Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Wednesday, 17 April 2024 03:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

What is required for medical education is a decentralised incentive-based solution that makes the best use of taxpayer funds

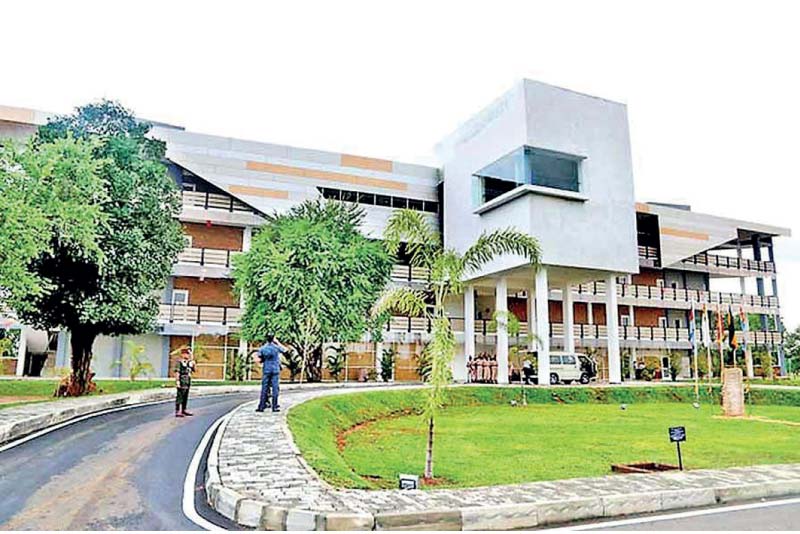

According to the University Grants Commission (UGC), the second most expensive undergraduate degree program offered by state universities is the MBBS (after dental). Battles over who gets to be a doctor under what terms have been ongoing since the 1980s with no clear resolution. Workaround measures implemented at various times are posing significant challenges, which are being met with further ad hoc remedies, the latest being the Cabinet decision to allow students satisfying UGC requirements to be admitted to the Kotelawala Defence University’s (KDU) medical faculty.

According to the University Grants Commission (UGC), the second most expensive undergraduate degree program offered by state universities is the MBBS (after dental). Battles over who gets to be a doctor under what terms have been ongoing since the 1980s with no clear resolution. Workaround measures implemented at various times are posing significant challenges, which are being met with further ad hoc remedies, the latest being the Cabinet decision to allow students satisfying UGC requirements to be admitted to the Kotelawala Defence University’s (KDU) medical faculty.

On the surface, this appears to be a liberalisation of access to medical education. But it is more than that. It is a desperate measure to shield the Treasury from having to bear the full cost of massive loan guarantees given to banks on behalf of the state-owned KDU which is unlikely to be able to repay the loans. The decision to prod the National School of Business Management (NSBM) into establishing another medical faculty may result in a similar problem in the next few years. Hopefully, understanding the KDU problem may avoid its repetition.

The immediate problem

The latest available annual report of the KDU lists two Treasury-guaranteed loans amounting to Rs. 35.5 billion from the state-owned National Savings Bank (NSB) obtained to build the teaching hospital. The capital repayment period is from September 2023 to September 2031 (96 months). KDU is yet to finish repaying two Treasury-guaranteed loans of Rs. 85 million and Rs. 750 million taken from the Bank of Ceylon several years ago. Assuming interest payments will continue to be paid by Treasury, KDU would have to pay Rs. 369.4 million a month as repayment of the hospital loan. It is unlikely that it can be done solely from the budgetary allocations of the Ministry of Defence, the fees of foreign students and from the hospital.

That means that Treasury will have to honour its guarantee, effective from July 2020 to September 2033, or the depositors of the NSB will have to take the hit, or both. The decision to permit the admission of fee-paying domestic students is an attempt to reduce the burden on Treasury and the risk to the NSB. These fees will not be adequate to meet KDU’s obligations fully. Negative impacts on Treasury (currently paying the interest on the loan) and the NSB (depositors) may be ameliorated, but not avoided.

What is done is done. What must be stopped is the issuance of Treasury guaranteed loans to educational institutions that have no realistic prospects of being able to repay them. That means no further Treasury-guaranteed loans to the NSBM (it is currently paying off the Rs. 6.7 billion balance on a Treasury-guaranteed loan from the Bank of Ceylon that has to be fully paid by end 2028) or any other educational institutions. Recall the much smaller Rs. 2.5 billion loan given for the Neville Fernando Teaching Hospital. The Bank of Ceylon is the unhappy owner of that hospital with no one to teach.

The short-term solution

The demand for affordable medical education (preferably fully paid by the State) is high from the influential middle class. The Sri Lanka Medical Council has accredited 12 medical/health science faculties, including the one at KDU, which until now was not open to domestic students not enlisted in the armed forces. It denied approval of the application by SAITM because it lacked a teaching hospital. Perhaps because of that, KDU appears to have built itself a gold-plated teaching hospital using a massive Rs. 35 billion loan in the belief that Treasury would repay it. The fiscal discipline required by the IMF program has put a crimp in that plan.

It is illogical to oppose the admission of fee-paying students from Sri Lanka or any country to KDU in the current circumstances. It is not possible to undo the wrong decisions of the past. All that can be done is to mitigate the harm. Taxpayers and the depositors of the NSB must be shielded from the losses caused by those decisions to the extent possible. It may be wise to put KDU into some form of receivership and entrust its management to professionals mandated to increase revenues and cut costs so that it can meet its obligations, reducing the burden on taxpayers.

The creation of new medical faculties using public funds should be stopped until a comprehensive solution to the problem of sustainably training doctors for the rapidly aging Sri Lankan population is implemented. This would not preclude any initiative, including by a foreign entity that does not draw on public funds.

The sustainable solution

In 2023, 53% of all capital expenditures in education went to the State universities. This is without counting the Treasury-guaranteed bank loans used for the building of a brand-new campus for the Institute of Technology at the University of Moratuwa and for construction of the NSBM facilities and KDU. Spending all this money for university buildings is sucking resources away from school education and everything else. Tertiary education opportunities must be expanded, but not at this cost.

There are no alternatives to tighter articulation of state investments in tertiary education and the desired social outcomes. No longer can mobilisation of non-state resources in the form of public-private partnerships and parental contributions be avoided. The fiscal discipline essential to getting the country out of crisis requires this.

What is required for medical education is a decentralised incentive-based solution that makes the best use of taxpayer funds a robust and fair credentialling system independent of the providers of educational services.

In most countries doctors are credentialled by a body independent of the providers of medical education. In Sri Lanka, this function is performed by the Accreditation Unit of the Sri Lanka Medical Council (AU-SLMC) which regulates two pathways leading to authorisation to work as a doctor in Sri Lanka.

The first path is to obtain an MBBS degree from a medical school accredited by the AU-SLMC. This includes the KDU, which is not part of the centralised z-score based admission system. There is not barrier to freeing all the medical faculties to manage their own admissions as is the case in most countries. Students graduating from the approved faculties may obtain a provisional registration and commence a year’s internship. The second path is for a graduate of the foreign university to take the ERPM examination conducted by AU-SLMC. Upon passing that examination, the student will be given a provisional registration and placed in an internship. Obviously, the first path is more attractive.

What matters to the AU-SLMC is whether the training is provided by qualified professors and the quality of the teaching hospital. Fulfilling these requirements is costly, as shown by the massive loans obtained by KDU and SAITM and by the fact that medical degrees are the second most expensive to provide within the state system. The range of diseases among patients at fee-levying hospitals being limited, access must also be obtained to non-fee-levying state hospitals, as is the case now for KDU students.

The first and most important action is to strengthen and make realistic the AU-SLMC mechanism. Without its reform, efforts to deploy non-state resources to widen medical education opportunities will fail, as was demonstrated by the SAITM saga.

Whether it is through a State university or through entities such as KDU or NSBM, it is extraordinarily costly to provide medical education. It is so costly that it does not make sense to spend money raised from taxes either directly or in the form of interest payments or honouring guarantees without an assurance that the recipients of medical education pay it back by serving within the state healthcare system.

The solution is to have higher education accounts for all who enrol in State-funded medical faculties, including KDU (and NSBM too if any state funds are used even as Treasury guarantees). Some would get scholarships that will create obligations that can be worked off by serving in the state healthcare system. The more remote it is, the faster would be the pay back. If at any stage the trained physician wishes to leave the State service or the country, the remainder in the account would have to be repaid. The same would apply if they wish to move to locations with greater channelling opportunities. Those who are not given scholarships or decline them will have obligations proportionate to the public funds used by them.

Without higher education accounts and obligations tied to scholarships, broadening medical education amounts to spending taxpayer money to train doctors for foreign countries. Whether it is direct funding from the consolidated fund or through Treasury guarantees, what must be kept in mind is what will not be funded if all this money is poured into medical education. If Treasury honours the guarantee it gave for the KDU loan, that will Rs. 35 billion that will have to be cut from the budget allocation for maintenance of non-fee-levying hospitals or from road maintenance. What does the country gain from such profligacy?