Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Thursday, 7 September 2023 01:34 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Exploring Sri Lanka’s migratory trends

Context of the study

Context of the study

Key takeaways

Business as usual for migration

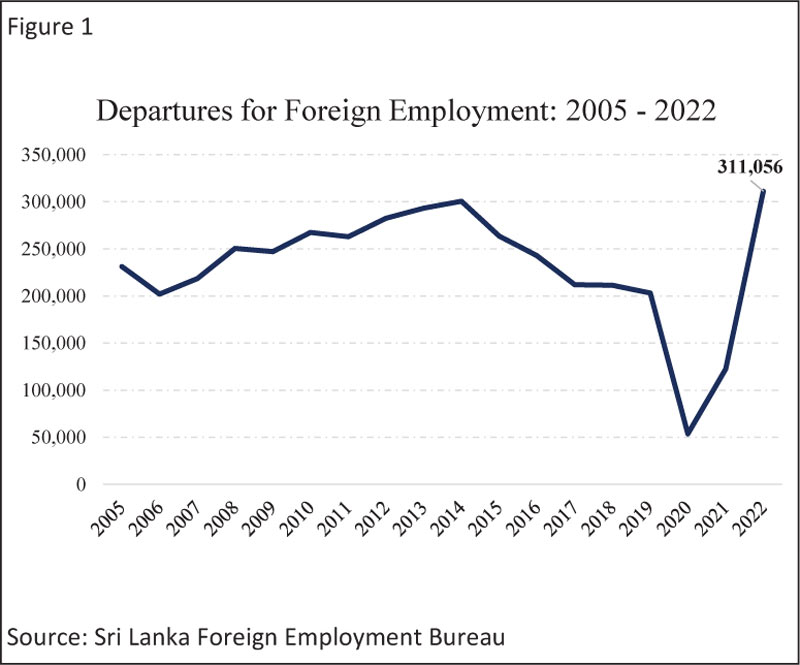

When the COVID-19 pandemic brought the entire globe to a standstill, Sri Lanka’s labour migration followed suit, hitting its all-time low since 1994 and standing at a mere 53,711 in 2020. In 2021, when both domestic and international mobility restrictions were alleviated, labour migration appeared to be returning to normalcy, inching closer to the pre-pandemic annual average of 245,000 (annual average calculated from 2005-2019).

In 2022, 311,056 citizens migrated for employment after a dramatic reduction for two years, reaching an all-time high going above the annual average indicated earlier. However, this recovery can be considered systematic post the pandemic given the processes which were on hold and those who could not make it out of the country during those trying years.

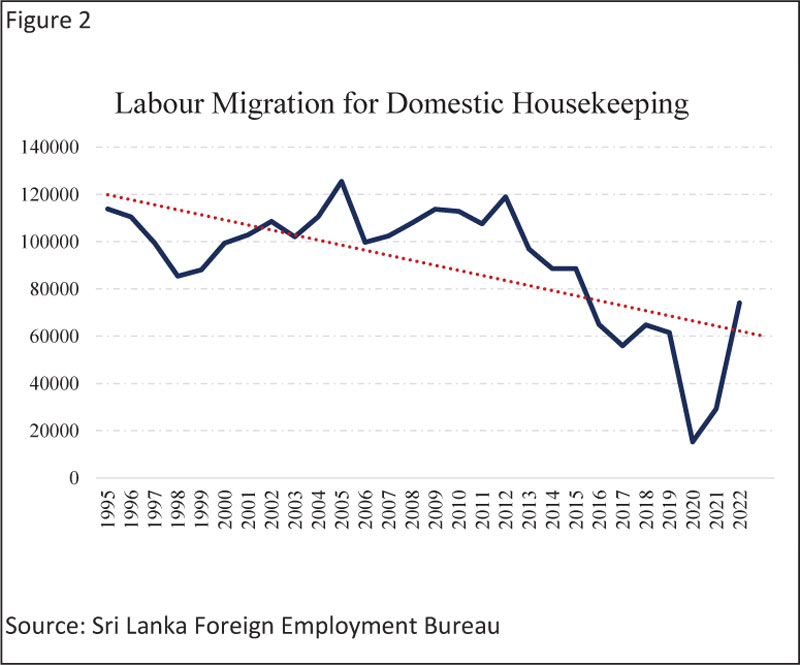

Domestic housekeeping no longer dominates labour migration in Sri Lanka

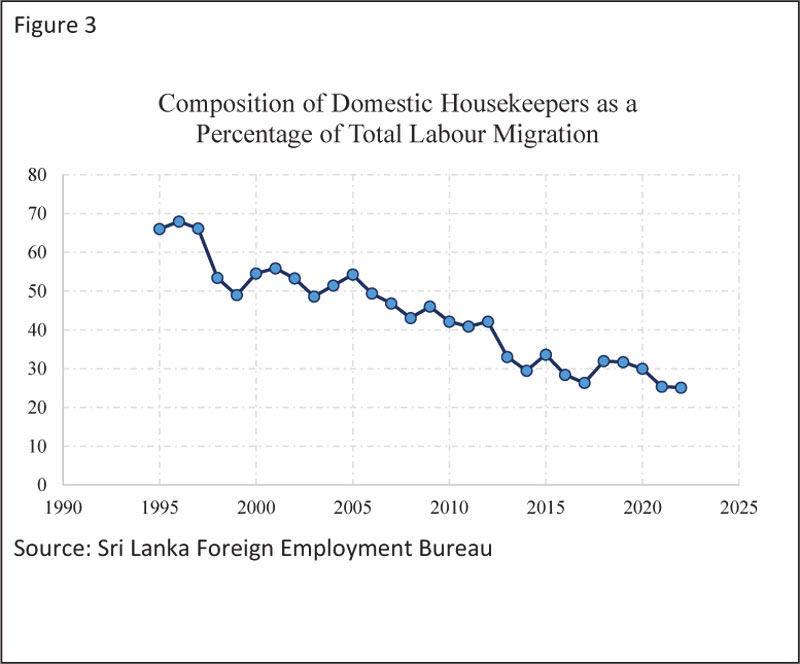

In the 1990s, domestic housekeepers made up nearly three fourths of total labour migrants. Latest data suggests that migration for domestic housekeeping has not seen a significant increase post pandemic and cannot be considered a significant contributor to the high levels of labour migration seen in 2022. In fact, the composition of those migrating to be employed as domestic housekeepers has systematically contracted over the years. At present, this figure has contracted to a mere one fourth (25% in 2022).

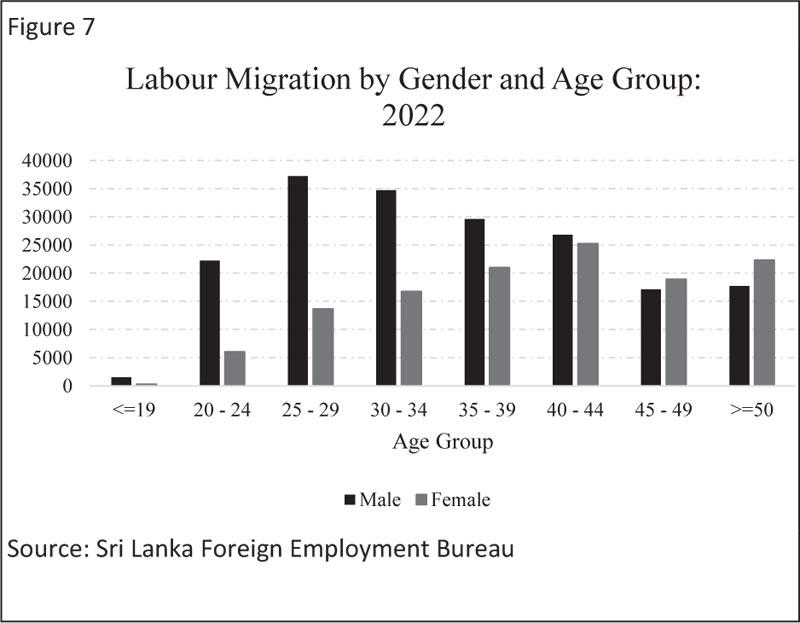

This trend also explains the shift in the gender composition of Sri Lanka’s migrant workers. In 1995, 66% of those that were migrating for employment were for domestic housekeeping positions. In the same year 73% of total labour migrants were females. The contraction in the domestic housekeeping component evident at present is reflected in the gender composition that appears to have balanced out over the years. In 2022, 60% of total labour migrants were males. While over 75% of females that migrate for employment are still engaged in the domestic housekeeping sector, this proportion also shows a decreasing trend.

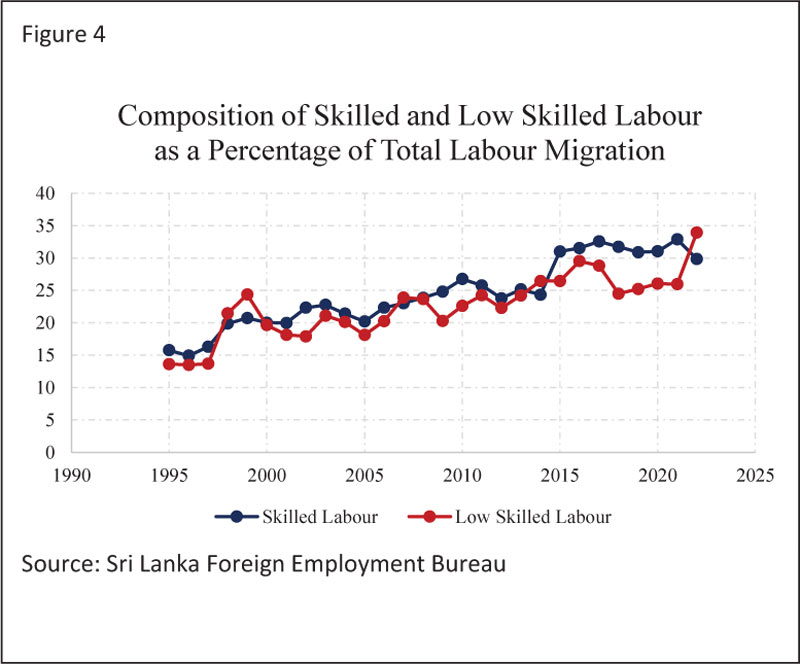

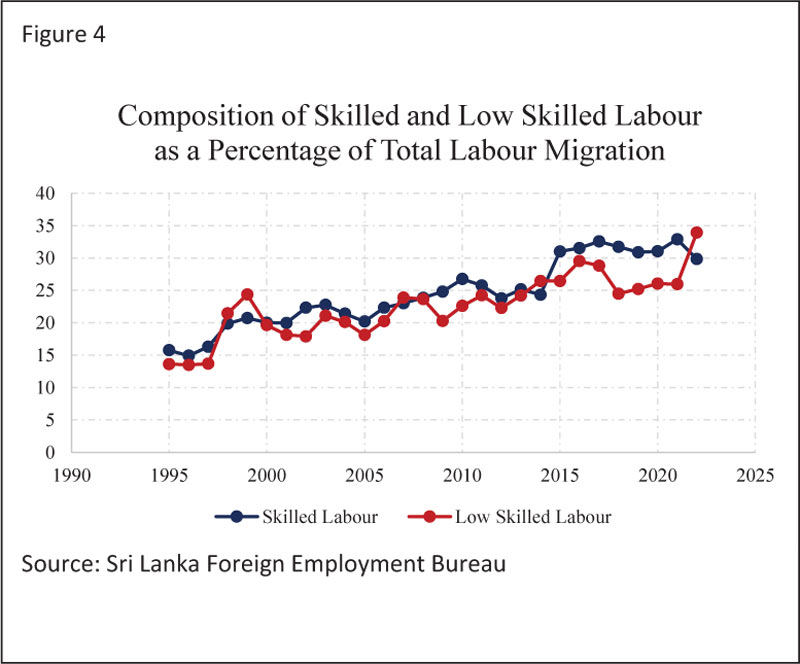

Migration of skilled and low-skilled labourers have risen systematically over the years

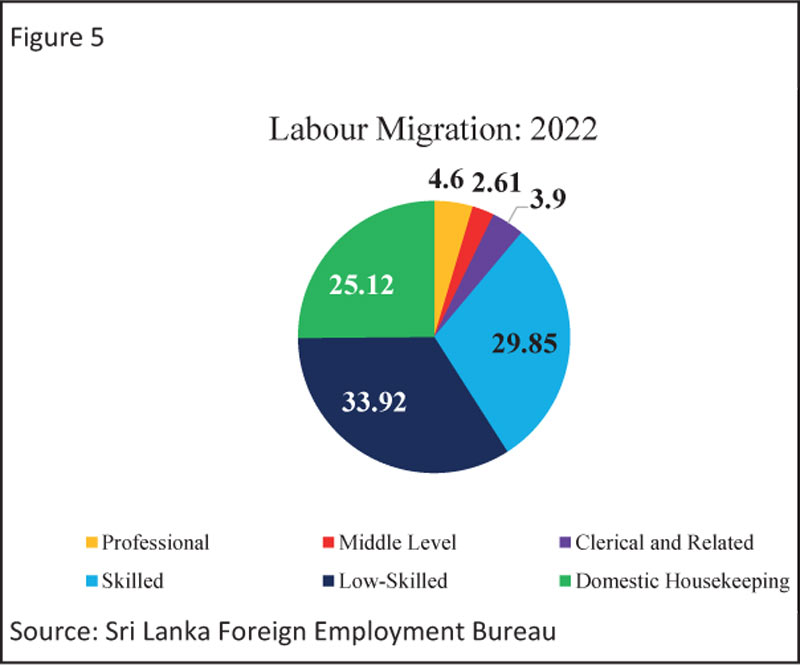

Trends seen in migration of skilled and low-skilled labourers suggest that each has grown approximately 4% to 5% respectively on an annual basis from 1995. While the numbers have been increasing over time in absolute terms, so has the percentage contribution from both segments in terms of total labour migration composition. Over time, low skilled labour migration has grown to the highest ever witnessed in 2022 at 33.9% while skilled labour stood at the second highest at 29.9%.

It must be noted that this growth in composition was gradual and systematic. In terms of skilled labour migration, between 1995 and 2002, its composition varied between 15-20%, gradually reaching 25% by 2010. This number then expanded to 30% in 2015 and ranged around 29-33% since.

Composition of low skilled migration followed a similar trend. It ranged between 13-20% in the decade from 1995 to 2005 and gradually rose to surpass the 25% threshold by 2015. Since then, it has largely varied between 25-29%, reaching over 30% in 2022.

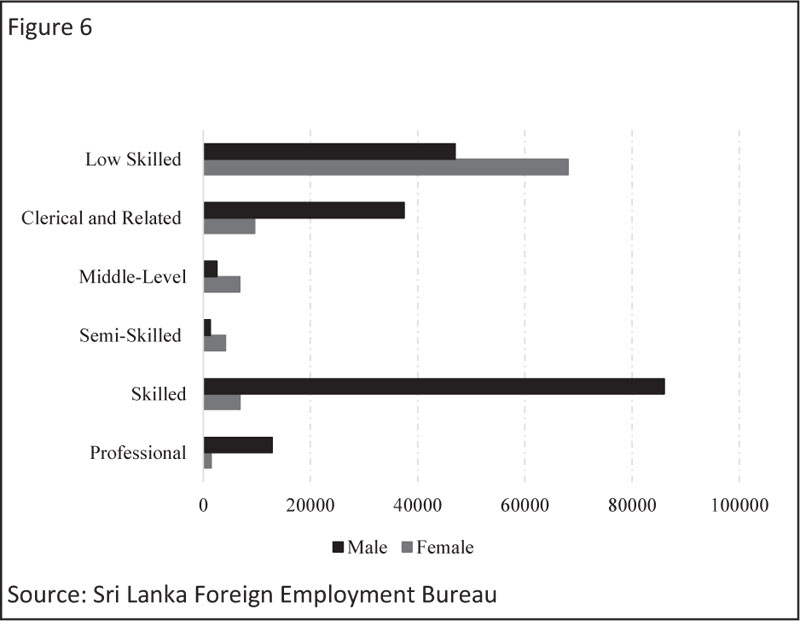

More women are taking up low-skilled jobs

From a gender perspective, a vast majority of labourers migrating for skilled labour are males. Since 1995 up to 2022, out of all male migrants more than 40% has left for skilled labour every single year. Conversely, out of female labour migrants, those employed for skilled labour has remained below 10% almost always during the same period. Nearly 70% of all female migrants have been leaving for domestic housekeeping jobs since 1995. 2022 was the only exception where this number dropped to around 60%. However, in the same year the composition of females leaving for low-skilled positions saw a noteworthy upsurge, rising to 30% whereas this figure has remained close to 15% historically.

A quick look at major Labour Migration Patterns of 2022

Low-skilled, skilled and domestic housekeeping take up bigger slices and gender disparity prevails albeit lesser

Geographically, migration isn’t limited to big city districts

Conclusion

The above data analysis shows that Sri Lanka has been showing increasing signs of brain drain over time, even though it’s felt more than ever at present.

The Sri Lanka Bureau of Foreign Employment Act No. 21 of 1985 states providing employment opportunities for Sri Lankans abroad as one of its objectives and it still advertises on its website related notices. While this might have been a requirement in the past, revisiting the role played by Government agencies, identifying necessary skills required to sustain the standard of living of the citizens, equipping individuals with the right skill set and creating conditions to retain such talent are a couple of policy decisions which need to be revisited in the light of brain drain gaining momentum in the public agenda.

(Niroshi Perera is the Head of Applied Research at Frontier Research, leading the inequality research arm, helping raise awareness on a variety of thematic issues. She was a Chevening Scholar and holds an MSc in Poverty, Inequality and Development from the University of Birmingham, UK. Her research interests are the care economy, and consumption and class inequality.)

(Akna Tennakoon is a research associate at Frontier Research, working predominantly on our sector and policy research reports. She is a graduate of the University of Colombo, and received the award for the Most Outstanding Research Paper under the theme “Role of Economic Policies during the Crisis” at the 18th South Asian Economics Students’ Meet (SAESM) for her thesis titled “Impact of Long-Term IMF Lending Facilities on Economic Growth of South Asian Countries”.)