Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Monday, 10 December 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The most frequently cited example of the bystander effect is the brutal murder of a young woman named Catherine “Kitty” Genovese. On 13 March 1964, Genovese was returning home from work; as she approached her apartment entrance, she was attacked and stabbed by a man later identified as Winston Moseley. Despite Genovese’s repeated calls for help, none of the dozen or so people in the nearby apartment building who heard her cries called police to report the incident.

It was indeed shocking to hear the inactivity of the observers in preventing a murder committed by a group of school students in Matara recently. It was equally shocking to see a video circulated in social media, showing how a person strangled his fiancée to death while his friends were video-recording it. At a time when many are focusing on mega political issues, I thought of reflecting on a relatively neglected area of public consciousness.

Overview

There is a Sinhala proverb which goes as “Thaman hisata thama athamaya sevanala” (It is only one’s hand is the shelter / shadow for one’s head). In the spate of a wide range of human fatalities reported by local media, Genovese Effect offer rich insights of human behaviour, particularly that of bystanders of an event. It essentially refers to the phenomenon in which the greater the number of people present, the less likely people are to help a person in distress. When an emergency situation occurs, observers are more likely to take action if there are few or no other witnesses.

The bystander effect essentially refers to the phenomenon in which the greater the number of people present, the less likely people are to help a person in distress. When an emergency situation occurs, observers are more likely to take action if there are few or no other witnesses.

In a series of classic studies, researchers Bibb Latane and John Darley found that the amount of time it takes the participant to take action and seek help varies depending on how many other observers are in the room. In one experiment, subjects were placed in one of three treatment conditions: alone in a room, with two other participants or with two confederates who pretended to be normal participants.

As the participants sat filling out questionnaires, smoke began to fill the room. When participants were alone, 75% reported the smoke to the experimenters. In contrast, just 38% of participants in a room with two other people reported the smoke. In the final group, the two confederates in the experiment noted the smoke and then ignored it, which resulted in only 10% of the participants reporting the smoke.

Mind of a bystander

According to Psychology Today, “the social paralysis described by the bystander effect has implications for how we behave not only on city streets filled with strangers, but any place where we work or socialise.” When individuals relinquish responsibility for addressing a problem, the potential negative outcomes are wide-ranging—from minor household issues that housemates collectively avoid dealing with to violence and abuse that go unchecked. Some efforts have been made, including on college campuses, to encourage people to be “active bystanders” and fight the urge to step aside when someone is in trouble.

According to Kendra Cherry, there are two major factors that contribute to the bystander effect. First, the presence of other people creates a diffusion of responsibility. The second reason is the need to behave in correct and socially acceptable ways.

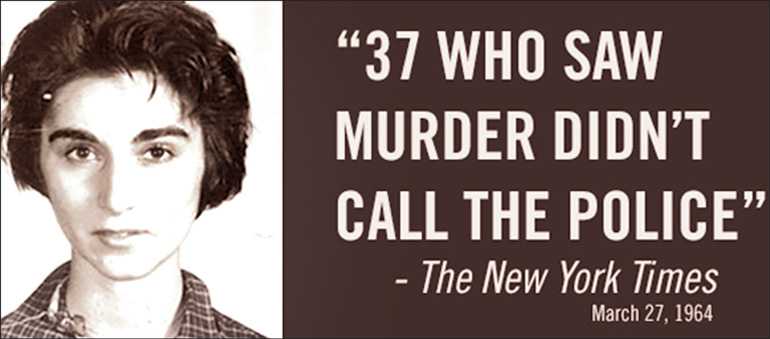

Catherine Genovese

The most frequently cited example of the bystander effect in introductory psychology textbooks is the brutal murder of a young woman named Catherine “Kitty” Genovese. On Friday, March 13, 1964, 28-year-old Genovese was returning home from work. As she approached her apartment entrance, she was attacked and stabbed by a man later identified as Winston Moseley.

Despite Genovese’s repeated calls for help, none of the dozen or so people in the nearby apartment building who heard her cries called police to report the incident. The attack first began at 3:20 am, but it was not until 3:50 am that someone first contacted police.

Initially reported in a 1964 New York Times article, the story sensationalised the case and reported a number of factual inaccuracies. While frequently cited in psychology textbooks, an article in the September 2007 issue of American Psychologist concluded that the story is largely misrepresented mostly due to the inaccuracies repeatedly published in newspaper articles and psychology textbooks.

“Bus 44” and bystander effect

“Bus 44” is an award-winning short film written and directed by Chinese-American filmmaker Dayyan Eng in 2001, prominently highlighting the bystander effect. Based on a true story, “Bus 44” takes place on the outskirts of a small town and tells the story of a bus driver (Gong) and her passengers’ encounter with highway robbers.

The driver (Beibi Gong) of Bus with the number 44 stops the bus to pick up a young man (Chao Wu) on a deserted country road. The young man is grateful that the bus has arrived, and tries to flirt with the driver, but she soon tells him to sit down. After a while, the bus stops for two men (Qiang Li and Kui Zhou) in the road, one of whom appears unwell, but upon boarding it is revealed that they are actually robbers, and demand that the driver and passengers hand over all their money and valuables. When one passenger refuses despite the driver telling him just to hand the money over, the robbers beat him until he complies.

The robbers leave the bus with everyone’s money and valuables, but on the way out one of them stares at the driver, then drags her out of the bus and starts raping her in a bush. The young man then asks the passengers why they are all just sitting. One man starts getting up, but his wife grabs his arm and he sits back down. Eventually, the young man leaves the bus on his own to help the driver. The passengers all jump to the window to watch, but do not help. The young man gets into a fight with the other robber and is stabbed in the leg.

However, the robbers then flee, and the driver gets up and returns to the bus, blood on her face, the other passengers looking away when she gives them all a look of anger and disgust. She sits back down and takes a few moments to pull herself together. Shortly afterwards, the young man manages to return to the bus. She tells him to get off the bus. He protests that he was the only one who tried to save her, but she just shuts the door in his face and throws his bag out of the window before driving off.

Confused and dejected, the young man sits in the road, then later, we see him walking along the road towards where the bus went. He hitches a lift in a passing car, and is driven onwards. A police car overtakes, and soon they catch up with the police car by a bridge with smoke coming from down the embankment. An officer is shown on his radio, confirming that the driver and all passengers are dead. The young man looks dumbfounded for a while, then when he realises what has happened, the film ends as a slight smile appears on his face.

Having a concern for one’s neighbour is fundamental for human relations. Is it rapidly eroding in Sri Lankan society? Are we becoming frozen with regard to human sufferings? With the advancements of technology and upliftment of living, are we emerging as more self-centred and looking at my own interests?

Why it happens

According to Kendra Cherry, there are two major factors that contribute to the bystander effect. First, the presence of other people creates a diffusion of responsibility. Because there are other observers, individuals do not feel as much pressure to take action, since the responsibility to take action is thought to be shared among all of those present.

The second reason is the need to behave in correct and socially acceptable ways. When other observers fail to react, individuals often take this as a signal that a response is not needed or not appropriate. Other researchers have found that onlookers are less likely to intervene if the situation is ambiguous.

In the case of Kitty Genovese, many of the 38 witnesses reported that they believed that they were witnessing a “lover’s quarrel,” and did not realise that the young woman was actually being murdered.

Lessons for us

Sri Lanka is supposed to be more collectivistic compared to some western countries where the individualistic approach is the more dominant. There could also be a Sri Lankan twist to the whole issue, where the bystanders are aware of the consequents of harassment, waste of time, and even threats to their lives if they come forward.

There were encouraging responses in the recent past in this context. Police managed to arrest a couple of culprits based on timely tips by the “bystanders”, in stark contrast to the bystander effect. The challenge is to sustain such practices where a gradual decline of concern for others, fuelled by over–emphasis on materialistic gains is evident.

The practice of socio-cultural and religious values with regards to being concerned about ones’ neighbour is the vital need. It is for managers and others alike, a wakeup call to be more conscious about the fellow human beings.

The bystander effect essentially refers to the phenomenon in which the greater the number of people present, the less likely people are to help a person in distress. When an emergency situation occurs, observers are more likely to take action if there are few or no other witnesses.

Way forward

Having a concern for one’s neighbour is fundamental for human relations. Is it rapidly eroding in Sri Lankan society? Are we becoming frozen with regard to human sufferings? With the advancements of technology and upliftment of living, are we emerging as more self-centred and looking at my own interests? These could be some questions that are pertinent and demanding answers to be found collectively.

(Prof. Ajantha S. Dharmasiri can be reached through [email protected], [email protected] or www.ajanthadharmasiri.info)