Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Wednesday, 24 February 2021 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Rumours about ‘sterilisation candies’

By Dishani Senaratne

Why does social media burst out with hateful and divisive expressions against minority ethnic and religious groups? What lies behind the often seemingly coordinated hate speech and dis-information campaigns that in turn spark a further flood of ‘echoing’ spontaneous online outbursts by people?

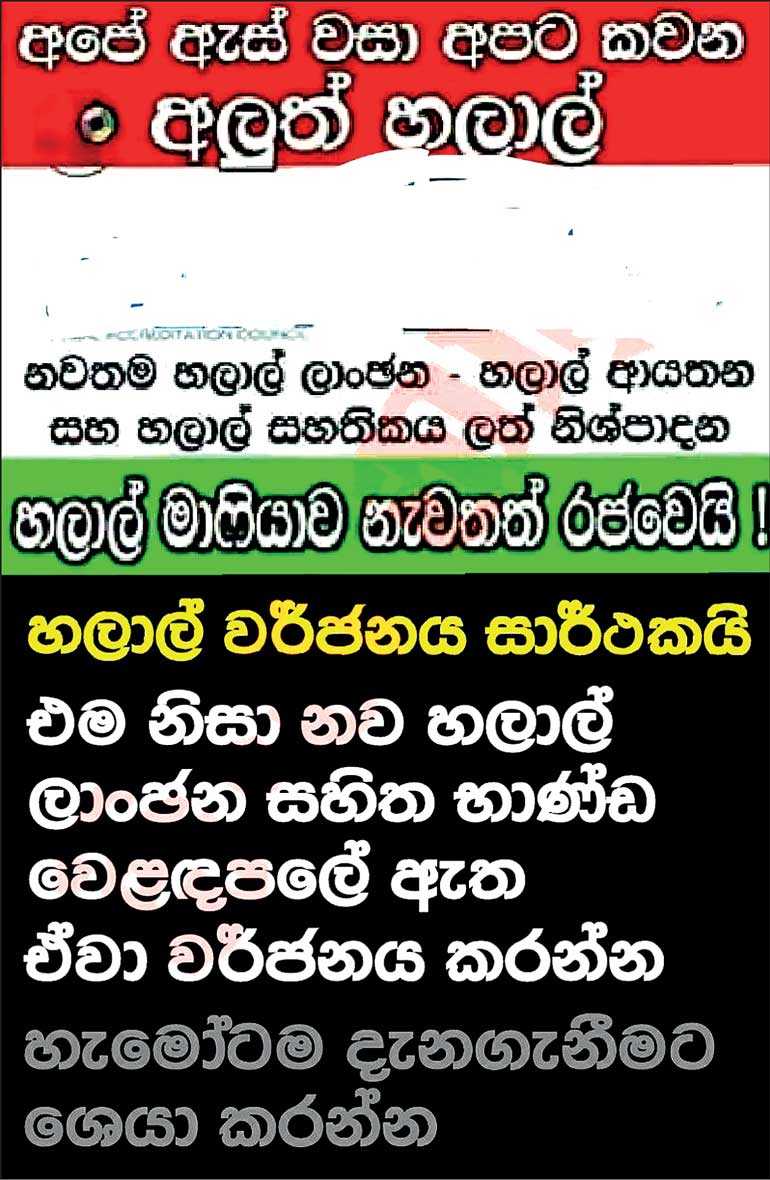

In the post-2009 era, the ever-increasing cyber rhetoric against the Muslims, according to some analysts, is a reflection of long-standing perceived economic rivalries between the Sinhalese and the Muslims. Notably the first anti-Muslim outburst was an ‘anti-Halal’ campaign that directly affected the country’s flourishing food industry and retail businesses. Later came the openly violent riots in Aluthgama and then in Digana, in which the principal targets were Muslim-owned businesses. The online furore, entirely false, over infertility-causing tablets (‘vanda pethi’) as well as other disease-spreading actions also explicitly targeted Muslim-owned businesses.

With the 2019 Easter bombings, Sri Lanka experienced Muslim-on-Christian violence for the first time in its history. While the then administration continued to make confusing and contradictory statements about the terror attacks, the already existing anti-Muslim sentiments hit new heights in cyberspace, notwithstanding the social media blackout that was immediately imposed to rein in mis-information.

One such video that went viral on the internet depicted the police arresting a man dressed in a burqa, who the posts claim is one of the perpetrators of the Easter bombings. However, this video had actually been circulated since 2018 showing that the man had disguised himself with a burqa to conceal his identity to attack someone over a financial dispute, an AFP Fact Check article published four days after the Easter bombings pointed out.

Against the backdrop of the ban on face coverings in public as a security measure, a bout of apparent reprisal anti-Muslim attacks erupted in Chilaw later spreading to Kuliyapitiya and Minuwangoda, nearly a month after the bombings. Fawz Hotel, on the Minuwangoda-Airport Road, dating back to the 1970s, was one of many Muslim-owned businesses that was vandalised by unruly mobs, a Daily Mirror article by Piyumi Fonseka reported. Diamond Pasta Ltd. in Minuwangoda, Sri Lanka’s largest pasta manufacturing plant, was destroyed during the violence on 13 May 2019, Darshana Abayasingha reported in a Daily FT article. Apart from these physical attacks, coordinated racist propaganda against ‘Muslim-owned businesses’ re-surfaced on social media, urging the Sinhalese community to boycott such products and services. With such social media allegations mounting following incidents of mob violence, Pickme Chairman Ajit Gunewardene, a distinguished corporate personality, in a news media statement pointed out that the widely shared images pertaining to his company had clearly been digitally edited.

Claiming that students who use the long popular ‘Atlas’ products had been ridiculed in certain schools, Atlas Axilia’s management, in a media briefing called for countering hate speech campaigns. Such incidents show how certain extremist individuals and organisations leverage conditions of political and social unrest to further their commercial interests.

Adding fuel to the fire, a Sinhala daily carried a controversial article in May 2019 claiming that a Muslim doctor in Kurunegala had ‘forcibly sterilised’ many Sinhalese women. This phenomenon of perceived ‘enforced sterilisation of Sinhalese women’ can be traced back to 1960s, according to Darshi Thoradeniya’s 2014 scholarly text ‘Women’s Health as State Strategy: Sri Lanka’s Twentieth Century’. Prominent medical specialist Dr. Siva Chinnatamby, who spearheaded scientific trials for oral contraceptive pills in Sri Lanka, was accused of ‘attempting to disturb the ethnic balance of the country’ by using vanda ‘beheth/pethi’ (sterilisation drugs/pills), Thoradeniya further noted.

Malevolent refrain

In the post-2009 era, vanda pethi became a malevolent refrain during many incidents of targeted violence against the Muslim community, despite medical experts disproving their existence. In 2018, several Muslim shops and a mosque in Ampara were reportedly attacked by Sinhalese mobs over the supposed mixing of vanda pethi in hotel food that was depicted in a video that soon went viral on the internet. In consequence, anti-Muslim violence broke out in Udispattuwa later spreading to Digana and other areas, following the death of a Sinhalese driver in a clash between several Muslim youths over an incident of road rage.

Back in 2014, in the run-up to the Aluthgama and Beruwela communal riots, the buzzword of vanda pethi alongside an anti-Halal campaign were propagated by various groups led by some Buddhist monks, including the Bodu Bala Sena (BBS). Nearly a month after these gory riots, the Nolimit Panadura store was destroyed by fire, shaking the business community anew. In the previous year, some Buddhist monks were seen leading an attack on another ‘Muslim-owned’ clothing warehouse in Pepiliyana, Nugegoda. During that time, rumours had rapidly spread on social media that ‘Muslim-owned’ clothing stores were selling products ranging from ‘candies mixed with contraceptive pills’ to ‘contraceptive jells embedded on women’s lingerie,’ aimed at ‘suppressing the population growth of the Sinhalese.’

Regrettably, successive governments’ complacency over combatting such false and misleading discourses affected not only the wider Muslim populace but also their businesses, as evidenced by the subsequent spate of anti-Muslim assaults.

In contrast, the Tamil business community was spared from cyber antagonism during the decades-long civil war partly due to non-existence of social media at the time. Despite the lack of the Internet, however, the pogrom of July 1983 is a shocking manifestation of how Sinhalese mobs attacked, burned, looted and killed Tamil targets, including their businesses. Adding insult to injury, the then President J.R. Jayewardene dwelt on Sinhalese grievances sans offering any apology to the Tamils in his belated address to the nation in the aftermath of the violence.

With the escalation of the Eelamist insurgency in the late 1980s, the predominantly state-owned news media continued to downplay the loss of human lives and destruction of properties in Tamil-majority areas in order to galvanise Sinhalese support for the war against the insurgency. With the sudden death in 2003 of Ven. Gangodawila Soma Thero, attacks against the Christian community and churches took place on an unprecedented scale but the practice of singling out businesses as ‘Christian-owned’ was almost non-existent.

In Rwanda, the radio station RTLM gained notoriety for employing hate-mongering rhetoric, inciting the majority Hutus against the ethnic Tutsis which spilled over into the infamous 1994 genocide. Rwanda exemplified how partisan media was instrumental in stoking ethnic bias and stereotypes in the pre-internet era.

More recently, during the 2014 communal riots in Aluthgama and Beruwela, the role of social media compensated for the notably subdued mainstream news media reportage of that violence against the Muslim community. In a shameful re-enactment of the role played by state-owned media in constructing narratives in previous times of turbulence, the Muslim community was held culpable of the mayhem that had occurred in Aluthgama and Beruwela.

Social hostility towards the Muslims who have been historically engaged in trade and commerce dates back to the British colonial period. Widespread rumours about Muslims provided the initial spark that ignited the 1915 riots, the earliest recorded violence targeting Muslim people and bazaars across the country. The rumour about a conflict over a religious procession held in Kandy is commonly identified as the immediate reason for the unrest.

At a glance, the ethnic minorities feature prominently in the entrepreneurial landscape in the commercial capital of Colombo. The quintessential commercial hub of Pettah where there is an overwhelming concentration of Tamil and Muslim traders, is an example of the prominence.

Decades after the 1915 Sinhalese-Muslim riots, the Muslim businesses have again begun to be viewed with scepticism with the emergence of anti-Muslim propaganda in our post-war life. There is a commonly held belief that transnational Muslim networks, particularly the affluent petroleum tycoons based in West Asia, render financial assistance to their Sri Lankan counterparts with blessings of religious leaders, placing the latter far ahead of their local economic competitors.

Moreover, the rivalries between Muslim and non-Muslim entrepreneurs are further compounded by the perception that the Islamic finance system practiced primarily by Muslims serves as a key driving factor of rapid business growth. As a reactive phenomenon, informal boycott of certain ‘Sinhalese-owned businesses’ have come to the fore in the offline world, but their intensity and frequency are significantly minimal.

Another deeply troubling point is the communal tensions between the Tamils and the Muslims that have spread to the economic sector. Unlike the Muslims in the south who have divergent interests based on trade and commerce, the vast majority of Muslims who live in the north and east share many common aspects with the Tamils including the Tamil language, a 2011 research paper has noted. This paper, titled Some Critical Notes on the Non-Tamil Identity of the Muslims of Sri Lanka, and on Tamil-Muslim Relations, is jointly authored by A.R.M. Imtiyaz and S. Ratnajeevan H. Hoole.

Under a predominantly southern leadership, the Muslims who speak the Tamil language, sought a social formation based on religion to win a distinct ethnic recognition from the Tamils, thereby rupturing the relationship between the two communities, Imtiyaz and Hoole further point out.

Moreover, the bloody Kattankudy mosque massacre committed by the LTTE in 1990, followed by the expulsion of the Muslim community from the Northern Province, further polarised the Tamils and Muslims during the war. Such divisions, however, have only minimally fed into the present-day social media furore.

In light of these factors, episodic anti-Muslim violence clearly goes beyond mere acts of ‘retaliation.’ As long as people are divided along ethnic and religious lines, individuals and groups with vested interests will continue to exploit social media as a tool to augment hateful and divisive discourses which in turn imperils Sri Lanka’s fragile economy.

Anti-Halal propaganda