Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday Feb 13, 2026

Saturday, 27 June 2020 00:02 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

All serious wildlife enthusiasts have had, at one time or another, the experience of being charged down by an enraged wild elephant in the national parks. It is a most frightening experience to have a four-tonne giant bearing down at you. Sometimes this ends in calamity, although most often, if handled well, the event can be circumvented without major problems.

All serious wildlife enthusiasts have had, at one time or another, the experience of being charged down by an enraged wild elephant in the national parks. It is a most frightening experience to have a four-tonne giant bearing down at you. Sometimes this ends in calamity, although most often, if handled well, the event can be circumvented without major problems.

Wild elephants can be very dangerous. However much one is careful, and takes all possible precautions to avoid confrontations with these giants in the wild, there is always the possibility that things can turn nasty.

However elephants, and wildlife in general, are generally wary of humans and will give us a wide berth most often. In the wildlife parks, elephants have got somewhat accustomed to jeeps and human presence and closer interactions are possible at most times.

Deterring a charging elephant

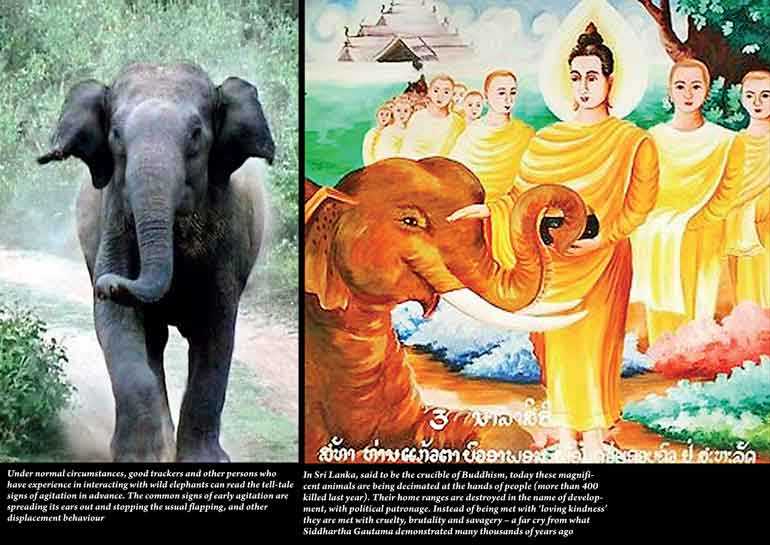

Under normal circumstances, good trackers and other persons who have experience in interacting with wild elephants can read the tell-tale signs of agitation in advance.

The common signs of early agitation are spreading its ears out and stopping the usual flapping, and other displacement behaviour such as breaking off nearby braches, scooping dust and throwing it over the back, and even a few mock threatening lunges, with vigorous shaking of the head from side to side.

Now there are numerous stories (many bordering on folklore) about certain methods that can be used to deter a charging elephant. There are senior trackers (a fast dying out breed) who swear by specific charms and rituals that can stop a charging elephant.

I personally have not witnessed any of these methods in practical use, although I have heard very reliable testimonies about such incidents where angry elephants at full charge have been stopped dead in their tracks.

P.E.R. Deraniayagala, former Director of National Museums in Sri Lanka, who has done extensive studies in the mid-1900s on elephants, has listed some of these chants (Gaja Angama) in studies published in 1955.

What I personally believe is that it is a physiological battle between the elephant and man during such confrontations. Deep down instinctively the elephant fears man. So what needs to be done under such circumstances is not to show fear, but to show strength, confidence and calmness.

I am a firm believer in inner dialogues with elephants, reaching out to their ‘sixth sense’. I have personal experiences where an angry elephant has most often reacted positively to calmness, kindness and empathy. Elephants are remarkably intelligent animals, and can understand such emotions.

It is because of this belief that I recently revisited the story of the Buddha and enraged elephant Nalagiri.

The Buddha and Nalagiri, the elephant

Extract from Pāli Vinaya, II, p. 194–196:

In Rājagṛhā at that time there was the fierce elephant Nālāgiri, and a killer of men (manussaghātaka). Devadatta ( an estranged cousin of the Buddha ) went to find its mahouts and, taking advantage of his influence over king Ajātaśatru, ordered them to let loose the animal against the Buddha when the latter entered Rājagṛha.

The next day, surrounded by many monks, the Buddha came to the city on the usual pindapatha (means literally “placing of food in a bowl” a custom where Buddhist monks go around receiving food as alms). The elephant was unleashed and, with its trunk erect, ears and tail rigid, rushed against the Buddha. The monks begged the Buddha to go back, but the latter reassured them that no aggression coming from the exterior could deprive him of his life.

Frightened, the population of Rājagṛha took refuge on the roof-tops and made wagers as to who would win, the Buddha or the elephant.

Then the Buddha penetrated Nālāgiri’s with a mind of loving-kindness (Nālāgiriṃmettena cittena phari) and, lowering its trunk , the animal stopped in front of the Buddha who caressed its forehead with his right hand (dakkhiṇena hatthena hatthissa kumbhaṃ parāmasanto), saying:

“O elephant, this attack would be shameful. Flee from drunkenness and laziness; the lazy miss the good destinies. Act in such a way as to attain a good destiny.”

At these words, Nālāgiri gathered the sand-grains covering the feet of the Buddha in his trunk and spread them on top of its head; then, still kneeling, it backed away, always keeping the Buddha in sight.

It was on this occasion that the people chanted the following stanza

“Some tame them with blows of the stick, with pitchforks or with whips;

With neither stick nor weapon was the elephant tamed by the Great Sage”

It is interesting to note here that the Buddha used empathy and calmness first, and reached out with loving kindness to the enraged animal. No doubt that the animal sensed these energy forces being emanated by this serene and holy man.

This is exactly what I was eluding to earlier. If you are pure of mind, and seek to enjoy the wonders of nature and its flora and fauna, not for entertainment, but to celebrate in the wonders of the natural environment, I truly believe that very little harm can befall you.

On many occasions when confronted with difficult situations in wildlife parks with elephants, my family and I have always used inner dialogues such as “we are here not to harm you, but to watch you and understand your beauty and majesty”. Most often they have worked.

Conclusion

In Sri Lanka, said to be the crucible of Buddhism, today these magnificent animals are being decimated at the hands of people (more than 400 killed last year). Their home ranges are destroyed in the name of development, with political patronage.

With shrinking habitat, and less access to food, the remaining wild elephants of Sri Lanka are forced to confront humans. Instead of being met with ‘loving kindness’ they are met with cruelty, brutality and savagery, further aggravating the confrontation, a far cry from what Siddhartha Gautama demonstrated many thousands of years ago.