Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Tuesday, 28 November 2023 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The push for privatisation of SOEs, public goods and services, the liberalisation of markets, and the increased indirect taxes on working people are reflective of an anti-working people commercial budget

By Madhulika Gunawardena and Sinthuja Sritharan

Sri Lanka’s Budget 2024 follows the IMF package signed in March 2023. While President Ranil Wickremesinghe calls it a “welfare” budget, it is in fact proposing severe austerity measures. This Budget is quintessentially a commercial budget serving multi-national businesses and local elite interests. It sets a neoliberal trajectory in line with international financial institutions, particularly the IMF and World Bank. It also reinforces the local guardians of “free” markets and frames it as the only way forward to address corruption.

The Budget seeks to defund the public sector and sets up the conditions for privatising public goods and services. It further prioritises agriculture modernisation over food security, allocates bare minimum social welfare transfers that adhere to IMF austerity conditions, and shifts the burden of revenue generation to working people through indirect taxation. The real impact of the Budget will be to systematically undermine peoples’ well-being and marginalise women, elders, children and persons with disabilities.

Public debt and investment

A primary IMF condition is that Sri Lanka should maintain a gross financing need of 4.5% in servicing its external debt starting from 2027. Sri Lanka’s 2024 Budget adheres to this condition by allocating a whopping 38% of total expenditure for debt repayment. Additionally, the debt ceiling has increased from Rs. 3,900 billion to Rs. 7,350 billion with the intention of repaying and rolling over debt.

Sri Lanka’s GDP contracted by 7.8% in 2022. And even as private sector investment continues to deteriorate with the contracting economy, the Government should take counter-cyclical measures of investment in the economy and people’s well-being. However, according to the 2024 Budget Estimates, public investment will drop to 3.8% of GDP next year compared to 4.2% of GDP in 2022. The Government’s Budget proposals (refer to Annex 3 of the Budget speech) of Rs. 224.5 billion, which amounts to 0.7% of the estimated GDP for 2024 (author calculations based on 2024 Budget Estimates). In this context, the Budget proposals and the allocated capital expenditure are likely to be cut by the Government if revenues do not rise, and the mandated 0.8% primary budget surplus (calculated as revenue minus expenditure without considering debt servicing) for next year cannot be met.

Revenues and taxes

Despite the unmet ambitiously high revenue targets for 2023, the Government sets another target of increasing tax revenue by 47% in 2024. Accompanying this is a 107% increase in VAT revenues as opposed to a 25% increase in direct taxes. These regressive tax reforms include increasing VAT rates to 18%, and removing exemptions on VAT and SVAT. For example, poultry feed is not exempted from VAT which will contribute to the increase in cost of production, thereby reducing the affordability of eggs.

SOE reforms, privatisation, exports, and trade

As bluntly put by the IMF, to ensure that SOEs run on a “commercial basis,” the Government will continue “cost recovery” pricing mechanisms for the essential public utilities; electricity, fuel, and LP gas. Since 2022, electricity costs have increased by 400% which would not only instil producer-led inflation but also wage repression. The result is that 500,000 households have been disconnected from the electricity grid this year. Furthermore, the price hikes have also intensified the stress on care work. As Colombo Urban Lab iterates, these cost-recovery pricing mechanisms have pushed women to take labour and time-intensive means for cooking, cleaning, etc. to reduce electricity consumption. Where are the women in this Budget?

SOEs will no longer be capitalised or supported by Government funding, leading to either severe price hikes for services or privatisation of these public services themselves. While the budget proposes to recapitalise the Bank of Ceylon and People’s Bank to bring about financial stability, this bail-out is conditional on the divestment of 20% of their shares. In other words, this initiates the privatisation of the state banking sector.

With greater emphasis on trade liberalisation and investor-friendly reforms, this Budget proposes 60 new laws and amendments including land reforms in urban, rural, and estate sectors. This fast-tracked IMF budget is a prelude to the mass dispossession of the working people whether it is through their loss of land due to debt distress or the loss of welfare entitlements critical for their well-being.

Social welfare and dispossession

The Rs. 10,000 monthly cost of living wage hike for public sector workers is at the heart of this Budget proposal’s welfarism. Three concerns illustrate the limited character of this relief. First, as per the August 2023 poverty line, the minimum expenditure for a family of four to meet basic needs is Rs. 64,000. And this relief is only for State sector workers. Second, the real value of wages when compared to 2021 price levels (NCPI, September 2023) reduces by 51%. Thus the real value of the public sector wage hike is on the order of Rs. 4,900. This proposal to alleviate the cost of living is further undermined by the VAT increase and the 2 additional electricity tariff hikes expected in 2024.

On the contrary, the Government claims to increase spending on social safety cash transfers for Aswesuma, disabled persons, elders, and chronic kidney disease patients. The real value of these cash assistances again diminishes due to the above three effects. Moreover, total expenditure on these expanded social safety nets as a percentage of estimated GDP for 2024 remains at 0.65%. This IMF-mandated social protection floor does not vary much from the historically observed expenditure in Sri Lanka.

The proposal of Rs. 250 million to enhance food security, ensure the supply of essential food items to consumers, and support small and medium-scale food producers, only amounts to 0.001% of the GDP. Moreover, the budgetary allocation for food programs, including Thriposha, school meals, etc. only amounts to 0.13% of GDP. These allocations are supposedly meant to respond to the 62% of households, who according to UNICEF (2023), purchase food on credit. With increased food and energy prices, this budget provides little relief to women who are struggling with household provisioning.

In terms of the food system, proposals for agriculture emphasise commercial agriculture projects and the cultivation of export-oriented cash crops, with a focus on agro-modernisation. Divestiture of state lands under State Plantation Corporation, Mahaweli Zones, etc. are to be allocated for large-scale agricultural activities infringing the production sovereignty of small-scale farmers. This commercialisation repeats in the fisheries sector where Public Private Partnerships on fishing ports are to be introduced to “minimise wastage and enhance overall productivity.”

Spending on education and health

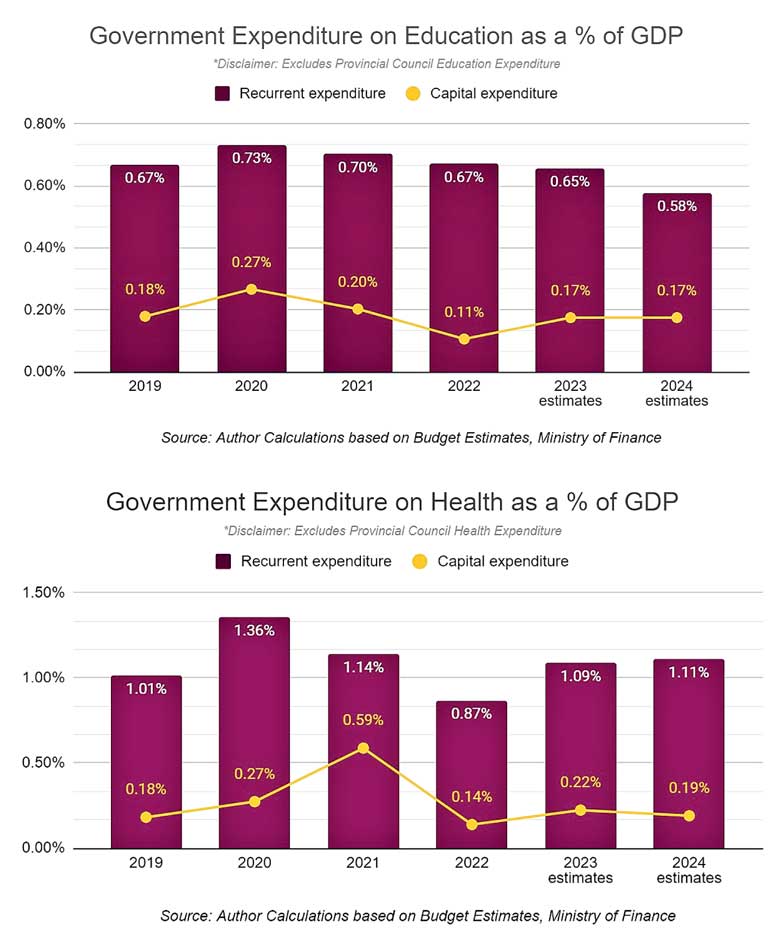

Allocations for the Ministries of Education and Health have been diminishing over the last five years, as illustrated below. As capital expenditure experiences a decline, it is noteworthy that the overall GDP is also in a state of contraction. In light of this situation, a heightened level of investment becomes imperative to alleviate the social suffering intensifying with the economic crisis. While the data we have does not include allocations for provincial education and health services, the declining trend of Central Government spending reflects the abandonment of free education and healthcare systems, which have been the two strongest pillars of human development in Sri Lanka.

With the value of cash assistance being abysmally low and targeting excluding many needy households, expanding social security to tangible protections such as meal programs, subsidies on electricity and essential goods and services, and comprehensive access to healthcare and education, are critical when reimagining and implementing social security during this crisis. In this context, the focus on cash relief allocation as social welfare is a fig leaf compared to the scale of the crisis. The push for privatisation of SOEs, public goods and services, the liberalisation of markets, and the increased indirect taxes on working people are reflective of an anti-working people commercial budget.

This research is supported by the Law and Society Trust for a project on Debt Restructuring led by Dr. Ahilan Kadirgamar.

References:

Colombo Urban Lab, 2023. Breaking Point: Impact of Sri Lanka’s Economic Crisis on Colombo’s Working Class Poor. Policy Brief. April 2023.

Ministry of Finance, 2022. Annual Report 2022.

UNICEF, 2023. UNICEF Sri Lanka Humanitarian Situation Report No. 1 (Economic Crisis): January-June 2023