipresent armed forces but it is not a safe place to speak or work for many. There is a difference between security and safety.

Youth take the lead

With the coronavirus pandemic still being a major factor, the crowds that turned out to protest for Black Lives Matter were overwhelmingly young. Old people had to stay at home. The organisers too were very young. In 2013 three black women, Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors and Opal Tometi began the BlackLivesMatter hashtag and then the movement. The project is now a member led global network of over 40 chapters. Their activity is on the Internet and at the community level where they build local power to intervene if violence is inflicted on black people.

President Donald Trump and his altright counterparts in Europe have caused a backlash with the rise of militant, anti fascist hashtags and movements such as Antifa and Anonymous who have membership all over the world. These movements are determined to combat fascism and racism even with violence. Though small in number and potentially destructive they have helped transform the narrative of the mainstream to make antifascism a legitimate cause. Their fury against fascism and racism only matches their counterpart. Again these movements are overwhelmingly young.

This generation of young people in many parts of the world is then different to the generation that immediately predates it, the tech generation that led the international revolution on the Internet and technology but were often apolitical, This present generation is also technology oriented but direct their energy toward social causes and they are very proactive. Beginning with Greta Thunberg’s “How dare you?” speech they are not only into systemic reform but also personal transformation. Young people have basically led the mobilisation on Climate Change, Black Lives Matter, the Me Too Movement as well as democracy and equality movements in India and China.

The refreshing part of these movements is that they are global and universal in character. The ostrich with the head in the sand era of my nation first and only is slowly giving birth to international movements for protection of the environment, equality, democracy and anti-colonialism. It is important to note that Black Lives Matter has chapters in forty countries. These movements are also decentralised, member driven and not donor driven. The great gift of the internet is that it makes such movements possible.

And yet we must also recognise that these are only movements with no real desire of actually capturing state power as a movement. Like the Occupy movement in 2012 they are decentralised, purposefully lacking in hierarchy and organisation. They want to stimulate thought and get networks to respond. The politics must follow thereafter. Their preference is for community level activism by local people, relying on these local people to defend and protect their rights with the broad support of networks of like-minded people from around the world.

The pandemic and the strongman

While young people are rising up against authoritarianism, the pandemic also added to the chink in the armour of strongman culture. Strongmen in many countries handled the pandemic badly. The US, Russia, Brazil have a staggering number of cases.

Ironically it was women leaders of democracies and women health ministers who did exceedingly well. Jacinda Arden of New Zealand has received a great deal of publicity. Health Minister K.K. Shailaja of Kerala led an aggressive public health approach with a Rapid Response Team that was set up the moment the virus broke in China. Sri Lanka’s initial attempts were lauded by the world even though it did not follow a strictly public health model.

Whither idealism? Whither hope?

Today we are faced with youth propelled movements around the world that challenge many of the systems we take for granted. This is not to say that all young people are involved. Many still support strongmen systems and dominance models of ethnic relations. In Sri Lanka for example voting patterns in the last election seem to suggest that.

Still the question always remains, whither the idealism? Whither the hope? For those of us who came of age in the 1960s and 1970s and who were slowly coming to terms with a very different world with dreadful governments, it is good to see that the torch has not died but is actually being passed to another generation, our children and grandchildren, where the values of freedom, equality, dignity and respect have again begun to inform the political and social battles that are being waged the world over.