Sunday Apr 20, 2025

Sunday Apr 20, 2025

Monday, 7 December 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The Federal Aviation Authority (FAA), the agency that regulates the US aviation industry, finally re-certified the Boeing 737 MAX – deeming it safe to carry passengers – on 20 November, by issuing Airworthiness Directive US-2020-24-02. This follows a comprehensive review of the aircraft, its systems and pilot-training requirements, which took almost two years to complete. The type was grounded worldwide following a second fatal crashes accident in March 2019.

The Federal Aviation Authority (FAA), the agency that regulates the US aviation industry, finally re-certified the Boeing 737 MAX – deeming it safe to carry passengers – on 20 November, by issuing Airworthiness Directive US-2020-24-02. This follows a comprehensive review of the aircraft, its systems and pilot-training requirements, which took almost two years to complete. The type was grounded worldwide following a second fatal crashes accident in March 2019.

The story of the grounding and the reasoning behind it were covered at length in these pages last year. The FAA now states that it is satisfied the aircraft is safe to carry passengers after Boeing introduced several modifications to the software controlling the MAX’s flight controls. Increased training for MAX pilots is also required, something the manufacturer had initially resisted when the type was introduced.

Certifying new aircraft types

Aircraft are typically certified as ‘safe’ by the regulator of the country in which it was designed and manufactured. Certification of a new type is a demanding process that very few national aviation regulators have the capability to accomplish. Bilateral Airworthiness Agreements (BAA) exist between the major manufacturing countries. These agreements allow the certification granted (for example) by EASA for aircraft to be registered under US-FAA rules.

The many new aircraft that were developed in the 1950s (see my blog for more on these) led to regulators in Europe and North America accumulating great expertise in the process. Disasters involving such aircraft as the de Havilland Comet and Lockheed L.188 Electra further honed their skill set. Today, the knowledge primarily resides with the USA’s FAA, Europe’s EASA and Transport Canada.

A more recent entrant to this rather elite club is Brazil’s regulator, the Agência Nacional de Aviação Civil (ANAC). Brazil has fostered a vibrant and successful aviation manufacturing industry since the 1960s, and developed the required regulatory skills in parallel. Concurrent with the media frenzy surrounding the MAX grounding, Canadian and European regulators have been conducting their own independent reviews of the type. In a rare divergence from the FAA’s clearance of the aircraft, the European Air Safety Agency (EASA) has stated that it will require ‘additional improvements’ before the MAX is permitted to fly passengers in Europe. Final approval by EASA is anticipated early in 2021. Transport Canada and Brazil’s regulator (airlines in both countries have sizeable MAX fleets) have not indicated when approval will be granted.

East vs. West

The other great reservoir of knowledge in this sphere lies in the former Soviet Union, which has many aircraft manufacturers. China too has been building its capability in this regard.

Over the years, the four ‘Western’ regulators have come to accept the veracity of each other’s processes, and granted approval to a new aircraft once the manufacturing country’s procedures have been satisfied under BAA protocols. This means that, for example, when Transport Canada certifies a new type (such as the Bombardier C-series now known as the Airbus A220), granting it approval to fly in the USA, Europe and Brazil with minimum additional testing is possible under the BAA. Other countries who lack the capability tend to go along with these cross-certifications, as developing the knowledge and skills required to certify new types is a long and expensive process.

China’s Civil Aviation Administration (CAAC) has historically accepted both ‘western’ and Soviet approvals. Soviet aircraft formed the bulk of China’s civil aircraft inventory for many years, but many American and European types were also employed, including the British-built Hawker Siddeley Trident in the 1960s.

No ‘western’ certification

The Soviet Union scorned having to seek type approvals for its aircraft from ‘Western’ regulators, so practically the entire stable of very capable ex-Soviet designs is not certified outside the Russian sphere. The one exception was the Yakovlev Yak-40 regional jet, which was certified in Italy and West Germany in the 1980s. A more recent design the Tupolev Tu-204 had Rolls-Royce RB211-535 engines and was supposed to undergo certification by EASA, but this was never completed.

In the absence of BAA-type approval, any civil user of the aircraft must retain the Russian (or that of another former USSR nation, such as Ukraine) registration, precluding almost all passenger applications and preventing local pilots from flying them. This applies to many aircraft used in the South Asian region. Military operators are exempt from this requirement of course, as long as they do not carry civilian passengers on a commercial basis.

China enters the aerospace game

China has progressed from initially building Soviet aircraft under license to ‘reverse engineering’ these types and improving on them. The CAAC has been gaining expertise in certifying new types, with the Harbin Y-12F regional turboprop being recently certified by the FAA under the BAA type-certification program. Under an agreement with McDonnell Douglas, several MD-80 aircraft were to be assembled in China but only a handful were built when production ended in 2001.

Another Chinese built aircraft, the Xian MA60, a large regional turbo-prop, was granted CAAC type certification in June 2000. However, there has been no attempt to validate this by seeking a similar endorsement from the FAA or EASA to date. The MA60 has suffered a number of fatal accidents, a fact that has probably contributed to this status.

In the absence of approval from a regulator outside China, the MA60 and all other Chinese aircraft are restricted from commercial use to any great extent, mainly due to insurance concerns. A number of Chinese-built aircraft, including the Harbin Y-12 and the Xian MA60 twin-turboprop transport, are in use by the Sri Lanka Air Force (SLAF). Interestingly, the MA60s employed by the SLAF were granted civil registrations by the CAASL for a short while, but have since been taken off the Sri Lankan regulator’s list of civil aircraft. The SLAF Y-12 aircraft is an earlier variant that is not covered by the FAA’s approval of the Y-12F.

COMAC C919

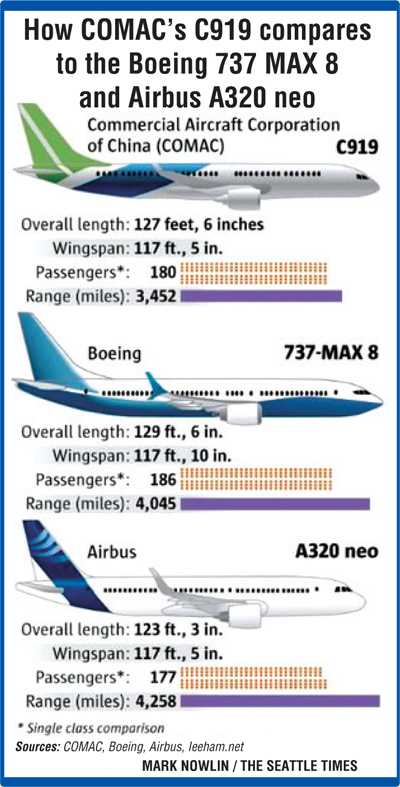

The Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China (COMAC) was set up by the Chinese government in 2008 in order to produce cutting-edge large commercial aircraft in the country. The company flew its flagship C919 at an airshow on 2 November; the first time the aircraft had been demonstrated publicly. Equipped with CFM LEAP-1C engines, the C919, in development since 2009, is a direct competitor to the Airbus A320 and Boeing 737 (see graphic above). To date, COMAC appears to have over 300 firm orders for the C919. Practically all these are from Chinese carriers excepting 20 from GECAS, a US-based aircraft leasing company. How many aircraft have actually been delivered and are in scheduled service with Chinese airlines, is hard to determine.

COMAC is currently seeking EASA certification for the C919 under the auspices of the Bilateral Airworthiness Agreement between China and the EU. The target date for completion is the last quarter of 2021. Success in accomplishing this will be a ‘coming of age’ moment for China’s industry. Such a development could well see COMAC becoming a significant player and breaking the Airbus-Boeing duopoly in the market.

Back to the MAX

The Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) was among the first to ground the MAX in March 2018, soon after the second accident occurred in Ethiopia. Subsequently, other regulators followed suit, with the FAA acting belatedly. As part of the re-certification process the FAA has mandated that pilots undergo training specific to the MAX, even if they currently fly other 737 variants. This is a crucial change as Boeing marketed the aircraft as being ‘no different’ to earlier models of the best-selling 737 that were first certified in the 1960s.

China was a large user of the MAX with almost 100 in service prior to the grounding, and many more on order. As readers of this column are aware, China’s domestic aviation sector is one of the few that have weathered the COVID-19 pandemic successfully. The latest data shows that domestic capacity in China exceeded 2019 levels by 10% in October and November of this year. This is in marked contrast to the rest of the world, where intra-European traffic has experienced a 70% reduction, and the domestic USA market contracted by around 40% in the same period compared to last year. (Data from Airbiz capacity review) Thanks to the effects of the pandemic, China’s domestic aviation sector has displaced the USA to be the world’s largest, a position it was not expected to reach for at least another decade.

When will the MAX start passenger flights again?

One US airline has stated that the MAX may be back in commercial service as early as December. The hundreds of airplanes that were placed in storage have to be modified (mainly a software upload) and prepared for service. This is a time-consuming procedure that could take a day or two for each aircraft. Crew training will also have to be completed and documentation submitted, thereby extending the duration of the process.

But with the USA struggling with a second wave of COVID, and authorities recommending that people do not travel even for the Thanksgiving holiday (the busiest travel weekend in the US), it is difficult to say whether this will happen, or whether there is even a need for it given such a low US domestic demand.

Overcoming passenger reluctance to fly on the MAX is another hurdle. However, social media is replete with vitriol relating to the pandemic and the recent US election. How much prominence the MAX will get is impossible to say.

Delivery issues and trade disputes

Over 300 MAX aircraft have already been delivered to airlines and another 400 or so are completed but not handed over. Some of these orders have since been cancelled, due to contractual clauses and the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. The recent trade dispute between the European Union and the US has meant that the World Trade Organization has approved tariffs of up to 15% on aircraft, which could add to Boeing’s woes.

Ironically, the only users that need the capacity immediately are Chinese domestic airlines. But given the current state of political tension between the USA and China, it is unlikely that the 737 MAX will be flying there anytime soon. Rather, China’s government will push for certification and manufacture of the C919 to reduce its reliance on foreign aircraft, thereby further distancing its economy from US influence and dependency.

Also worth noting is that the C919s CFM LEAP 1-C engines and many other components are manufactured in the USA. Worsening trade relations mean that COMAC could be placed under sanctions by the US Department of Commerce. This in turn could result in unfulfilled orders as China does not have the capability to build advanced aircraft engines, and is unlikely to be able to do so for many years.

Discover Kapruka, the leading online shopping platform in Sri Lanka, where you can conveniently send Gifts and Flowers to your loved ones for any event including Valentine ’s Day. Explore a wide range of popular Shopping Categories on Kapruka, including Toys, Groceries, Electronics, Birthday Cakes, Fruits, Chocolates, Flower Bouquets, Clothing, Watches, Lingerie, Gift Sets and Jewellery. Also if you’re interested in selling with Kapruka, Partner Central by Kapruka is the best solution to start with. Moreover, through Kapruka Global Shop, you can also enjoy the convenience of purchasing products from renowned platforms like Amazon and eBay and have them delivered to Sri Lanka.

Discover Kapruka, the leading online shopping platform in Sri Lanka, where you can conveniently send Gifts and Flowers to your loved ones for any event including Valentine ’s Day. Explore a wide range of popular Shopping Categories on Kapruka, including Toys, Groceries, Electronics, Birthday Cakes, Fruits, Chocolates, Flower Bouquets, Clothing, Watches, Lingerie, Gift Sets and Jewellery. Also if you’re interested in selling with Kapruka, Partner Central by Kapruka is the best solution to start with. Moreover, through Kapruka Global Shop, you can also enjoy the convenience of purchasing products from renowned platforms like Amazon and eBay and have them delivered to Sri Lanka.