Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Wednesday, 31 March 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

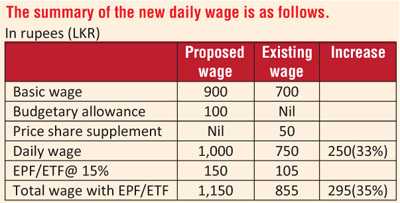

The Government officially announced by its Gazette dated 5 March that as per the wages board decision, the estate workers' daily wages will be Rs. 1,000. That was an unprecedented move as it was the first time the Government's intervention determined the daily wage – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

Imagine an industry group that has made revenue to the tune of Rs. 300 billion for the last five years but not been able to record at least 1% of that revenue as net income. Imagine an industry group that has recorded losses in all but one year for the last five years. Imagine an industry group that has accumulated losses to the tune of Rs. 10 billion for the previous five years.

Imagine an industry group that has made revenue to the tune of Rs. 300 billion for the last five years but not been able to record at least 1% of that revenue as net income. Imagine an industry group that has recorded losses in all but one year for the last five years. Imagine an industry group that has accumulated losses to the tune of Rs. 10 billion for the previous five years.

That is Sri Lanka's regional plantation companies (RPCs) scorecard for the past five years. Sri Lanka's plantation industry has now reached a critical juncture with the recent government-imposing a daily wage of Rs. 1,000 for estate workers.

Industry experts are seriously worried that it will be a fatal blow to the RPC industry subgroup. RPCs have objected to the wage increase because it was not productivity-based but an attendance-based wage, increasing financial losses and jeopardising the industry's sustainability.

The Government officially announced by its Gazette dated 5 March that as per the wages board decision, the estate workers' daily wages will be Rs. 1,000. That was an unprecedented move as it was the first time the Government's intervention determined the daily wage. First offered as an election pledge in the Presidential and General Elections, it was subsequently included as a Government Budget proposal last November. Hence, the Government intervention was a politically motivated move to fulfil its election pledge rather than to facilitate the collective bargaining process between the RPCs and the trade unions (TUs).

RPCs, which account for up to 40% of the total tea production, 35% of the rubber and 10% of coconut, must grapple with volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity (VUCA) in the operating environment. The VUCA factors have increased the likelihood of business failure for RPCs, especially in this age of digital disruption, climate change and an outbreak of COVID 19. Industry experts have warned that the new wage increase would be the tipping point of the industry's collapse.

As a Chartered Accountant employed in the industry for the past eight years, the writer wishes to check whether RPCs would pay the extra wages without running into financial difficulties from a financial and analytical perspective. Hence the intention is to do a reality check of the RPCs ability to pay the extra wage. This piece will also supplement two previous columns on the subject published on the Daily FT by J. A. A. S. Ranasinghe and Gotabaya Dasanayake on 12 March and 1 March, respectively. Before we move on to the analysis, let us answer an important question.

Do estate workers deserve Rs. 1,000?

It is highly desirable if the estate workers can earn a daily wage of Rs. 1,000. If they find work outside the plantations, they would easily make this amount. For example, if a male worker works on a construction site, he can earn at least Rs. 1,500 daily. Hence, they will always be lured by the opportunities outside the estate and ponder why they can't get at least Rs. 1,000 from the estate work they do. That is a key reason why workers migrate out of the plantations causing severe labour shortages for the estates. The new generation of the worker community prefers to leave the estates and find better employment opportunities elsewhere.

Workers have to toil in the difficult terrains under harsh conditions withering in the sun, rain, cold, leech and wasp attacks and even snake bites. Hence, we should empathise with them and acknowledge their contributions to the industry. Also, they deserve a decent life and better living conditions. Moreover, they have found it challenging to maintain a decent living standard due to the soaring cost of living over the years.

Further, as citizens of a modern world, they also have to adapt to modern needs such as laptops, smartphones, the internet and other comforts. They have to spend on children's education so that their offspring will find better opportunities outside the plantations. Therefore, there have been an evolution and a change in their needs that rationalise the demand for Rs. 1,000.

Thus all stakeholders would agree that workers deserve a daily wage of Rs. 1,000, which is the minimum amount to entice them to remain in the plantations. Further, new wage can be a morale booster for the workers and restore their dignity of labour. Therefore, as far as the workers are concerned, the daily wage of Rs. 1,000 is reasonable. However, we all must understand that everything in life is a trade-off. Simply put, you can excel in education only by studying hard and get higher pay only by working hard and contributing more.

What was the RPCs’ proposal?

RPCs, in the recently concluded wage negotiations, proposed a wage model aimed at increasing productivity, which TUs should have accepted as a model that could create a win-win case for both parties. Under the RPCs proposals, a fixed daily wage model would have been applicable three days a week. On the rest, workers were to be remunerated based on one of two productivity-linked earning models – one where workers will earn Rs. 50 for every kilo of tea leaves plucked, the other being the revenue share model where workers can become entrepreneurs.

However, TUs rejected it, claiming that Rs. 1,000 was a longstanding and non-negotiable demand. The Government had endorsed it by including it as a Budget proposal in the last Budget. We should also bear in mind that Sri Lanka is the highest in wages to total production cost, and the new wage will further exacerbate that ratio.

Impact of the wage hike on RPCs

Impact of the wage hike on RPCs

It is estimated that RPCs would need at least Rs. 12 billion extra cash per annum to meet the new wage bill based on the active labour force on the RPC estates. Each RPC will have a different figure depending on its labour force and labour outturns. Accordingly, one RPC would need an additional Rs. 545 million per annum on average and Rs. 45 million a month. Therefore, we can reasonably and pragmatically conclude that a typical RPC would bear an extra cost of Rs. 400 to 500 million a year. Accordingly, there must be an increase in revenue to the tune of Rs. 400 to 500 million to meet the obligation, which will only be a herculean task for any RPC.

The total impact will be even higher when the gratuity impact is taken into account. There will be a higher charge in the income statement because of the provision for gratuity, which will further dilute profitability. The provision will materialise when workers claim it on their retirement, based on Rs. 1,000. Moreover, maternity benefits, holiday pay and other benefits will invariably increase proportionately.

Basis of financial analysis

This financial analysis is based on the financial results of 19 RPCs listed on the Colombo Stock Exchange (CSE), which have been published in their annual reports on the CSE website. The period covered is from the financial year FY2015/2016 to FY2019/20 (from 1 April 2015 to 31 March 2020), covering five financial years.

For those few RPCs whose financial year runs from January to December, the period is the same as 2015 to 2019. Currently, there are 23 RPCs, but four of them are excluded from this analysis due to various reasons. Two of the RPCs are State-owned – namely, Kurunegala Plantations Ltd. and Chilaw Plantations Ltd., which are not listed in the CSE. Hence, they are excluded due to the absence of published financial statements for the analysis.

Similarly, Pussellawa Plantations Ltd. is also excluded as it is not listed on the CSE. Further, Watawala Plantations PLC is scoped out as it is an exclusive oil palm plantation company, in contrast to the rest of the RPCs, which are multi-crop plantations comprised of tea and rubber coconut, oil palm and other crops.

Moreover, the business model and the oil palm plantation's operating environment are different from those of the other plantations; hence, there is no comparability. The information is presented using charts with explanations and interpretations for the reader's comprehension.

Analysis of RPC subgroup profitability from FY2016 to FY2020

Strong topline (revenue) but negative bottom line (profitability).

Chart 1: Annual revenue and profit/loss (Figures are in LKR millions)

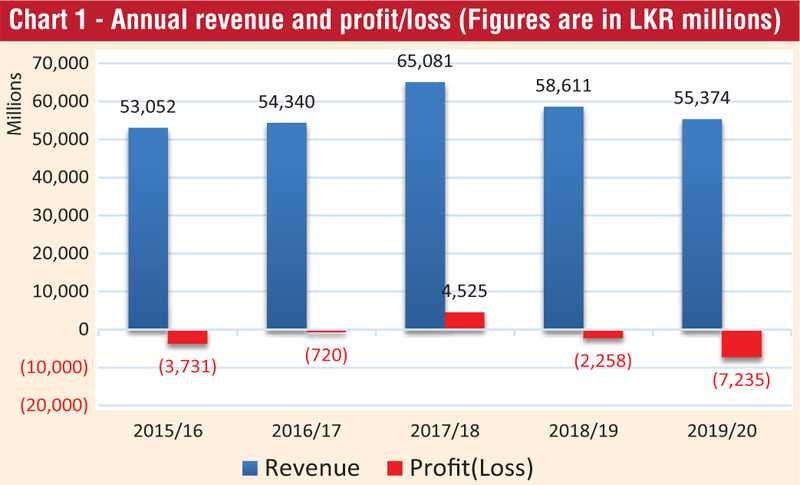

Revenue and the profitability of the 19 RPCs for the five years ended 31 March 2020 is analysed and shown in Chart 1 above. We can notice that revenue for FY2015/16 was Rs. 53 billion, which peaked in FY2017/18 to Rs. 65 billion and ended with Rs. 55.3 billion for FY2019/20.

Nevertheless, the RPC subgroup made losses in all years except in FY2017/18. The first year's loss was Rs. 3.7 billion; Rs. 7.2 billion for the year ended 31 March 2020. The profit during FY2017/18, which was exceptional, was due to the higher auction prices for tea that prevailed throughout that year.

It illustrates that when the markets are depressed for tea and rubber, the RPCs are bound to suffer losses and return to profitability when they rebounded, which underscores that RPCs have no control over their primary commodities' market price, i.e. black tea and latex.

The magnitude of the losses suffered by the RPCs substantiates their claim that the new wage is not affordable. That should be an eye-opener for the trade unions and the Government, who insist that RPCs are profitable and will have no issue paying the new wage. You should also note that accumulated losses have already depleted the liquidity (cash reserves) as well. As a result, the operations are funded by working capital loans rather than by the operations' money.

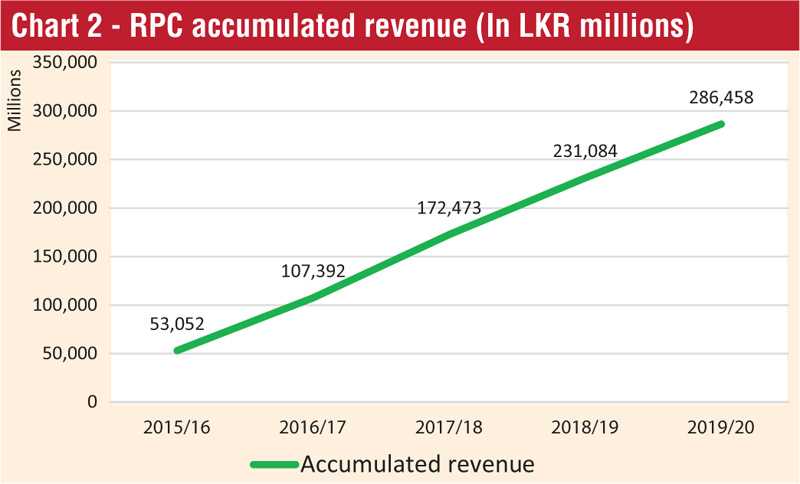

What about accumulated revenue and losses?

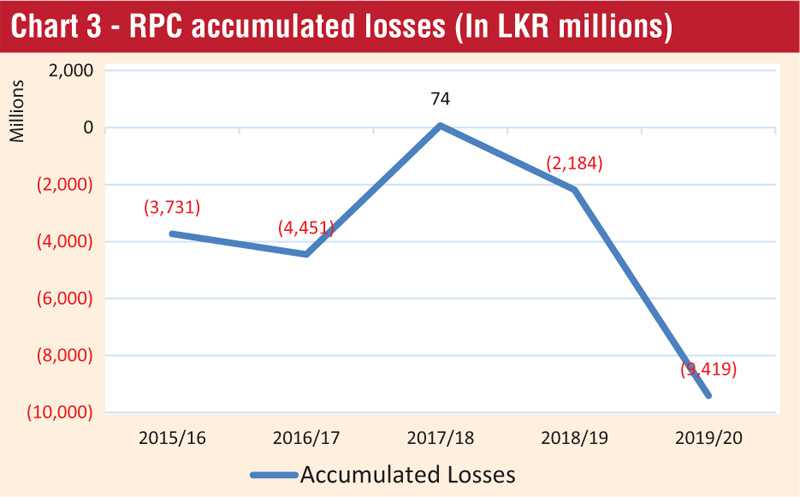

Chart 2 shows that RPCs have accumulated total revenue of Rs. 286 billion for the five years under review. This measure is mainly used to compare the RPC subgroup's revenue for the last five years with the accumulated profit or loss. When Chart 2 and 3 are reviewed in tandem, you can see the RPC subgroup's earning capacity over the five years. You should notice that RPCs have accumulated a whopping loss of Rs. 9.4 Billion for the five years under review.

That should be alarming, as it is highly doubtful whether there is any other industry subgroup in the Colombo Stock Exchange which has incurred similar losses for the last five years. That highlights the plantation industry's vulnerability to volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity in the micro and macro operating environments.

As a price taker, the RPC subgroup has no control over the market factors and survives at these forces' mercy. The future looks pretty bleak for the RPCs when they have made such a colossal loss over the past five years. The question that begs an answer is how RPCs can bear Rs. 12 billion in one year on the extra wages which is greater than the cumulative losses they made for the last five years.

Not all RPCs run at a loss, there are profitable RPCs as well.

Chart 4: Profit and losses of RPCs (In LKR millions)

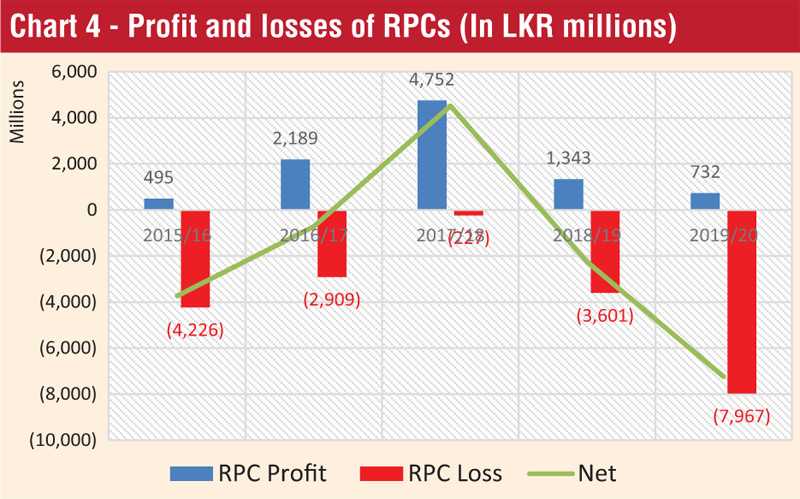

You may get the wrong impression when reading Chart 1-3 that all 19 RPCs have made losses. However, there are profitable RPCs as well as in any other industry. As illustrated in Chart 4 above, the profit made by RPCs are presented in the blue colour columns, and the red columns present losses. What should be noted is that the losses are always greater, nullifying any profit in all years except FY2017/18. The green colour line represents the net profit or (loss) when these two combined.

How many RPCs have made losses and how many made a profit?

How many RPCs have made losses and how many made a profit?

As we have noted already, not all RPCs are run at a loss. Thus we need to figure out how many RPCs were profitable and how many of them made losses during the five years under review. Chart 5 shows that 13 RPCs have accumulated losses (individually), and only six have accumulated profit, which underscores the fact that most RPCs are not performing well. These RPCs will be very vulnerable to the wage impact.

Key insights on loss-makers

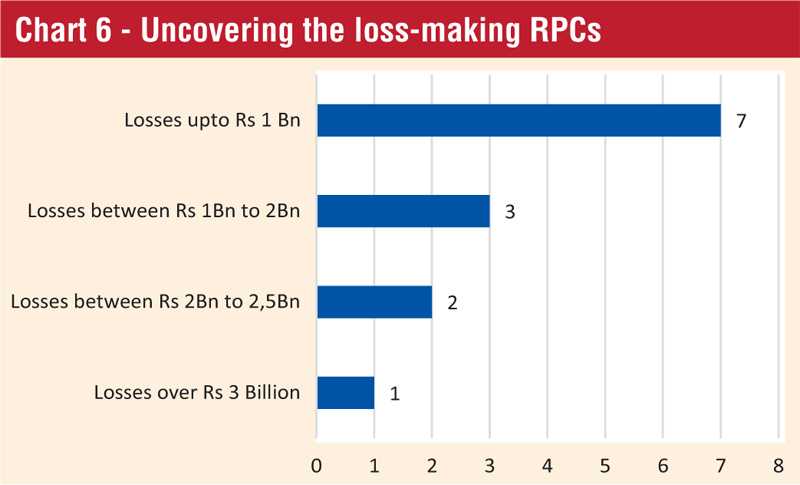

Chart 6 gives us some startling revelations into the accumulated loss-makers in the RPC subgroup for the five years under review. According to the chart above, one RPC has accumulated a loss of over Rs. 3.8 billion, and two RPCs have accumulated losses ranging from Rs. 2.5 to 2.8 billion (individually). Three RPCs (individually) have accumulated losses just under Rs. 2 billion, and seven RPCs (individually) have accumulated losses up to Rs. 1 billion. You can notice in their respective financial position statements (published on CSE) that these losses have eroded the shareholder's funds (capital base) of those RPCs.

The implications are very alarming as there is a high likelihood that the top six loss-making RPCs will go out of business sooner than later due to the new wage burden. The accumulated losses have already taken a heavy toll on their cash reserves, and the extra wage cost would be quite unbearable and serve a fatal blow.

Are profitable RPCs sustainable in the face of the wage hike?

Are profitable RPCs sustainable in the face of the wage hike?

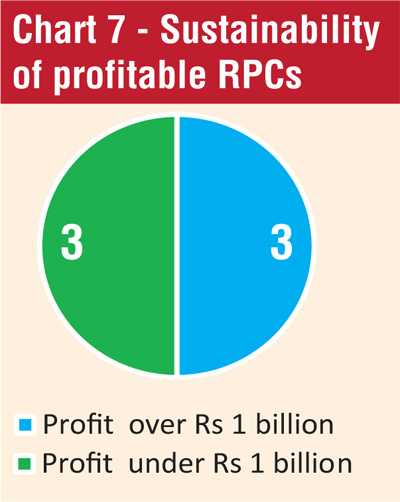

As revealed already, only 6 RPCs have accumulated profit for the five years under review. Can they absorb the increased wage cost mandated by the wage board? Let us explore. As depicted in Chart 7, only three companies (individually) have accumulated profit of more than Rs. 1 billion. However, it should be noted that their accumulated profits do not exceed Rs. 2 billion.

The rest of the three profit-making RPCs (individually) have accumulated less than Rs. 1 billion for the five years. These reveal that even these ‘good’ RPCs will struggle in the face of the extra wage burden, and their business risk will further increase.

Can the Government take over the plantations?

Several Ministers of the Government had threatened to take over the plantations, especially when there was a deadlock in the recent wage negotiations. This threat is repeated by the politicians whenever there is an unresolved dispute between the Government and the RPCs. Yes, the Government can take over the plantations anytime by purchasing all or majority shares of the RPCs listed on the CSE, which will cost the Government a colossal amount of rupees.

The Government will not have money for such a move. Even if it succeeds in purchasing and taking over, it will soon be disastrous for the Government under the present economic conditions. As the Government is already cash-strapped, the Treasury will not pay the workers wages on the due dates. So those threats were deemed empty as no sane government would want to go back to square one, i.e. nationalised era before 1992.

However, the Government will pursue a restructuring agenda to turnaround the loss-making RPCs, including change of ownership of those RPCs. Towards this end, the previous Government in 2017 conducted an evaluation and a review of the RPCs’ performance since the privatisation. Several reputed audit firms were commissioned to carry out this evaluation.

RPCs were required to provide various operational and financial data since the privatisation in 1992, which was a daunting task due to retrieving the old data. However, nobody is aware of follow-up actions or policy decisions that were taken afterwards. The current Government can refer to those reports (available with the Treasury or PMMD – Ministry of Plantations) to understand the RPC performance instead of spending on new studies.

Conclusion

Although there is a consensus that estate workers should get a daily wage of Rs. 1,000, the preceding analysis strongly indicates that all RPCs would run into serious financial difficulties in making the extra wage payment. The new wage will spell doom for the RPCs unless there is a turnaround in the market, ground and climatic/weather conditions favouring the RPCs, such as sufficiently higher auction prices (this is the key to the turnaround), increase in the output and yields with the workers' collaboration. Some RPCs will face severe financial distress immediately, and the risk of bankruptcy will loom large for them. Some RPCs will struggle for some time, but they will see the twilight in due course. Only a few RPCs will survive despite being crippled and bleeding.

In essence, the sustainability of the RPC subgroup will be at stake. Therefore, the plantation industry, which is more than 150 years old, needs a turnaround strategy with all the stakeholders' participation to uplift its competitiveness and sustainability on par with the world standards.

(The writer is a Chartered Accountant with nearly two decades of local and foreign experience. The views expressed here are strictly personal and do not represent any company or association. He can be reached via his LinkedIn page.)