Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Friday, 26 June 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The crisis

The COVID-19 pandemic has created chaos with the socio-economic, political, religious, and financial structures of the entire world as never before. The world’s top economies such as the US, China, UK, Germany, France, Italy, Japan are on the verge of collapse. Stock markets around the world have been pounded and oil prices have fallen off a cliff. In the current situation, most of the investors are removing its funding from multiple businesses and in this regard $ 83 billion has already removed from emerging markets since the outbreak of COVID-19.

Germany, France, Italy, Japan are on the verge of collapse. Stock markets around the world have been pounded and oil prices have fallen off a cliff. In the current situation, most of the investors are removing its funding from multiple businesses and in this regard $ 83 billion has already removed from emerging markets since the outbreak of COVID-19.

The jobs of common people are running a real threat of loss due to business shutting down and companies will be unable to pay to workers, resulting in lay off of employees. So, the impact of Covid-19 is severe on the economic structure of the world. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), global growth could go down to 1.5% in 2020 which is half of the previously forecasted rate if the virus continues to spread.

Economic activity in the South Asian region is projected to contract by 2.7% in 2020 while the global economy is expected to shrink by 5.2% according to the World Bank as pandemic mitigation measures hinder consumption and services activity and as uncertainty about the course of the pandemic chills private investment. Foreign Direct Investment flows could fall from 5 to 15%. The most affected and vulnerable sectors would be tourism and travel-related industries, hotels, restaurants, sports events, consumer electronics, financial markets, transportation, and overload of health systems.

The impact of all these will be very badly felt on our tiny economy in all fronts being an economy that earns 14% of total foreign exchange earnings from tourism with a population of 6.7% below the poverty line and an ailing export sector with a huge trade deficit. One of the most challenging tasks to be faced by the Government would be also to avert the extra-large number of citizens who are likely to fall below the poverty line due to the loss of jobs in the Middle East, tourism, apparel industries. This is where Microfinance can step in to show its’ value as a strategy for mitigating the negative impact of COVID and the Sri Lankan Government should not miss out on this opportunity to garner the support of the microfinance sector.

The role of microfinance?

Microfinance provides small business loans to lower-income communities, to support economic development through enhanced entrepreneurial activity through both financial and non-financial assistance to low-income groups.

Microfinance services are recognised as one of the key development strategies for alleviating poverty through social and economic development with special emphasis on empowering women. There are two main approaches in offering microfinance services to lower-income earners; the poverty lending approach, which promotes donor-funded credit for the poor taking the approach of reducing poverty through subsidised and charitable non-finance methods and the financial system approach, which advocates commercial microfinance for economically active poor.

The primary goal of both approaches is the same, however, research findings show that large-scale sustainable microfinance services can be maintained only through the financial system. Hence the microfinance institutions (MFIs) have emerged to address the market needs of the economically active low-income groups, who have been pushed out of the formal financial sector. The “economically active low-income people” generally refer to those among the poor who have some form of employment who are not starving nor destitute.

By addressing this gap in the market sustainably, MFIs have become part of the formal financial system of developing countries. According to this definition, microfinance encompasses the provision of other financial services such as savings, insurance, money transfers, payments, and others such as business advisory services.

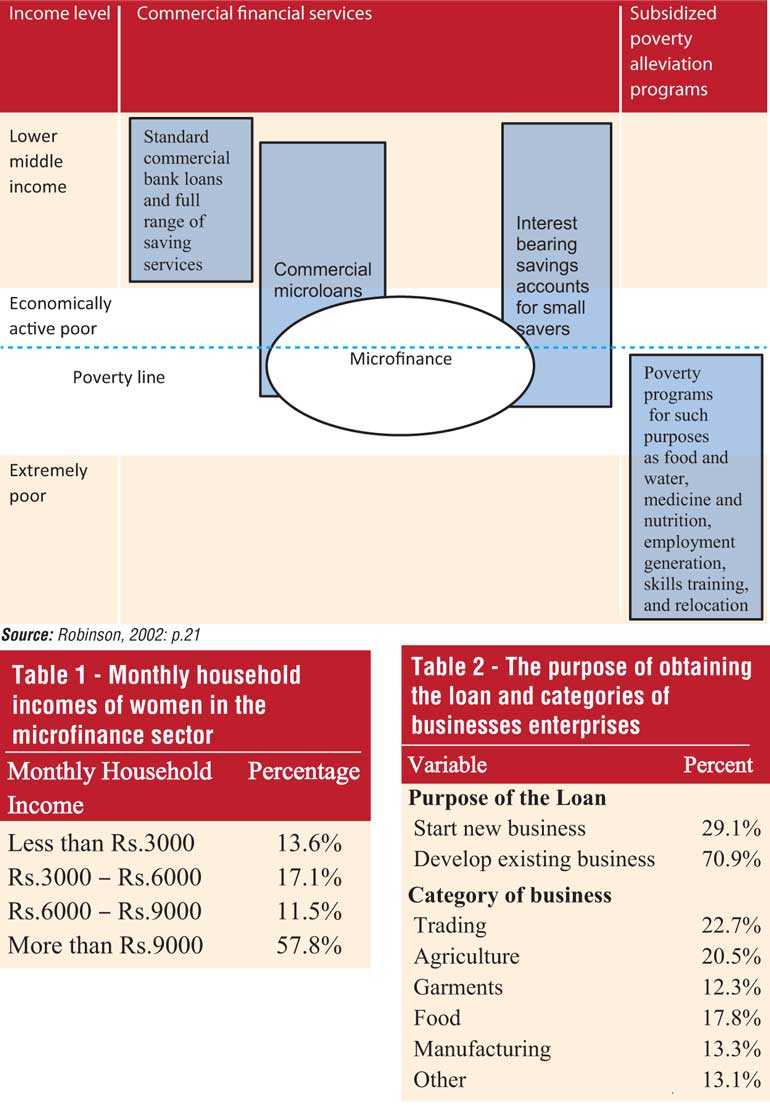

However, the practitioners and researchers hold diverse views on microfinance, its range of services, and its target recipients. At the outset, it is imperative to get a clear idea as to where the target population of microfinance clients exists, in a broader context. The figure below displays the financial services in the poverty alleviation toolbox; the third column shows nonfinancial poverty alleviation tools that are suitable for those below the poverty line and essential for the extremely poor.

Hence, the tools shown in the third column are funded by direct subsidies or grants. Microfinance offers services to the economically active poor to promote entrepreneurial activity on a commercial basis. Therefore, the target population of a group of microfinance clients is shown in the figure who belong to economically active and lower-income categories.

The microfinance revolution

The concept of special MFIs was established specifically for the poor of society, not very long ago. After the Second World War and into the 1970s, development finance institutions were not particularly concerned about poor target groups of customers.

However, this view shifted after the realisation of the fact that massive amounts of foreign funds invested in large projects did not necessarily lead to the "trickledown effect” which had been expected. The micro-finance movement exploited new contractual structures and organisational forms that reduced the riskiness and costs of making small, un-collateralised, and cheap loans. Though, the critiques argue that financing schemes proved extremely costly for donors and, at least in some cases, for the borrowers as well (due to high transaction costs); that they inevitably failed to reach many members of their target groups.

However, the researchers have argued that microfinance, and the impact it has, go beyond just business loans. The poor use of financial services, not only for business investment in their microenterprises but also in health and education, to manage household emergencies and to meet a wide variety of other cash needs that they might encounter.

Furthermore, many microfinance programs have targeted women (who are the poorest of the poor) as clients and bridged gender disparity. This has not only helped empower women who appear more responsible and show a better repayment performance, but also shown that women are more likely to invest increased income in the household and family well-being.

Microfinance, therefore, acts not only as an economic stimulator for small enterprises but also has far-reaching social impacts. This lead to the microfinance revolution, when formal financial institutions such as banks and non-bank financial institutions are looking for rich customers who have the collateral, MFIs are targeting poor clients to fund their entrepreneurial activities.

The literature suggests that the nature of microfinance is complex and in practice often little understood, especially when it comes to problems arising from a conflict of interests between the parties involved in the process. The mainstream lack of knowledge on how and at whom these programs are aimed has resulted in many factors not taken into consideration while launching such programs in their Preparatory Assistance Phases (PAPs).

Furthermore, the question which is usually left out of the whole set up is through whom to mobilise the credit for the poor who have no access to it. It is therefore extremely important to devise and construct programs by taking into consideration three components, namely, environments (economic, social, and political), role players, and stakeholders.

Prof. Mohammed Yunus’s (the founder of Grameen Bank and pioneering the concepts of microcredit and microfinance and Nobel Prize winner) ideas and findings on microfinance have been accepted worldwide, there are still some financial institutions which are reluctant to lend to the poor who have little or no collateral to offer in mitigating the risk of repayment of these loans. Hence, microfinance has prompted international research, which seeks to understand the operations and impact of institutions that focus on lending to the poor.

However, Prof. Yunus argues that the poor are the most suitable recipients of these small loans this view has been upheld by many researchers who argue that poverty and desperation of households make them a prime market for microfinance services. These scholars further highlight the fact that the poor are a prime market for credit services because of their liquidity needs for either entrepreneurial activities or consumption smoothing. However, to reach economically poor with financial services MFIs require innovative strategies accordingly unconventional lender can do so yielding repayment rates that are significantly higher than for such loans by formal lending institutions such as banks.

Joint Liability Lending (JLL) could be considered as one new approach to lending by MFIs. The economists in analysing JLL, focus on either the effects of joint liability on the behaviour of borrowers or on the fact that lending to groups is a way to reduce the cost of transactions as opposed to lending to individuals. This could be considered the “microfinance revolution”.

The demand for microfinance

According to the available literature, microfinance is conceptually unique everywhere in the world. However, it is also clear that practices and implementation programs that have been successful in a certain country should not necessarily be equally successful in another country. In this respect, the application of the “Grameen” concept introduced by Prof. Yunus in 1976 in Bangladesh may not necessarily be effective in Sri Lanka or any other country for that matter. This may be due to differences among these countries in their socio-economic conditions and ground situation.

The Asian Development Outlook (2019 ) reports that only in the Asian and Pacific region, approximately 1.2 billion people in about 240 million households are below the poverty line. More than 890 million of these poor people live in rural areas and most of them rely on secondary occupations, as agriculture alone is not enough to provide for their growing needs. This includes a whole range of paid employment, from micro-enterprises over services such as carpenters and weavers to self-employed businesses such as food stalls, tailoring, and shoe repair to mention a few. Again the operators of many of these micro-enterprises are women, who suffer disproportionately from poverty.

According to the National Women’s Law Center, (2016) the poverty rate for women worldwide was 14.5 percent in 2013 and has increased to 14.7 in 2014. Further NWLC data in 2015 confirms that women’s poverty rates are once again substantially higher than that for men with women working full-time year-round is paid only 79 cents for every USD paid for men. According to the Department of Census and Statistics (2017) of Sri Lanka, the population below the poverty line in Sri Lanka is 6.7%. According to this survey, the percentage of households below the poverty line in Sri Lanka was 5.3%. This implies that a larger percentage of women population exists in Sri Lanka than the average percentage of women in the world, who can be considered for microfinance.

The microfinance services are now widely available in Sri Lanka through public, private, and non-governmental institutions in rural areas and urban neighbourhoods mainly of low income. microfinance sector. Sri Lanka has a long history of microfinance. ‘Cheetu’ in Sri Lanka, operating at least since the early 20th century, is an informal but effective way of savings and capital accumulation, and therefore, functions as a basic method of microfinance for the poor.

The beginning of the microfinance movement in Sri Lanka dates back to 1906, under the British Colonial administration, with the Thrift and Credit Co-operative Societies (TCCS) under the Co-operative Societies Ordinance of Sri Lanka. In late 1980 a program known as “Janasaviya” (meaning, the strength of the people) was introduced by the Government of Sri Lanka to alleviate poverty which was renamed to “Samurdhi” in the early 1990s.

The interest for microfinance in Sri Lanka has increased considerably since the early 1980s, mainly due to the success stories of microfinance experienced by our neighbouring countries in the region, especially from Bangladesh and India. However, it was in 1990s microfinance took off the ground with the introduction of microfinance services to low income economically active people by non-governmental, public and private organisations in Sri Lanka.

The microfinance sector in Sri Lanka consists of a diverse range of institutions and does not fall under the purview of a single authority and there is currently no single and up-to-date database on these institutions. In this respect, the countrywide survey of MFIs in Sri Lanka commissioned by Thrift and Credit Co-operative Societies (TCCS) through a program titled ‘Promotion of Microfinance Sector’ (GTZ-ProMiS) during the programming phase September 2005 to November 2009, is worth mentioning.

The survey studied microfinance providers of various institutional types, from the village banks, cooperative rural banks, and thrift and credit cooperatives to the regional development banks and other institutions from the ‘formal’ growing financial sector who have ventured into microfinance. The survey also covered the rapidly growing NGO-MFIs some of which have grown very rapidly in the past decade.

The results of the survey indicate that the outreach of microfinance services in Sri Lanka is considerable, especially so concerning savings and deposit products. However, it reveals that access to credit remains below its potential and barriers still exist for the lower-income groups. Further, the market seems to be characterised by traditional financial products (savings, loans) with few products and services beyond these (e.g. insurance, money transfer services).

The challenges and opportunities

The growth of the sector is hampered by the lack of a coherent regulatory and supervisory framework, governance issues, lack of technology, and issues related to the availability of suitable human resources. Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) play a key role in generating employment facilitating growth in income and poverty alleviation of any country irrespective of its’ level of development.

According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the SME sector accounts for 90% of all firms in developed and developing countries. Further, the contribution of the sector to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of developing countries is particularly important as these countries experience high levels of unemployment, poverty, and highly skewed income distributions. Specific data about micro-enterprises by the government institutions such as Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) and the Department of Census and Statistics (DCS) are not available and these organisations consider micro-enterprises within the SMEs.

According to the findings of studies conducted in countries such as Bangladesh, India, China, Kenya, Tanzania, Sri Lanka, and many others, microfinance can be considered as a tool for the alleviation of poverty, among low-income categories of the society and especially the women.

The microfinance services are offered by focusing on women by the microfinance institutions in Sri Lanka like in many other countries. Further, 22.6% of the population lives in households headed by females in Sri Lanka according to the Department of Census and Statistics (1917). Therefore women achieving entrepreneurial success through microfinance services is important in many ways, especially in the context that there are diverse views presented by the scholars on the effectiveness of microfinance in achieving entrepreneurial success.

The women in Sri Lanka are faced with many challenges resulting in the poor well-being of themselves and their children. Hence, their achieving entrepreneurial success is important for them, their families, and the economy in general. Out of the total ‘economically inactive population’ of the country, 75% are females, and out of the total ‘economically active population’ (labour force) females account for only 36% (Department of Census and Statistics, 2015).

This implies that there is a large untapped female population in the country, which could be utilised for the development of the country. Given the fact that the majority of the population is women in Sri Lanka, attracting them to the labor force is of utmost importance.

Increasing female labor force participation can be done in two ways; firstly, by attracting women to the labor force as ‘employees’ and secondly by encouraging women to act as ‘employers’. The women who obtain microfinance services fall into two categories, those who already operate their enterprises and others planning to start new enterprises.

In studies conducted both in Sri Lanka and abroad, a positive relationship between microfinance and expansion of existing enterprises has been established. The most immediate impact, the MFIs have observed in their clients are the economic benefits such as an increase in income, expenditure, and assets of client households.

Current situation of microfinance

The preliminary study conducted by the author about the microfinance sector shows that the Non-Bank Financial Institutions (NBFIs) registered with the Central Bank are following the financial systems approach in delivering microfinance services whilst other providers of microfinance services appear to have a mixed approach.

Especially some of the NGOs operating in the market follow a non-commercial orientation to their business and donate funds to overcome extreme poverty situations, which is admirable. However, NBFIs are catering to the major portion of the microfinance market by value of loans. Further, microfinance clients are being serviced by so many other institutions and individual lenders at present according to the information available, the number of these service providers are as high as 11,000 or more.

According to the Central Bank, there are more than 40 NBIFs registered with the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, and of which, about 10 NBFIs have a major share of their portfolios in microfinance. Further, these large numbers of small scale lending institutions, NGOs, and private operators offering microfinance in the country, and these lending institutions fall into four major categories.

1) Local, regional, and national level microfinance institutions, 2) Village banks, 3) Cooperative rural banks and 4) Development banks. These institutions follow microfinance models falling into one of the models such as village banking, Grameen type, Individual lending using a group focus, individual lending, Self-Help Groups (SHGs), credit unions/cooperatives, and Rotating Savings and Credit Associations (ROSCAs).

The Lanka Microfinance Practitioners’ Association (LMPA) is a pioneer institution in microfinance networking among microfinance practitioners in Sri Lanka and was initiated on 31 March 2006. The Lanka Microfinance Practitioners’ Association is incorporated as a non-profit organisation under the Companies Act No. 7 of 2007.

Further, having observed the progress and importance of the microfinance sector, by Government authorities, the Government of Sri Lanka has passed a bill in the parliament to regulate the industry by the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, in 2016.

In 2018, LMPA introduced a Code of Conduct targeting microfinance practitioners to its members to avoid over-indebtedness, improve transparency, to facilitate loan disbursement and recovery practices, to maintain healthy competition, to develop a feedback mechanism, for better information sharing, and to improve quality of staff in keeping with LMFPAs mission.

However, the MFIs currently servicing the microfinance sector do not pay sufficient attention to the non-financial aspects of microfinance services such as skills development of clients, offering support to their business, and capacity building of clients. These MFIs are interested in offering loans and recovering such loans securely without upsetting the ‘apple cart’. They resort to the least risk approach in servicing their clients and recovering the loans on time and continuing their businesses earning high profits.

These MFIs are not concerned about the progress of their clients either in a business development aspect or in a social development aspect but only looking at short term profits to grow their – MFIs business. Hence these MFIs do not lend much support to their clients in their social and long term business development. As a result, women in the microfinance sector remain at a very basic stage not only in their micro-businesses but also as useful citizens in the country.

The capacity development of microfinance clients is one of the key roles in microfinance as the mere provision of loans may not facilitate the development of enterprises of these women belong to low-income categories and educational-social levels.

A survey conducted by the author in three districts; Gampaha, Amara, and Jaffna among 500 women receiving microfinance from MFIs in Sri Lanka revealed that 91% of the respondents in the sample had received education up to General Certificate of Education (GCE) while 7% and 1.5% had educational qualifications up to GCE Advanced Level and up to Degree level respectively. Their income levels are given in Table 1.

The most dominant age category of the respondents was 30-35 years with almost 26% falling into this category, however, age categories (25-30), (35-40), and (40-45) had percentages of more than 19%. Hence the age of almost 86% of the respondents was between 25 and 45 of the women in the sample who used microfinance services. These demographic statistics are explanatory enough to get a fair idea about the socio-economic status of women in the microfinance sector.

The data in the Table 2 show that the businesses that these women are engaged are very basic, only 25% of these women were engaged in manufacturing and garments all other businesses are of very basic types. The loans are obtained only by approximately 30% of the women for startups.

The way forward

No organisation either in the public sector or private sector possesses detailed current information about the sector hence the first step in the forward march is to get a clear understanding of the sector. To do this a comprehensive study at the level of a census should be conducted and gather all detailed and minute data about the microfinance suppliers, clients, demand, needs, and requirements of different stakeholders in the country.

This is a must in the absence of current data about the sector in the absence of any past comprehensive research in the field except for a few studies on specific research areas. It is needless to say that this magnitude of a study requires government sponsorship in a country like Sri Lanka. The following outcomes are expected from this study.

1. What is the real demand for microfinance and supply?

2. How many institutions and individuals are engaged in microfinance sector (stakeholders)?

3. What is the total number of clients? Are they satisfied with the services they receive?

4. What are the rates MFIs charge for their loans and interests offer to their clients for savings?

5. What are the weaknesses of offering capacity building programs and business assistance?

The next step is to formulate an actionable program based on the findings of the survey. This step too requires government backing and sponsorship. It is quite justifiable in the wake of COVID 19 for the government to embark on this initiative to mitigate the ill effect of post COVID-19 on the microfinance sector of Sri Lanka.

The contribution of the microfinance sector to the economy is a well-kept secret in the absence of reliable data. The number of clients in the microfinance sector according to industry practitioners would be around 2.5 million. In the absence of data, these can be considered as “gestimates” however this figure will reveal the magnitude of the problem.

There should be a Government-backed MFI that can chip in bridging any gaps in the sector such as the short supply of microfinance services and effective monitoring of the sector is also a must to develop a healthy competitive environment in the sector.

Most of the weaknesses of the microfinance sector such as exorbitant interest rates, putting poor into the debt trap, have occurred as a result of the absence of a proper regularity and monitoring institution in the country rather than shortcomings of microfinance as a strategy for entrepreneurial development of poor. The mere introduction of an act on microfinance is not at all a solution unless it is implemented. The Central Bank cannot be held responsible and is not in a position to implement an effective program in this respect.

Therefore there is a great need for establishing a professional level Microfinance Institution and Regulatory and Monitoring Authority by the Government if the real benefits from this strategy to be reaped in the future. I have never been an advocator of setting new institutions and power structures that could disturb the free market forces however this situation is exceptional considering the pros and cons given situation. This approach does not mean to disturb the existing large number of microfinance operators from individual lenders to an organised MFI but to bring in some order and discipline to the system to make microfinance work for developing the Sri Lankan economy addressing the poorest of the poor segment of our population.

This is a rare opportunity for the microfinance sector to step in and provide a professional service with a humane touch to the poor of our country. I believe that the Government would attach adequate attention and seriousness to the microfinance sector in the wake of the COVID pandemic as an effective strategy for the alleviation of poverty which has already been recognised by the United Nations long ago.

[The writer is a scholar who had conducted extensive research into the microfinance sector in Sri Lanka with hands-on experience in the sector for several years. His doctoral research on ‘Entrepreneurial Success of Women in Microfinance Sector’ has been published by one of the most reputed book publisher based in Germany. He belongs to a rare breed of academics who counts more than 40 years of exposure to the corporate sector both in private and public organisations holding top management positions including in leading trade chambers. He is currently a Senior Lecturer of the SLIIT Business School, Faculty of Business. He is a Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D. in Business Management) from the Management and Science University (MSU) of Malaysia. He also holds an MBA from the University of Colombo, Post Graduate Diploma in International Marketing from Colorado State University – USA, Bachelor of Science Degree (Mathematics and Statistics) from the University of Jaffna, and a Diploma in Computer Systems Design from CICC – Japan, among other qualifications.]