Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Wednesday, 22 September 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Central Bank Governor Ajith Nivard Cabraal

|

The Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) has been subject to severe criticism over the rapid expansion of the money supply since last year. The aggregate money supply rose by 21% during the last 12 months. Currency held by the public, which is commonly known as money printing, rose by around 23% during this period. This was resulted from the continuous borrowings by the Government from the CBSL and commercial banks.

This trend would continue in the coming months unless the Government reduces its dependence on the banking sector to finance the budget deficit. Such possibility is rather remote, as there are hardly any other funding sources. Also, the CBSL is unlikely to reduce fiscal accommodation in the backdrop of political pressures.

CBSL Governor’s view on money supply and inflation unacceptable

The newly-appointed CBSL Governor Ajith Nivard Cabraal asserts that money printing has no impact on inflation, as reported in last Sunday’s ‘Divaina’ newspaper. He further stated that excess money issued can be absorbed by the CBSL whenever the need arises. This view involves at least two fundamental caveats.

First, the statement that there is no relationship between money printing and inflation contravenes basic economic principles. Irving Fisher (1867-1947) formalised the relationship between the two variables in terms of his ‘Quantity Theory of Money,’ which was further developed as Monetarism by Milton Friedman (1912-2006). Based on rigorous quantitative studies across the world, the bidirectional relationship between money supply and inflation is undeniable.

Second, the CBSL is not in a position to absorb excess liquidity whenever necessary as claimed by the Governor. The reason is that the CBSL continues to buy the unsold portion of Treasury bills and bonds directly from the primary auctions to fill the Government coffers, instead of selling such securities through open market operations for mopping up excess liquidity.

CBSL’s holdings of Government securities rising

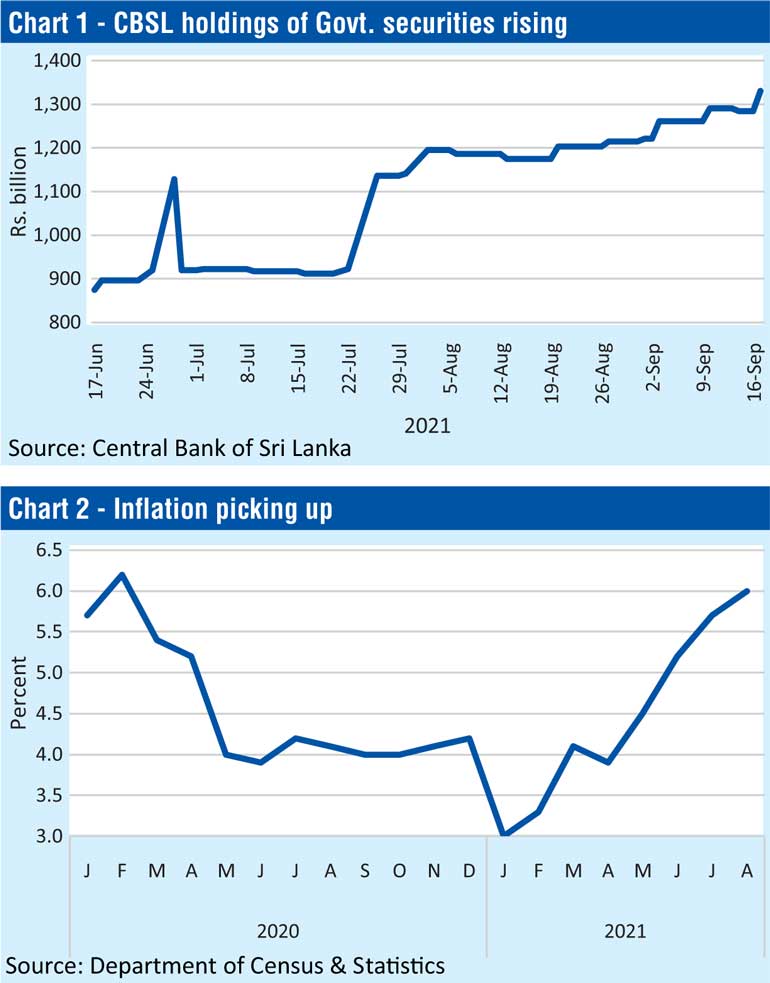

Continuous lending to the Government by CBSL has resulted in a substantial increase in its holdings of Treasury bills and bonds. Such holdings rose by 52% from Rs. 874 billion to Rs. 1,330 billion during the last 3 months (Chart 1).

As a result, the CBSL had to drop one of its key monetary policy instruments, i.e. open market operations (OMO). The CBSL can usually adopt OMO to mop up any excess liquidity in the market by selling its government securities, and vice-versa. There is less market demand for such securities due to their low yield rates, and therefore, CBSL is unable to sell them for contractionary monetary policy purposes even if it wants to do so, as mentioned above.

There are constraints to foreign borrowings as reflected in heavy under-subscriptions of international sovereign bonds in the recent auctions. Even the local Treasury bill and bond auctions have been heavily undersubscribed due to their unattractive yield rates. For example, the Treasury bill auction held last week was undersubscribed to the extent of 50%. The rest of the Treasury bills had to be purchased by the CBSL to meet fiscal needs causing a rise in its holdings of Government securities and currency issues. This has been the practice in recent months.

Is money printing the right treatment for the ailing economy?

Governor Cabraal, in his previous capacity as a State Minister, strongly advocated money printing for the revival of the pandemic-hit economy. In an interview with the Daily Mirror last month, he mentioned that money printing is just like a drastic treatment prescribed by a doctor to a major illness (https://www.dailymirror.lk/hard-talk/Money-printing-is-like-drastic-treatment-to-a-major-illness-Ajith-Nivard-Cabraal/334-217302).

He further said that money printing leads to inflation only during normal times. As there is a contraction of the economy at present, the risk of occurring inflation as a result of money printing is much less. Once the economy gets back to normalcy, you have to pull it back, according to him.

He also reiterated in several forums that the Government can resolve the debt problem without resorting to the IMF.

It should be noted here that the money printing was not due to the pandemic but it was an outcome of the Government borrowings from the banking sector to finance the budget deficit. The excessive money growth resulted from increased bank lending to the Government led to exert demand pressures on the domestic market and imports, thereby causing inflation, foreign trade imbalance, and rupee deterioration, quite contrary to Cabraal’s claims. The annual inflation, measured in terms of the Colombo Consumer Price Index (CCPI) has gone up to 6% by now, as shown in Chart 2.

It is impossible to contract the money supply in the current inflationary situation, as argued by Cabraal since the banking sector will have to continue lending to the Government to meet its revenue shortfalls, caused by drastic tax cuts implemented last year.

Contrary to Cabraal’s advocacy, money printing is a wrong treatment to the ailing economy that might lead even to kill the patient, as I pointed out in this column last month (https://www.ft.lk/opinion/Rupee-under-stress-as-trade-deficit-expands/14-721803). The money creation will only aggravate economic sickness by widening the trade deficit and accelerating inflation.

CBSL lost market-based monetary tools

The CBSL reformulated its monetary policy in the 1980s and 1990s by moving away from direct controls to market-based tools to be aligned with the liberalised economic environment. It gradually eliminated credit controls and overall credit ceilings. Eventually, the open market operations and policy interest rates along with a flexible exchange rate system became the key monetary policy tools.

The recently-introduced direct monetary controls including interest rate caps, credit ceilings, exchange rate fixing, and forex regulations reflect a reversal of market-based monetary policy. They have adverse effects on free-market activity, as already reflected in inflationary pressures, commodity shortages, undersubscribed Government securities, foreign exchange depletion, and exchange rate distortions.

Inflation targeting monetary policy abandoned

The previous Government envisaged implementing flexible inflation targeting monetary policy framework by 2020 under the Extended Fund Facility (EFF) with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). For this purpose, the now-abandoned Central Bank Bill was to be approved by the Parliament to replace the present Monetary Law Act.

Inflation targeting is a monetary policy strategy under which a country’s central bank aims to keep a pre-announced inflation rate over a specific time frame. Transparency and accountability are two essential components of inflation targeting. Transparency implies that the central bank should convey the inflation target with justification through public announcements. Accountability means that the central bank should not miss the inflation target.

Inflation targeting monetary policy would have provided greater independence to the CBSL shielding itself from political pressures to conduct monetary policy targeting its core objective of price stability. These initiatives were abolished by the present regime. Hence, the CBSL Governor continues to enjoy the luxury of implementing any harmful monetary policy measures without any transparency or accountability.

Independent central banking vital

The policy space available to CBSL in conducting independent monetary policy is severely restricted by the fiscal dominance, as I discussed in the last week’s FT column (https://www.ft.lk/opinion/Distancing-the-Central-Bank-from-politics-vital-for-economic-stability/14-723012).

The fiscal deficit running over 12% of GDP at present will continue to remain high with mounting debt commitments in the coming years. The persistent fiscal deficit demotivates CBSL to adopt a flexible interest rate policy stance, while inflationary pressures and the mounting external debt commitments restrict its ability to maintain exchange rate flexibility. In effect, the monetary policy has become inactive by now.

In the circumstances, the present monetary expansion along with direct credit and exchange controls will continue to prevail in the coming months causing detrimental effects on price and financial stability, as already evident from market tensions.

The capacity of the CBSL to reactivate market-based monetary policy for economic stabilisation purposes depends on its strength to diffuse political pressures that urge for monetary expansion. This would be an impossible task as long as the CBSL’s leadership is subservient to political masters.

(The writer is Emeritus Professor of Economics at the Open University of Sri Lanka and a former Director of Statistics, Central Bank of Sri Lanka, reachable at [email protected])